For true sustainability, organisations need to create value for all people connected to them. It’s not just a nice idea—it’s central to better outcomes for organisations and humanity.

We are operating in a human-powered economy. Organisations are at a watershed moment, with many having transitioned from an industrial economy to a knowledge economy and now to an economy that is powered by the hearts, minds, and essential human traits of people—in short, our humanity. Today, for many organisations, nothing is more important than its people, from workers and contractors to customers and community members. These human connections drive everything of value to an organisation, including revenue, innovation and intellectual property, efficiency, brand relevance, productivity, retention, adaptability, and risk. Yet organisations’ current efforts to prioritise these all-important connections are generally falling short—in part because many organisations are stuck in a legacy mindset that centers on extracting value from people rather than working with them to create a better future for organisations and individuals alike.

To advance on the social dimension of ESG (environmental, social, and governance), leaders should reorient their organisations’ perspective around the idea of human sustainability: the degree to which the organisation creates value for people as human beings, leaving them with greater health and well-being, stronger skills and greater employability, good jobs, opportunities for advancement, progress toward equity, increased belonging, and heightened connection to purpose.

Human sustainability—a concept we introduced in the 2023 Global Human Capital Trends report1—requires organisations to focus less on how much people benefit their organisation and more on how much their organisation benefits people. Some organisations are already making this shift. As Gabriel Sander, head of human resources for global distillery, Cuervo, said, “Companies can’t offer you employment forever, but they should make you employable forever.”

Companies can’t offer you employment forever, but they should make you employable forever.

Gabriel Sander, Cuervo

Redefining the “S” in ESG

Research shows that ESG is becoming increasingly unclear, unpopular, and polarising.2 Its attempt to encompass all facets of sustainability can make ESG both vague and an easy target for demagoguery—likely the reason organisations increasingly are avoiding it on earnings calls.3 While many countries in Europe are setting a high bar for ESG compliance, other countries are experiencing an ESG backlash, with investors pulling out of ESG funds entirely.4 And for some organisations, ESG may be considered more a means to an end, a framework of categories as a means for classification or reporting, rather than the end goal itself.

Organisations typically group interactions with people under the “S” component of their ESG efforts. That approach is limiting. “S” often lives in the shadow of “E.” Unlike environmental metrics like carbon emissions, which tend to be relatively straightforward to quantify, social metrics often lack clear definitions or standardisation: According to our 2024 Global Human Capital Trends research, only 19% of leaders say they have very reliable metrics for measuring the social component of ESG. And only 29% strongly agree that they have a clear understanding of how to achieve it.

In the absence of clear definition, organisations often take narrow or self-promotional approaches to measuring their human impact. Many focus just on short-term risks (for example, a public relations issue), undervaluing efforts that make a positive impact on society (for example, worker training or financial inclusion). Fundamentally, people-focused metrics tend to be rooted in an extractive, transactional mindset. For example, metrics that measure employee engagement in effect indicate how much discretionary effort workers are willing to expend for their organisation’s benefit. Is high employee engagement a good thing? It helps the organisation; whether it helps employees is less clear.

People and organisations are increasingly awakening to the idea that the earth is a complex, fragile system, not a bottomless set of resources, and that nurturing the planet is fundamental to building a better future for everyone. The move toward human sustainability represents a parallel shift in organisations’ concept of people. It requires a comprehensive effort by an organisation to add value for the individuals it affects across multiple dimensions, most notably those listed in figure 2. Human sustainability applies to all people in contact with the organisation: not just current workers, but also future workers, extended (contingent, gig, or external supply chain) workers, customers, investors, communities where the organisation operates, and society broadly.

But human sustainability isn’t just another name for stakeholder capitalism: simply delivering a wider range of outcomes for a wider range of stakeholders. Some suggest that, in the name of stakeholder capitalism, for example, organisations may make a positive contribution to a stakeholder group to balance out some of the adverse impacts to that group, much as carbon offsets function.5 These offsets can sometimes fail to address the root causes in the organisation, and the positive impact in one area does not necessarily compensate for the adverse impacts elsewhere. To balance various stakeholder interests, some say priority is often given to interests aligning with organisational objectives or of high importance to individuals with influence, often entrenching social inequities or resulting in organisations defaulting to meeting ESG regulatory requirements or reducing risk.6

A focus on stakeholders alone tends to obscure the fact that organisations rely on more than positive stakeholder relations for their long-term organisational success. Being a stakeholder-focused organisation is not the same as being a sustainable organisation whose success demands long-term, collaborative efforts to create shared value. An organisation is sustainable when it addresses the complex problems of the underlying structural and systemic issues that stand in the way of creating value for humans at the systems level. Creating another bolt-on program or employee benefit, such as gym memberships, meditation training, or volunteering time with the community, is not human sustainability. Achieving human sustainability isn’t easy, and often requires important trade-offs and careful balancing of short-term initiatives and longer-term practices that can address some of the root causes of difficult structural and systemic issues.

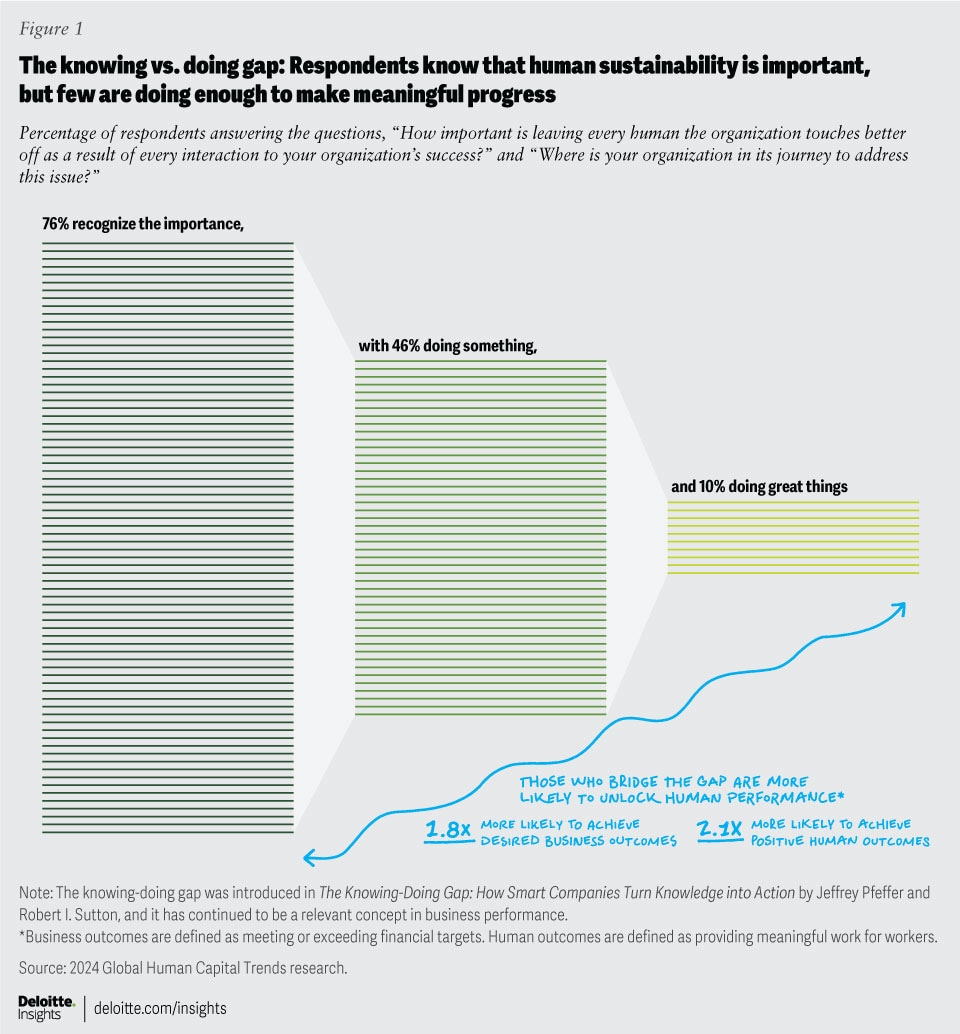

This approach is in its infancy today. Only 10% of organisations say they are leading in advancing human sustainability. Among those that are, efforts are likely to be fragmented and uncoordinated, pursued in isolation by disparate groups (for example, experiments with nondegree hiring, four-day work weeks, living wages, or employability improvement with skills passports).

Signals your organisation should prioritise human sustainability

- You’re struggling to make progress on social ESG goals, including objectives related to well-being, worker skills, and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

- You find ESG objectives vague, don’t have the right metrics, or don’t have a clear business case for the work.

- Your organisation is unsure how to handle the changing relationship with workers as they redefine the role work plays in their life.

- Your leaders are feeling pressure from workers, customers, board members, and other stakeholders around human issues.

- You’re experiencing more workforce-related risks, including increases in health and safety incidents and potential worker displacement by artificial intelligence.

Current Trends Threaten Human Sustainability

The worker-organisation relationship is becoming increasingly fraught amid broad disruptions in business and society.

Only 43% of workers say their organisations have left them better off than when they started.

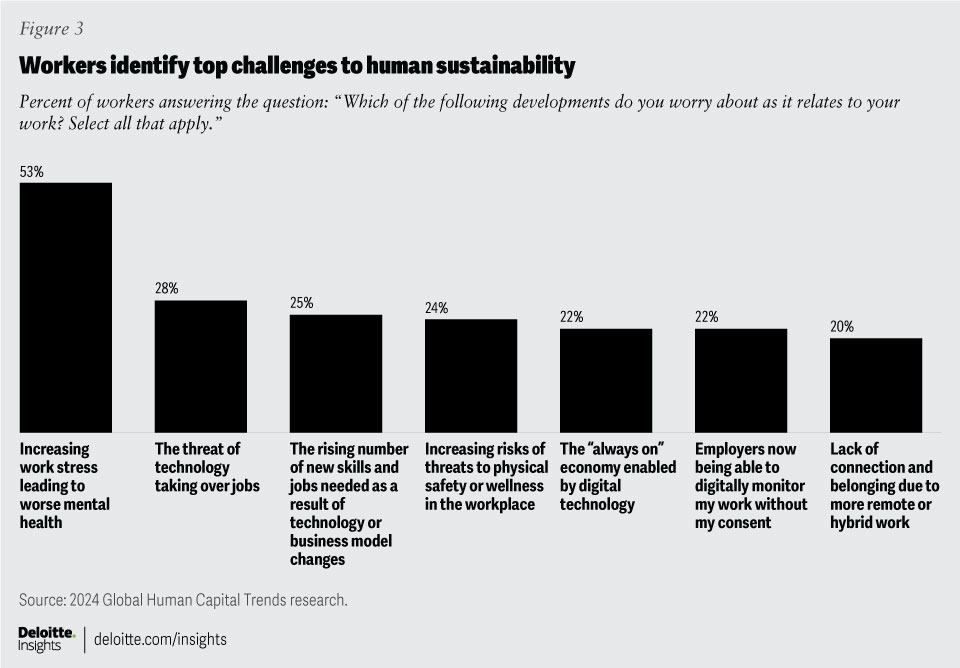

Only 43% of workers say their organisations have left them better off than when they started. In our research, workers identified increasing work stress and the threat of technology taking over jobs as the top challenges to organisations embracing human sustainability (figure 3).

There are also many developments in the world and in the workforce that threaten to leave people worse off. Some of them include:

- Rampant worker burnout: Constant change and overwork are taxing workers. Worker stress worldwide hit a record high for the second year in a row in 2022, with about half of workers “always” or “often” feeling exhausted or stressed.7 More than four in 10 report feeling burned out at work.8

- Concerns about AI eliminating jobs: According to a recent study, roughly two-thirds of workers in the United States and Europe will be impacted by generative AI, with generative AI substituting up to one-fourth of current work.9 The World Economic Forum estimates that generative AI could result in 83 million job losses globally over the next five years.10 Women workers are especially vulnerable: Men outnumber women in the workforce, but women are more likely than men to be exposed to the impact of AI.11

- Rapidly evolving skill needs: The half life of skills continues to shrink, with skills evolving at a rapid pace.12 Yet only 5% of executives strongly agree that their organisation is investing enough in helping people learn new skills to keep up with the changing world of work.13

- Support for gig and contract workers: Approximately 2 billion people globally are working informally (for example, contract work).14 These workers often do effectively the same work as their hired colleagues but may earn less and receive fewer benefits or protections.15

- Lack of visible progress on DEI: Although almost all HR leaders (97%) say their organisations have made changes that are improving DEI outcomes, only 37% of workers strongly agree that they’re making progress.16

- Poor conditions for frontline workers: Frontline workers compose about 80% of global workers,17 but research suggests they feel underserved by training, are less likely to have opportunities to work on purposeful projects, experience low wages, receive little paid time off, and are less likely to have health insurance.18

- Climate change and the energy transition affecting global workers: The Deloitte Economics Institute estimates that more than 800 million jobs worldwide—one quarter of the global workforce—are highly vulnerable to climate extremes that affect, for example, access to clean air and water, and the economic effects of the transition.19

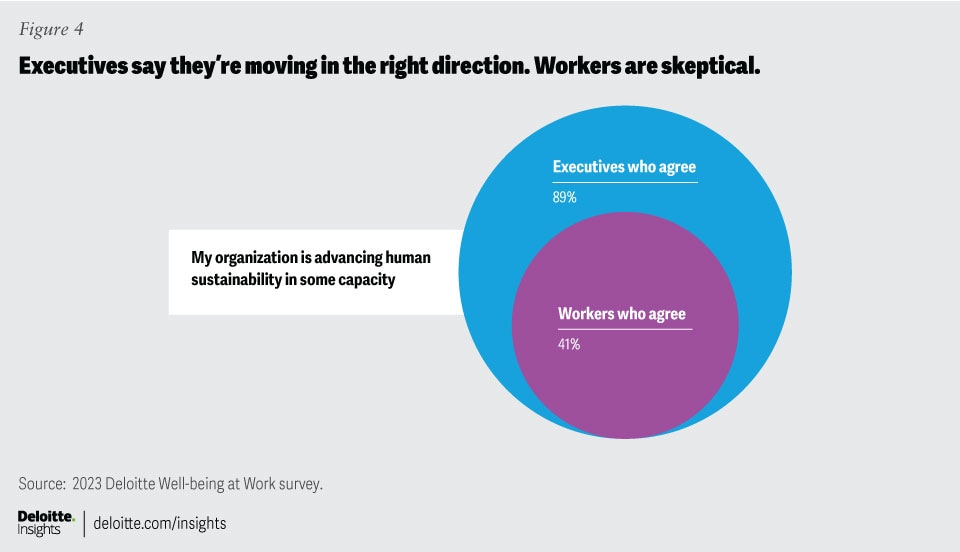

Executives are on board with the idea of human sustainability in theory: The large majority surveyed in the Deloitte Global skills-based organisation research (79%) say their organisation has a responsibility to create value for workers as human beings and for society,20 and 81% say human sustainability is very or critically important. But just 12% of executives say they’re leading in this area, while 17% say they have yet to make any progress. Meanwhile, only about a quarter of workers (27%) say their employer is making progress in creating value for them.21

An extractive approach to people, in which an organisation looks to maximise the immediate value it receives from people while minimising their cost, stands to exacerbate the trends above. It could lead organisations to use AI to eliminate jobs rather than create or improve them, resist rather than embrace the postcarbon transition, swell the ranks of gig workers with meager safety nets, fail to make the investments needed to move the dial on DEI, and burn out workers.

That said, many of these developments also offer enormous potential for both people and organisations. Human sustainability offers a key to harnessing them to build a better future.

When People Thrive, Business Thrives

Focusing on human sustainability can help organisations create beneficial outcomes for people and for themselves.

A focus on human sustainability can help organisations develop even more robust measures than evolving government policies related to people issues, which typically lag behind the pace and necessary scope of change. Regulations—such as the US Human Capital Disclosure Rule, Japan’s recently instituted Amendment on Disclosure of Corporate Affairs, and the European Union’s new European Sustainability Reporting Standards—may be necessary, but not always sufficient.

While people can represent risks to an organisation, they also represent great opportunities. Consider that intangible assets—the ideas, technologies, brand attributes, and other differentiators created by an organisation’s people—made up 90% of US corporate assets in 2022.22 Intangible assets approached comparable levels in other developed markets, though they were lower in emerging markets.23

Studies have consistently found that organisations engaged in practices related to human sustainability produce stronger business results. Analysis by the University of Oxford Wellbeing Research Center finds a “strong positive relationship between employee well-being and firm performance,” including stronger profits and stock returns among organisations with the highest levels of well-being.24 In addition, organisations that rank the highest on addressing human sustainability issues consistently outperform the Russell 1000.25

In fact, the organisations that score highest on treatment of their workforce had a 2.2% higher five-year return on equity, emit 50% less CO2 per dollar of revenue, and are more than twice as likely to pay a family-sustaining living wage.26

A number of factors could help explain a connection between human sustainability and improved organisational value:

- A focus on human sustainability may help organisations receive the benefits of greater diversity, equity, and inclusion. Organisations with greater diversity are 2.4 times more likely to outperform competitors financially.27

- Organisations that invest in skills development have better business results. Eighty-four percent of workers at high-performing organisations say they receive the training they need to do their jobs well.28

- Pinching pennies on the workforce often backfires. Low wages often lead to higher turnover, lost sales, low productivity, weak attendance, low levels of innovation, poor execution, mistakes, and frustration among customers and managers.29

- Improving worker health and well-being can reduce workforce risk. A majority of workers say that improving their health is more important than advancing their career and that they are seriously considering quitting for a job that better supports their well-being.30

- Consumers are more likely to support socially responsible organisations. Three-quarters (76%) of consumers say they’re more likely to buy from organisations that are socially responsible.31

For these reasons and others, a human sustainability agenda can help future-proof organisations: bolstering their ability to access, engage and develop a diverse workforce; develop a strong, diverse pipeline of talent; become more rewarding and productive places to work; inoculate against a variety of risks; and appeal to consumers.

How Leaders Can Advance Human Sustainability

To embrace human sustainability, an organisation should first reset the way it views relationships with people.

A human sustainability mindset replaces extractive, transactional thinking about people with a focus on creating greater value for each person connected to the organisation.

A human sustainability mindset replaces extractive, transactional thinking about people with a focus on creating greater value for each person connected to the organisation. This shift can set the stage for leaders to implement broader actions in support of a human sustainability agenda using trust as the critical glue.

Consider starting with the following actions:

- Focus on metrics that measure human outcomes. Organisations often design people metrics either to quantify worker outputs and activities or as a box-checking exercise, rather than as an assessment of progress on outcomes and impact. For example, nearly a quarter (23%) of organisations measure progress on diversity commitments based on adherence to compliance standards.32

Consider measuring factors like the ones highlighted below that the organisation can act on to create a better future for both people and the organisation, and which include workers like external supply chain or contract workers in the analysis.

Skills development metrics can indicate the value an organisation is providing to its workers, extended workers, and future workers.

- AI-driven analysis of how quickly people are learning new skills

- Impact of skills and learning on worker outcomes such as promotions, individual performance, and employability

- Impact of skills and learning on organisational outcomes such as sales and customer satisfaction

- Percentage of workers displaced by disruptions such as AI who are reskilled and attain “good jobs”

Well-being metrics should include emotional, mental, physical, social, and financial well-being.33

- AI-driven sentiment analysis, survey, and interview results

- Work-related emails sent during off hours

- Health equity and trends associated with medical claims over time

- Physical, emotional, and mental well-being and safety data from wearables and neurotechnology, used with people’s permission

- Data on shifts or working time (for example, paid time off use, overtime) collected by sensors, email, chat, and calendars34

Purpose metrics measure the degree to which people feel their lives have meaning and they are making a positive difference in the world and their work.

- Surveys and pulse checks gauging individuals’ perceptions of purpose and meaning

- AI-driven analysis of worker motivations and sentiment35

- AI-driven analysis of time spent on meaningful, value-added work versus repetitive, nonmeaningful work

- Volunteering or social impact involvement based on participation levels or percentage of time spent

- Factors correlating with purpose (positively or negatively), such as worker sick leave, turnover rates, performance, and profitability36

DEI metrics measure the extent to which workers experience equity and belonging as a result of diversity, inclusion, and addressing the root causes of inequity in the workplace.

- Pay equity analyses

- Root cause analysis of identified workforce inequities

- Organisational network analysis measuring the effectiveness of equity interventions (for example, by measuring belonging and diversity in organization networks)

- Equitable outcomes for various worker groups on dimensions such as promotions to leadership, internal mobility, and retirement savings participation

Metrics around career stability and advancement can be indicators of how well an organisation fosters economic mobility and advancement for workers.37

- Percentage of people hired based on skills rather than degrees

- Average time it takes to move up one level (velocity of growth)

- Percentage of senior management promoted from within the organisation

- Career stability based on retention and wage measures

Societal impact metrics measure an organisation’s contribution to communities and the world at large.

- Economic empowerment produced, as measured, for example, by income generation, wage increases, job creation, and entrepreneurship opportunities

- Impact on skills and employability

- Impact on community health and well-being based on health care access, disease prevention, happiness, climate sustainability, and other measures

- Impact on social innovation and collaboration, as measured, for example, by number of public-private partnerships formed, new ideas generated, and knowledge shared within the community

- Make the business case for human sustainability. Making the mindset shift toward human sustainability often requires that leaders, executives, and board members have a clear picture of the business advantages of making this shift. Organisations may in fact be taking many steps toward human sustainability, but in a siloed or disconnected way. Connecting the dots between initiatives can help provide a holistic picture of the business impact of human sustainability.

As discussed above, a number of factors can demonstrate the benefits, and driving this change may mean creating models, pilot initiatives, and new metrics that focus on these factors. When PayPal, for example, began an initiative to improve the financial well-being of its entry-level and frontline workers, it needed to justify the additional costs from both a business and human perspective. The organisation estimated that for every one percent reduction in attrition, it would save US$500,000 a year from reduced recruiting, onboarding, and training costs and through improved productivity (read the full case study below).

- Tie leader and manager rewards to human sustainability metrics. To make progress on anything, an organisation needs to hold leaders accountable. Organisations should set goals to advance on key human sustainability outcome metrics and drivers and attach incentives to achieving them.

Many organisations are already taking steps in this direction. Almost three-quarters of S&P 500 organisations now connect executive compensation to sustainability metrics.38 Genpact, for example, uses a suite of internal tech tools, including its AI chatbot, to check in regularly with workers and learn what is or isn’t working well for them and to gauge their mood and sentiment. The tools aggregate a workforce “mood score” that is linked to 10% of bonuses for the organisation’s top 150 leaders, including its CEO.39 Mastercard takes this a step further, determining bonuses for all workers in part based on the organisation’s performance on carbon neutrality, financial inclusion, and gender pay parity.40 That said, there appears to be a long way to go. Less than half of our survey respondents told us their organisation holds itself and leaders accountable for the holistic well-being of its workers.

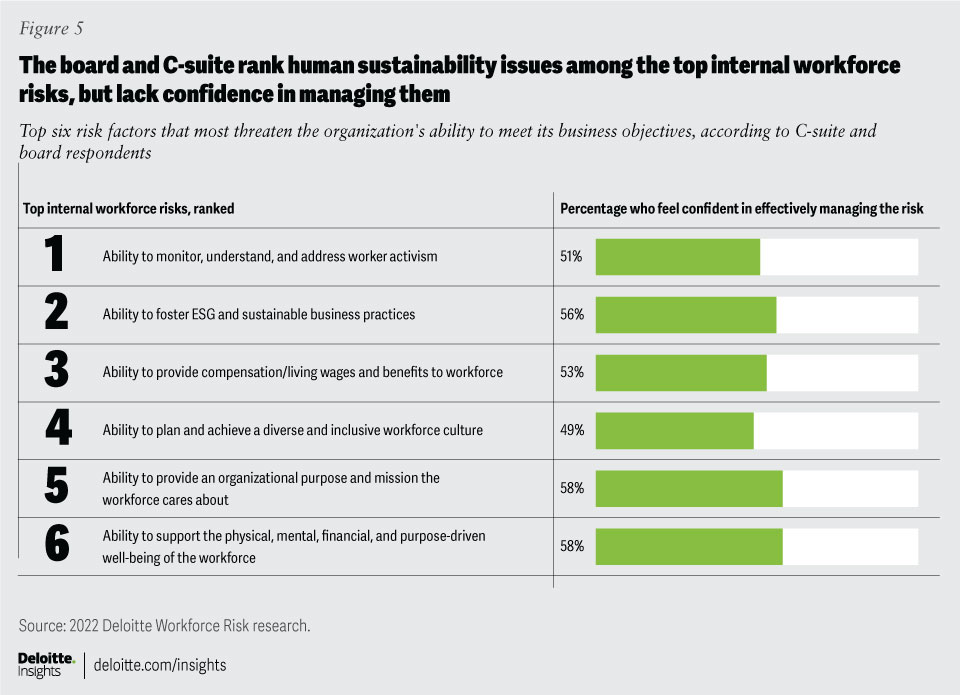

- Integrate human sustainability governance into the board and C-suite. Human sustainability is increasingly taking center stage on the boardroom agenda, as the board provides oversight on the intersection of strategy, risk, culture, and ESG and its relationship to business results. “We’re seeing increasing discussion at the board level of topics like DEI and ESG—and topics like changing workforce expectations, purpose, and skills now matter at the board level,” said Larry Quinlan, board member of six organisations. In one Deloitte US study, board members and C-suite leaders ranked human sustainability issues among the top internal workforce risks, yet many don’t feel confident in their ability to manage them (figure 5).41

While the board can provide oversight, ultimately, it is the C-suite’s responsibility to operationalise human sustainability and ensure all parts of the organisation are actively working to help humans thrive. The vast majority of C-level executives (95%) agree that executives should be responsible for worker well-being, a leading indicator of effective human sustainability efforts.42 But living up to that responsibility can require thoughtful, cross-functional governance at the highest levels.

People-related issues traditionally have fallen under HR. But managing human sustainability crosses almost all parts of an organisation, including finance, information technology, and operations, so HR can’t do the job on its own. Organisations should embrace a boundaryless HR approach that orchestrates the pursuit of human sustainability across disciplines to achieve it. They might also consider appointing a chief human sustainability officer to connect the dots between functions or create new roles in charge of key aspects of human sustainability, such as work redesigner, steward of purpose, or upskilling advocate.

- Involve workers, future workers, and others in cocreating their roles and human sustainability initiatives. To create value for individuals, organisations need input from individuals. Leaders can engage workers, future workers, contingent workers, community members, and other members of the organisation’s human ecosystem in dialogue about what they value and how it can be pursued together.

While these discussions may take shape in many ways, one important thread may center around reimagining workers’ roles—for example, integrating well-being into work design, building roles around purpose, or giving workers the freedom and autonomy to define “how” their work gets done. Consider tomato processor Morning Star, where each worker drafts their own outcomes and problems to be solved. For example, one worker’s personal mission is to turn tomatoes into juice in a way that is highly efficient and environmentally responsible. The statement then describes how they will work to achieve the objectives, including whom they will collaborate with and what decision responsibilities they will have.43

Approaches like this can create autonomy, continual learning and development in the flow of work, and the cultivation of human capabilities like imagination and curiosity used to identify problems and opportunities and then develop, test, and iterate on solutions.

Alternatively, worker roles may become more fluid through matching their skills, human capabilities, and unique motivations and passions to a portfolio of ever-evolving projects and assignments—unleashing greater agility, DEI, and greater growth, agency, and choice for workers.44 Both approaches rethink work by negotiating what and how it is done with the workers themselves.

- Elevate managers’ human sustainability role and empower them to own it. Managers can play a crucial role in advancing human sustainability, as they are the frontline leadership helping workers develop skills and creating psychological safety and belonging in teams. In one study, six in 10 workers worldwide said their job is the biggest factor influencing their mental health. The same study revealed that managers have as great an impact on a worker’s mental health as their spouse, and a greater impact than their doctor or therapist. Roughly seven in 10 said they would like their organisation and managers to do more to support their mental health.45 Organisations should empower managers with training, resources, and the autonomy to align policies and workloads with human sustainability priorities. In addition, ensuring managers have a clear window into human sustainability metrics can enable them to help the organisation achieve its commitments.

- Learn from leading organisations’ workplace practices. Organisations in the forefront of human sustainability are implementing initiatives—and in some cases, rewiring organisational practices—to add greater value for workers and society. Consider the following practices adopted by some organisations as they work toward embracing human sustainability:

- AT&T: Fewer than 5% of job openings require college degrees. In addition, the organisation trains heavily and recruits top managers from its own ranks—including CEO John Stankey, who does have a college degree and started his career at AT&T taking customer requests for phone service.46

- Zurich Insurance Group: People analytics assess workers’ current skills and future skill requirements, and technology curates learning and development opportunities. Capability network mapping helps identify areas where the organisation has networks of particular skills and capabilities and suggests ways for workers to strengthen their networks.47

Chobani: Workers in its plants have an average tenure of six years, longer than industry average. This could be due to the organisation’s emphasis on hiring refugees and offering ESL classes, language programs for managers, a child-care stipend, and relatively high starting wages.48 - Unilever: Unilever’s U-Work program offers temporary workers who contract with the company for a series of short-term engagements a guaranteed minimum retainer, access to organisational resources, and a core set of benefits like modified health care and retirement funding.49

- Hitachi: An executive sustainability committee tackles 11 goals that pose the most important social challenges for Hitachi, including quality education, gender equality, work and economic growth, health and well-being, and clean water and sanitation.50 One initiative seeks to prevent long working hours and overwork with a system that senses hours worked by each individual and then sends alerts to supervisors with suggestions on how to help coach overworked workers, as well as nudges to workers that encourage behavioral changes.51

In 2015, PayPal embarked on a new public mission: using technology to democratise financial services and improve financial health. That mission became personal in 2018 when the organisation assessed the financial wellness of its own entry-level and frontline workers and discovered that many were struggling financially. Approximately two-thirds reported living paycheck to paycheck, and the company estimated that net disposable income (discretionary income remaining after taxes and expenses are paid52) was as low as around 5%, even though the organisation was paying at or above market rates.53

Understanding that financial wellness is inseparable from physical, mental, and emotional wellness, PayPal launched a comprehensive program in 2019 to improve workers’ financial health. The initiative included reducing healthcare costs, granting stock awards to all workers regardless of level or tenure, raising wages where appropriate, and providing access to personal financial education resources.54 The organisation went on to allow workers to vest their stock awards more quickly and to provide earned wage access before the official pay period.55

Finding ways to address workers’ financial needs without putting the organisation under financial strain was a challenge, given the tens of millions of dollars the program would require in the first year alone. But leadership took a long-term view, agreeing that not only was it the right thing to do for workers, but it made good business sense. For every one-percent reduction in attrition, the organisation estimated it would save US$500,000 a year from reduced recruiting, onboarding, and training costs and through improved productivity.56

Today, PayPal has raised workers’ estimated net disposable income to 26% globally, with far less worker financial stress and absenteeism.57 The organisation is seeing higher capacity to meet customer needs and innovate, as well as all-time highs in employee engagement scores, productivity, and retention, and in net-promoter scores among customers.58

PayPal is continuing its mission by taking a lead role in advocating for financial well-being to be included as an urgent human sustainability agenda for every C-suite and board. “When you add up the impact on workers across different employers, you can very quickly get to big numbers that ripple throughout families, the economy, and communities,” said Tyler Spalding, PayPal’s senior director of corporate affairs and global head of social innovation.

Putting the Human in Sustainability

Human sustainability is a long-term play: The strategies put in place today will help determine whether workers, organisations, and society endure and flourish both today and for future generations. It’s a path toward creating a better future for us all, underscoring the interconnection between everything we do and need as humans, including climate sustainability, equity, trust, purpose, well-being, and belonging. And it calls on leaders and organisations to reflect—and act—on the role they play as stewards of human thriving, making a commitment to prioritise, measure, and improve human outcomes within their spheres of influence.

This work won’t happen overnight. The task is complex and will evolve constantly as the world changes. Organisations will need to take the lead and should also consider working together as part of coalitions to define best practices, standardise metrics, and push for smart policies. It will require challenging fundamental assumptions about business and its relationship with individuals and society—for example, some are suggesting the revision of accounting rules that currently treat people primarily as a cost.59 But it can be done: Our research indicates that the major challenge to progress on human sustainability efforts is internal constraints and that few respondents say they have sufficient resources.

A human sustainability perspective is grounded in a few simple principles: The people connected to your organisation have the power to affect it in important ways. Your organisation has the power to affect each of them. And by understanding and creating value for each other, your organisation and its people can improve business, work, and life for everyone.

Research Methodology

Deloitte’s 2024 Global Human Capital Trends survey polled 14,000 business and human resources leaders across many industries and sectors in 95 countries. In addition to the broad, global survey that provides the foundational data for the Global Human Capital Trends report, Deloitte supplemented its research this year with worker- and executive-specific surveys to represent the workforce perspective and uncover where there may be gaps between leader perception and worker realities. The executive survey was done in collaboration with Oxford Economics to survey 1,000 global executives and board leaders in order to understand their perspectives on emerging human capital issues. The survey data is complemented by over a dozen interviews with executives from some of today’s leading organisations. These insights helped shape the trends in this report.

- Sue Cantrell, Karen Cunningham, Laura Richards, Kraig Eaton, David Mallon, Nic Scoble-Williams, Michael Griffiths, John Forsythe, and Steve Hatfield, Advancing the human element of sustainability, Deloitte Insights, January 9, 2023. View in Article

- Alan Murray and David Meyer, “‘ESG’ represents a fundamental shift in business strategy—but the term is unclear, unpopular, and increasingly polarizing,” Fortune, July 21, 2022. View in Article

- John Butters, “Lowest number of S&P 500 companies citing “ESG” on earnings calls since Q2 2020,” FactSet, June 12, 2023. View in Article

- Nicole Goodkind, “ESG has lost its meaning. One advocate says let’s throw it in the trash,” CNN Business, October 3, 2023; Tommy Wilkes and Patturaja Murugaboopathy, “ESG equity funds suffer big outflows, buffeted by market jitters and US backlash,” Reuters, July 6, 2023. View in Article

- Rachel Dekker, “Why stakeholder capitalism is not enough,” Embedding Project, October 5, 2021. View in Article

- Ibid. View in Article

- Gallup, State of the global workplace: 2023 report, accessed December 2023. View in Article

- Future Forum, Future Forum Pulse, February 2023. View in Article

- Joseph Briggs and Devesh Kodnani, The potentially large effects of artificial intelligence on economic growth, Goldman Sachs, March 26, 2023. View in Article

- World Economic Forum, Future of jobs report 2023, May 2023. View in Article

- Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise, “Will generative AI disproportionately affect the jobs of women?,” April 18, 2023. View in Article

- Jorge Tamayo, Leila Doumi, Sagar Goel, Orsolya Kovács-Ondrejkovic, and Raffaella Sadun, “Reskilling in the age of AI,” Harvard Business Review, September–October 2023. View in Article

- Michael Griffiths and Robin Jones, “The skills-based organization,” Deloitte, November 2, 2022. View in Article

- Kunal Sen, “Over 2 billion workers globally are informal—what should we do about it?,” United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research, May 2021. View in Article

- World Economic Forum, The Good Work Framework: A new business agenda for the future of work, May 17, 2022; Catherine Bracy, “A more ethical approach to employing contractors,” Harvard Business Review, August 2, 2023. View in Article

- Jeremie Brecheisen, “Where companies think companies diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging efforts are failing,” Harvard Business Review, March 9, 2023. View in Article

- Microsoft, Work Trend Index special report: Technology can help unlock a new future for frontline workers, January 12, 2022. View in Article

- Microsoft, Will AI fix work? (2023 Work Trend Index: Annual report), May 9, 2023; Ed Frauenheim, “Purpose at work: Soaring over gaps with incredible company culture,” Great Place to Work, June 2, 2022; Naina Dhingra, Andrew Samo, Bill Schaninger, and Matt Schrimper, “Help your employees find purpose—or watch them leave,” McKinsey & Company, April 5, 2021; Matt Gonzales, “The plight of frontline workers,” Society for Human Resource Management, January 14, 2023. View in Article

- Pradeep Philip, Claire Ibrahim, and Emily Hayward, Work toward net-zero, Deloitte, November 2022. View in Article

- Griffiths and Jones, “The skills-based organization.” View in Article

- Ibid. View in Article

- Brand Finance, Global Intangible Finance Tracking™ 2022, November 2022. View in Article

- Ibid. View in Article

- University of Oxford WellBeing Research Center, “Homepage,” accessed December 2023. View in Article

- JUST Capital, “Index concepts,” accessed December 2023. View in Article

- Ibid. View in Article

- Development Dimensions International, Inc., Diversity, equity, and inclusion report 2023, accessed December 2023. View in Article

- IBM, The value of training, accessed December 2023. View in Article

- Ton, The Case for Good Jobs. View in Article

- Steve Hatfield, Jen Fisher, and Paul H. Silverglate, The C-suite’s role in well-being, Deloitte Insights, June 22, 2022. View in Article

- World Economic Forum, The Good Work Framework. View in Article

- Christina Brodzik, Joanne Stephane, Devon Dickau, Nic Scoble-Williams, Yves Van Durme, Michael Griffiths, Kraig Eaton, Shannon Poynton, John Forsythe, and David Mallon, Taking bold action for equitable outcomes, Deloitte Insights, January 9, 2023. View in Article

- Colleen Bordeaux, Jen Fisher, and Anh Nguyen Phillips, Why reporting workplace well-being metrics is a good idea, Deloitte Insights, June 21, 2022. View in Article

- Pamela B. de Cordova, Michelle A. Bradford, and Patricia W. Stone, “Increased errors and decreased performance at night: A systematic review of the evidence concerning shift work and quality,” Work 53, no. 4 (2016): pp. 825–834; Katharine R. Parkes, “Shift schedules on North Sea oil/gas installations: A systematic review of their impact on performance, safety, and health,” Safety Science 50, no. 7 (2012): pp. 1636–1651. View in Article

- Julie Lodge-Jarrett, “Ford’s employee sentiment strategy: Ask/listen/observe,” Institute for Corporate Productivity, April 1, 2020. View in Article

- Rhonda Evans and Tony Siesfeld, Measuring the business value of corporate social impact, Deloitte Insights, July 31, 2020. View in Article

- American Opportunity Index, “Homepage,” accessed December 2023. View in Article

- Ted Jarvis, Jamie McGough, and Donald Kalfen, “Incentives linked to ESG metrics among S&P 500 companies,” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, July 20, 2023. View in Article

- Amber Burton, “Genpact is using AI to flag employee dissatisfaction and tying leaders’ bonuses to the results,” Fortune, June 26, 2023. View in Article

- Michael Miebach, “Sharing accountability and success: Why we’re linking employee compensation to ESG goals,” Mastercard, April 19, 2022. View in Article

- Deloitte workforce risk survey of 875 different C-suite leaders, executives, and independent board members was conducted in winter 2021. For more on workforce risk, see: Joseph B. Fuller, Reem Janho, Michael Stephan, Carey Oven, Keri Calagna, George Fackler, Robin Jones, Sue Cantrell, and Zac Shaw, Managing workforce risk in an era of unpredictability and disruption, Deloitte Insights, February 24, 2023. View in Article

- Hatfield, Fisher, and Silverglate, The C-suite’s role in well-being. View in Article

- Susan Cantrell, “Beyond the job,” SHRM Executive Network, accessed December 2023. View in Article

- See, for example: Sue Cantrell, Karen Weisz, Michael Griffiths, Kraig Eaton, Shannon Poynton, Yves Van Durme, Nic Scoble-Williams, and Lauren Kirby, Navigating the end of jobs, Deloitte Insights, January 9, 2023; Cantrell, “Beyond the job”; Sue Cantrell, Michael Griffiths, Robin Jones, and Julie Hiipakka, The skills-based organization: A new operating model for work and the workforce, Deloitte Insights, September 8, 2022. View in Article

- UKG, “Mental health at work: Managers and money,” accessed December 2023. View in Article

- Lauren Weber and Theo Francis, “Want to get ahead? Pick the right company,” Wall Street Journal, October 14, 2022. View in Article

- David Green, “Taking a skills-based approach to workforce planning (interview with Ralf Buechsenschuss, Zurich Insurance Company),” myHRfuture, September 28, 2021. View in Article

- Amber Burton, “Chobani hired hundreds of refugees at its plants. Average tenure now exceeds industry average,” Fortune, July 7, 2023. View in Article

- Leena Nair, Nick Dalton, Patrick Hull, and William Kerr, “Use purpose to transform your workplace,” Harvard Business Review, March–April 2022. View in Article

- Hitachi, “Hitachi’s approach to sustainable development goals,” accessed December 2023. View in Article

- Hitachi, Hitachi sustainability report 2023, accessed December 2023, pp. 71–93. View in Article

- Ivy K. Lau-Schindewolf, “Research report: PayPal employee financial diaries,” PayPal, July 18, 2023. View in Article

- PayPal, PayPal employee financial diaries, accessed December 2023. View in Article

- Zeynep Ton and Sarah Kalloch, “PayPal and the financial wellness initiative,” MIT Sloan School of Management, November 8, 2022. View in Article

- PayPal, PayPal employee financial diaries. View in Article

- Ton and Kalloch, “PayPal and the financial wellness initiative.” View in Article

- Lau-Schindewolf, “Research report.” View in Article

- Tyler Spaulding (director of corporate affairs, PayPal) and Ivy Lau-Schindewolf (public affairs and strategic research lead manager, PayPal), online interviews with author, 2023. View in Article

- Peter Cappelli, “How a common accounting rule leads to more layoffs and less job training,” Wall Street Journal, July 28, 2023. View in Article

The authors would like to thank Gabriel Sander (Cuervo), Tyler Spalding (PayPal), Ivy Lau, and Larry Quinlan for their contributions to this chapter.

Deloitte’s DEI Institute contributed significantly to this chapter as well. Thank you to Sameen Affaf, Dr. Dhanushki Samaranayake, and Dr. Julian Sanders for their contributions.

In addition, we’d like to recognise the expertise of the following team members who contributed their insights and perspectives: Karen Cunningham, James Lewis, and Steve Hatfield.

Special thanks to Kristine Priemer for her leadership in the development of this content, and Bridget Acosta and Halle Teart for their contributions.

Cover image by: Sofia Sergi

The article was first published by Deloitte Insights.

Photo by Marc Mueller on Pexels.com.

5.0

5.0