INTRODUCTION

As a result of Section 211 of the 2016 Companies Act1, it is important boundaries are reset and documented between the roles and responsibilities of the Board and management. This is done in three parts: first, by the Board formulating strategy and providing accountability; second by achieving strategic alignment with the Board-determined Mission and Vision through the setting of strategy; third; defining clear boundaries of responsibility for directors and management, with appropriate supporting documentation in the Board Charter.

Formulating strategy and providing accountability

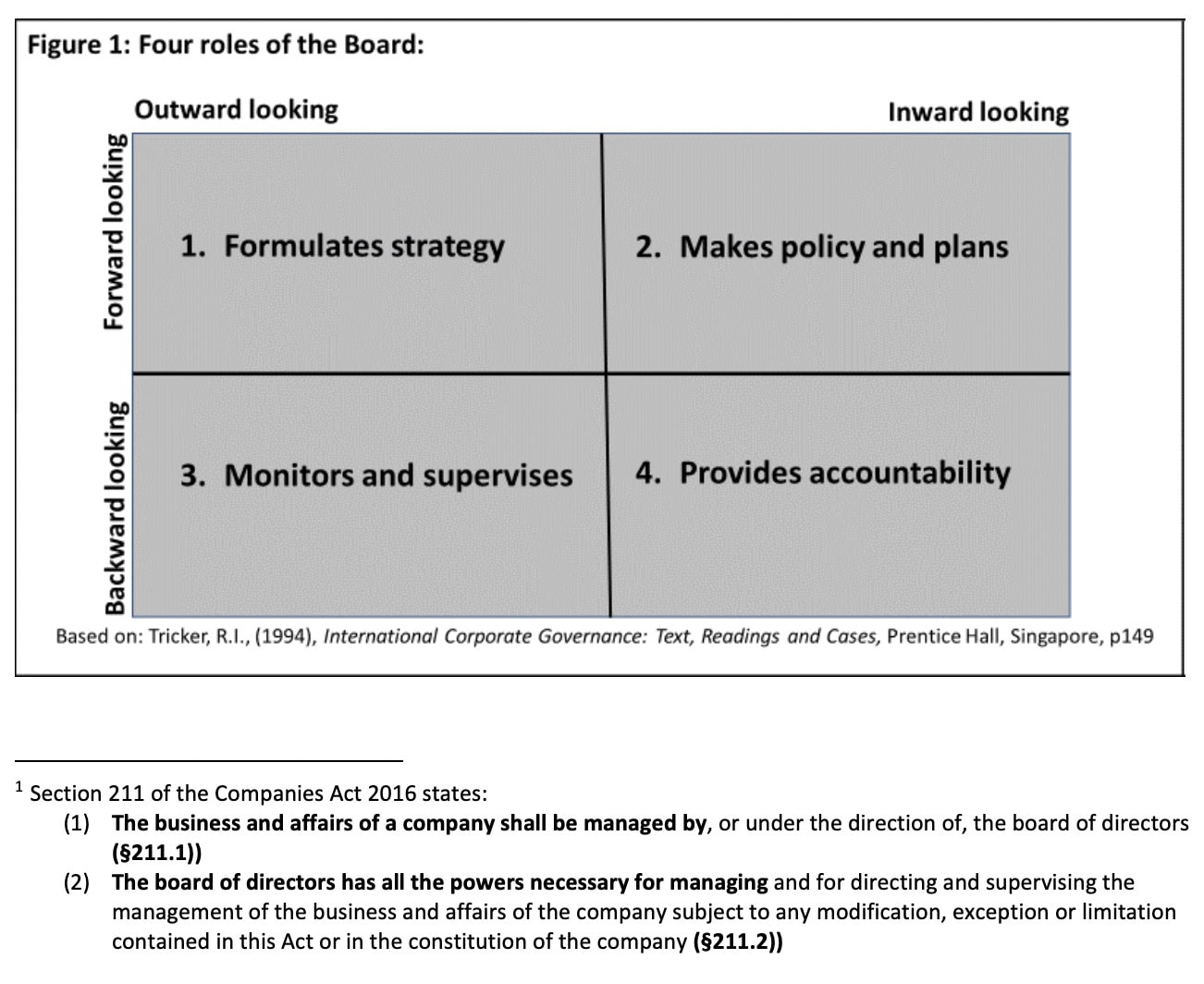

Figure 1 shows the role of the Board in formulating strategy and providing accountability through making policy and plans and monitoring performance, while management executes and the Board supervises execution:

In his pathbreaking analysis, Professor Bob Tricker, the so-called ‘grandfather of CG’, described the board as having four responsibilities: formulating strategy; making policy and plans; monitoring and supervising; and providing accountability. This is shown in Figure 1

Boxes 1 and 2 and are forward and outward looking, reflecting the role that boards ‘govern and direct’, boxes 3 and 4 are backward and inward looking, reflecting the role that boards oversee management and are held accountable for whatever happens on their watch.

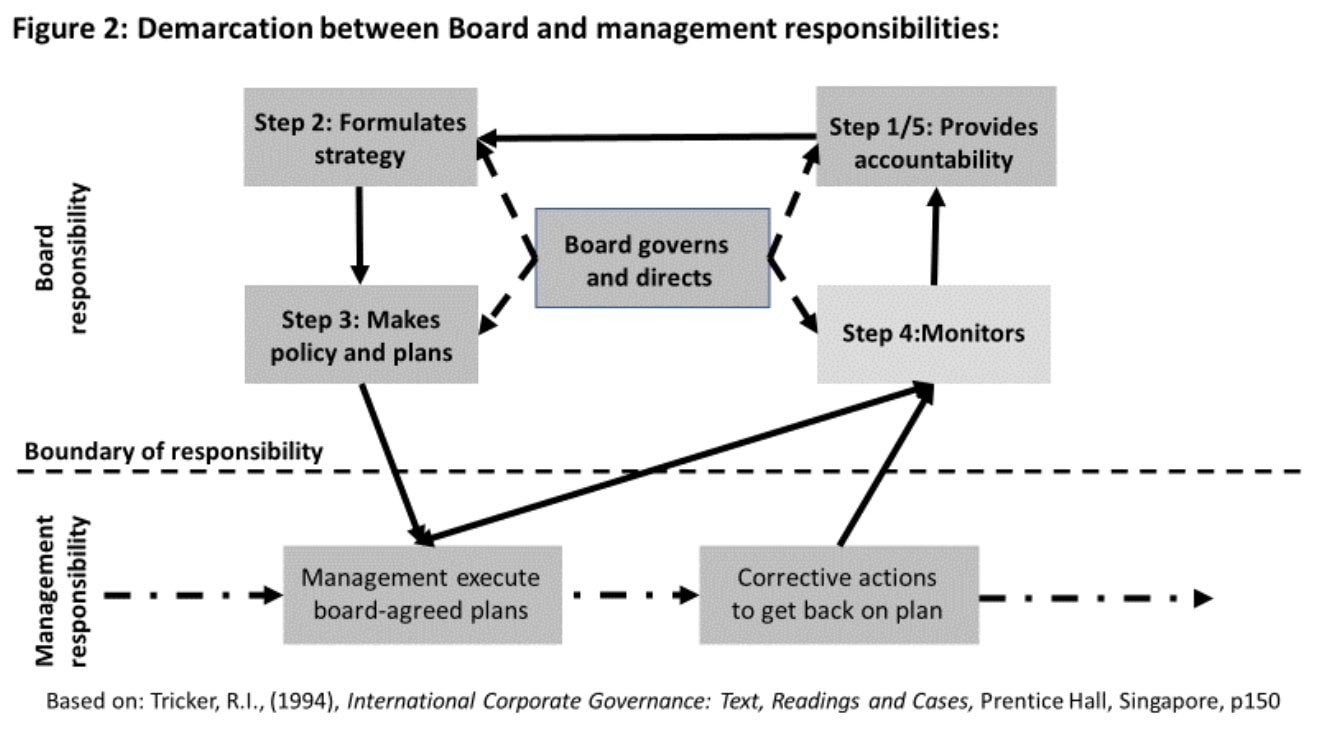

However, as figure 2 shows, Professor Tricker belonged to the school of thought that argues ‘boards govern and direct, management manages’2:

“The board of directors has the important role of overseeing management performance on behalf of shareholders…

[but] corporate directors are diligent monitors, but not managers, of business operations.”i

The board governs and directs in five steps: It provides accountability from the beginning (step 1), based on which the directors formulate the strategy (step 2) and its supporting policy and plans (step 3). These are then implemented by the CEO and the management team, and the board monitors performance (step 4), providing feedback to management who then take corrective action to get back on plan; the board continues to monitor (still step 4) and take accountability for any material variance from plan when answering to shareholders (step 5). Based on the outcome, they will then restart the cycle, with the reformulation of strategy based on what was or was not achieved. Indeed, nearly every code of Corporate Governance (CG) was based on the idea boards ‘govern and direct’ in this manner; and ‘managers manage’; and boards should not second-guess line management. Although the explanation below regarding the boundaries of responsibility was for NGOs, it applies equally well to for-profit organizations:

“Governance and management are not the same things. Governance is about vision and organizational direction as opposed to day-to-day management and implementation of policy and programs… In most civil society organizations, governance is provided by a board of directors, which may also be called the management committee, executive committee, board of governors, board of trustees, etc. This group oversees the organization, making sure it fulfills its mission, lives up to its values and remains viable for the future…Although by no means an exhaustive list, essentially, the board has the responsibility to:

Define expectations for the organization:

- Set and maintain vision, mission and values

- Develop strategy (e.g., long-term strategic plan)

- Create and/or approve the organization’s policies

Grant power:

- Select, manage and support the organization’s chief executive

Verify Performance:

- Ensure compliance with the governing document (e.g., charter)

- Ensure accountability and compliance with laws and regulations

- Maintain proper fiscal oversight

Management takes direction from the board and implements on a day-to-day basis. Management has the responsibility to:

Communicate expectations—mission, strategy, policies—to the entire staff;

Manage day-to-day operations and program implementation to fulfill the expectations; and

Report results to the board.

When the balance between the responsibilities of the board and management is established and functioning well, the organization is better able to:

Meet the expectations of clients, beneficiaries and other stakeholders;

- Deliver quality programs that are effective and efficient; and

- Comply with laws, regulations and other requirements.”ii

The failures of Enron in 2001 and WorldCom, Global Crossing, Tyco and Adelphia in 2002 in the US were the drivers of increasingly intense scrutiny of the board and its internal audit processes, as well as the role of external auditors, leading to the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002iii.

After the collapse of Enron, the US Business Roundtable in 2002 defined the responsibilities of the board as having the following primary oversight functionsiv:

Select, evaluate and if needed, replace the CEO. It should also plan succession and determine management compensation;

Review, approve and monitor operating plans, budgets, major strategies and plans, including assessing risk and continuity planning;

Ensure the integrity and clarity of financial statements and the independence of the appointed external auditors;

Provide advice and counsel to senior management;

Review and approve company actions;

Nominate a recommended slate of directors for shareholder approval;

Review the adequacy of systems to comply with all applicable laws and regulations.

No mention here of managing the business. In fact, it is still possible as late as 2005 for a director to conclude that boards ‘govern and direct, management manages’:

“In short, it is not the responsibility of the board to run the company. That is the job of management. Instead, directors have the difficult job of ensuring that those running the company run it as effectively as possible. Even before the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, there have been important discussions from many different quarters regarding how to build the most effective board of directors. The question is how best to structure a board to effectively exercise their responsibilities. The truth of the matter is that while a well-structured board will better enable more efficient oversight, it does not guarantee quality performance.”v

[Emphases mine]

While the UK Companies Act 2006 does not state that the board is responsible for running the company, it does encourage directors to adopt a proactive approach to CG, requiring INEDs to enquire into and gain an informed understanding of the conduct of the company. The standard to which they are now held is best illustrated by the words of Lord Goldsmith, the UK Attorney General, during the debate on the 2006 Companies Act:

“The duty does not prevent a director from relying on the advice of work of others, but the final judgment must be his responsibility… As with all advice, slavish reliance is not acceptable, and obtaining of outside advice does not absolve directors from exercising their judgment on the basis of such advice.”

In the Commonwealth, however, leading jurisdictions have taken a much more demanding view, stating categorically, in statute law, that directors are responsible for the management of the affairs of their companies, shown in Table 1:

Table 1: Directors are responsible for managing the company:

| Jurisdiction | What the law says | Relevant Act |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | The business of a company is to be managed by or under the direction of the directors. | Corporations Act 2001, section 198a |

| Canada | Duty to manage or supervise management 102 (1) Subject to any unanimous shareholder agreement, the directors shall manage, or supervise the management of, the business and affairs of a corporation. | Canadian Business Corporations Ac 1985, amended 2018, section 102 |

| Malaysia | The business and affairs of a company shall be managed by, or under the direction of, the board of directors (§211.1)) The board of directors has all the powers necessary for managing and for directing and supervising the management of the business and affairs of the company subject to any modification, exception or limitation contained in this Act or in the constitution of the company (§211.2)) |

Companies Act 2016, section 211 |

| New Zealand | 128 Management of company

The business and affairs of a company must be managed by, or under the direction or supervision of, the board of the company. |

Companies Act 1993, section 128 |

| South Africa | 66. (1) The business and affairs of a company must be managed by or under the direction of its board, which has the authority to exercise all of the powers and perform any of the functions of the company, except to the extent that this Act or the Memorandum of Incorporation provides otherwise.xi | Companies Act 2009, section 66 (1) |

The standard to which they are held in Australia and other Commonwealth countries where Australian rulings are regarded as either precedent or ‘persuasive’ is best illustrated by the words of Justice Middleton:

“Nothing that I decide in this case should indicate that directors are required to have infinite knowledge or ability. Directors are entitled to delegate to others the preparation of books and accounts and the carrying on of the day-to-day affairs of the company. What each director is expected to do is to take a diligent and intelligent interest in the information available to him or her, to understand that information, and apply an enquiring mind to the responsibilities placed upon him or her.”

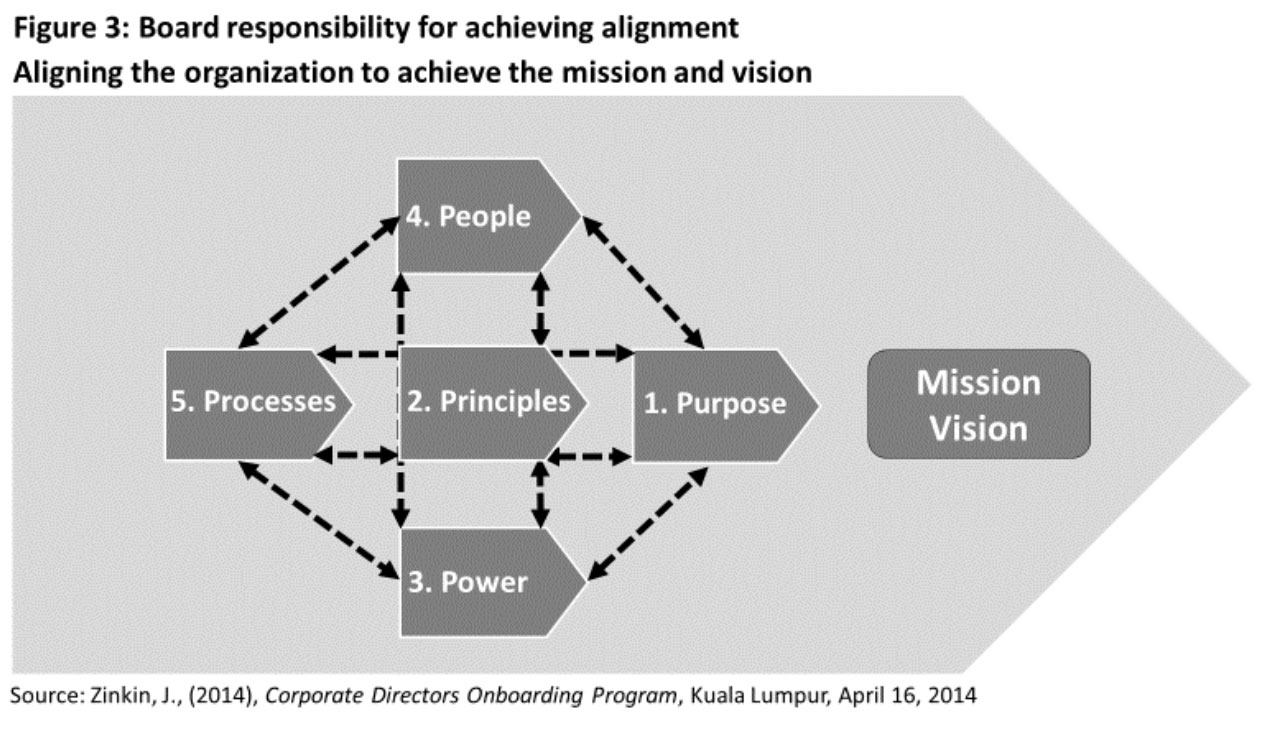

Achieving strategic alignment

Figure 3 shows how the Board-defined Mission and Vision (essential elements of effective strategy formulation) will only be achieved if the organisation’s ‘Five P’s’ are aligned properly. If any one of the ‘Five P’s” is misaligned and does not point towards the Mission and Vision, the Mission and Vision will not be achieved. This is because the ‘Five P’s’ interact with each other, either reinforcing or weakening the organisation’s ability to set priorities appropriately and allocate resources accordingly. Working together, they determine and reinforce acceptable behaviour and Values. Working separately, they will create inconsistent behaviour and undermine the Values of the organisation.

To do this, the Board is responsible for defining the strategic parameters, while management is responsible for operational execution for each of the ‘Five P’s’ as follows:

‘Purpose’: defining the businesses the company is in:

Board’s strategic responsibility:

Define values in terms of desired, observable, measurable behaviour

Establish standards for each category of behaviour applicable to all, including clear definitions of unacceptable behaviour

Management’s operational responsibility:

Set targets for individuals and review performance regularly as part of the appraisal process

Agree personal development plans with targets for improvement and agreed action plans as a result of appraisals

Follow up and take corrective action if needed. Enforce sanctions, as explained, when setting KPIs and targets

The Board is responsible for defining the organisational design needed to achieve the Mission and Vision. This includes reporting relationships and whether there is the ‘courage to speak truth to power’. Hence the term Power:

‘Power’: to support the Mission and Vision structurally:

Board’s strategic responsibility:

Specify organisation design and structure to meet agreed strategic objectives including resources needed and the timeline for completion

Establish and protect a culture in which constructive challenge from subordinates is welcome

Lay down standards for ‘speaking truth to power.

Management’s operational responsibility:

Establish formal criteria and reward mechanisms to encourage bringing up bad news early rather than ‘shooting the messenger’

Apply the same transparent standards regardless of position and seniority.

The Board then determines People needed to achieve the Mission and Vision. The Board must define not just the number of people needed to do the jobs determined by the organisation design and job evaluation exercises, but their competence and character as well:

‘People’: to get the jobs done ethically:

Board’s strategic responsibility:

Based on job evaluation studies, decide on the number and type of positions needed to fulfil current and future mission and vision

Review and update desired competencies

Develop succession plan and talent management strategy

Management’s operational responsibility:

Use succession planning and personal development plans to ensure positions are filled in a timely manner with people who have:

- Defined competencies to do the job

- Appropriate prior experience to step up

- Right character with integrity and courage to speak truth to power

Ensure the talent pipeline satisfies the changing needs of the organisation

Finally, the Board defines Processes – all operating systems, procedures and feedback mechanisms. They cover reward and appraisal systems, the setting and review of KPIs and scorecards, as well training and development schemes, and appropriate documentation of SOPS and SLAs:

‘Processes’: the glue that binds

Board’s strategic responsibility:

Ensure ‘Processes’ (policies, procedures and feedback mechanisms) support and enhance ‘Purpose’ (Mission, Vision) and ‘Principles’ (Values)

Agree ‘Processes’ recognising they affect the other four ‘Ps’ and are the glue that ensures organisational alignment to its mission and vision

Approve a written, trained and attested code of conduct

Ensure compliance mechanism is in place with confidential whistle-blowing procedures.

Management’s operational responsibility:

Develop SOPs and SLAs in line with Board-approved policies

Check for any misalignment with the Mission and Vision and amend accordingly

Check for non-compliance and take corrective action including enforcement

Redefining the Boundaries The real question then, is what does the law regard as ‘managing’? Whenever I have explained to directors the Malaysian Companies Act 2016 holds them responsible for managing the business, and that the words ‘managed by’ precede ‘or under the direction’, which means that a judge will look into their management practices as a priority, their reaction is one of shock. The majority signed up to become directors on the assumption that ‘boards govern and direct, management manages’. The issue becomes one of redefining where the boundaries of responsibility between board and management lie. Table 2 suggests how the six core responsibilities of the board divide into actions of the board and those of line management

Table 2: Redefining the boundaries of responsibility:

| Board’s Role | What the law says | Management’s Role |

|---|---|---|

| Sets strategy | TBoard as a whole:

Formulates strategy, policies and plans; Challenges management’s plan assumptions, priorities and options; Reviews the business plan and budget and sets targets for management. |

CEO and senior management:

Coordinate the development of business plan and budget across all BUs; Execute strategy and plans for company based on board-agreed direction and executive limitations; Report to the board on progress. |

| Reviews strategy implementation | Board as a whole:

Reviews, approves and provides feedback on corporate KPIs and targets; Reviews results quarterly, discusses material variances, and ensures corrective actions are taken if required; Follows up. |

CEO and senior management:

Establish corporate KPIs; Cascade KPIs throughout organisation; Monitor KPIs monthly with BUs, investigate variances and develop corrective actions if required; Report to the board on progress. |

| Manages risk | Board working through the AC or RMC:

Sets the company’s risk parameters; Understands major risk exposures and ensures appropriate risk mitigation approach is in place; Considers the risk factors in all major decisions. |

CEO and senior management:

Analyze and quantify the company’s risks; Manage all risks within the boundaries set by the board; Instill risk management culture throughout organisation; Implement ERM and COSO frameworks. |

| Plans succession | Board working through the NRC:

Selects and proactively plans CEO succession; Reviews the performance management philosophy; Evaluates CEO; Endorses the development plan of people in pivotal positions; Understands the pool of future leaders; Sets remuneration policies |

CEO, HR and senior management:

Develop and implement the company’s performance management system; Evaluate leadership performance and potential of all executives; Identify top talent pool and closely manage their performance and development plans; |

| Ensures internal controls | Board working through the AC:

Ensures through the appointment of an independent, experienced external auditor that the financial statements represent a ‘fair view’ of the business; Ensures IA have the resources and credibility to carry out appropriately scoped internal audit plan; Approves code of conduct and compliance processes applying to all employees and the board; Establishes an effective whistle-blower policy and confidential reporting channels to the AC; Ensures adoption of and adherence to COSO framework. |

CEO, CFO, CIO and Head of IA:

Ensure written SOPs, SLAs, policies and procedures are in place and reviewed regularly; Ensure IT systems support reporting and information needs correctly; Establish written code of conduct; Train employees regularly in code of conduct; Ensure code of conduct and compliance are being followed; Identify weaknesses and take corrective action; Enforce code of conduct and compliance; Report through IA to the AC on progress and any issues |

| Engages shareholders and stakeholders | Chair working with company secretary, corporate affairs, PR and investor relations:

Chairs general meetings (AGM and EGM) Ensures all shareholder views are represented and shareholders are treated equally; Balances and manages economic impact of stakeholder interests on shareholder value; Ensure all laws and regulations are followed correctly; Engage with the community to maximize social ‘licence to operate’ Supports management in handling key stakeholders. |

CEO and CFO:

Understand needs of shareholders and communicate key decisions in transparent manner to all employees; Ensure all disclosures or any other regulatory or statutory requirements are fulfilled; Manage all stakeholder interests within boundaries agreed with the board; Ensure company obeys environment, safety and health laws and regulations. |

The crucial point is not whether the demarcation above is absolutely correct, but that it, or whatever demarcation the company decides upon, must be documented in the board charter and or memorandum and articles of association. If this is done, should directors ever have the misfortune to be hauled up in front of a judge, they can show they fulfilled their responsibilities, as laid down by their company’s constitution, making it clear where their responsibilities end and management’s begin. If they can demonstrate they fulfilled their responsibilities within these boundaries, they will likely be covered by the ‘business judgment rule’ and prove they have not been negligent or of acting in bad faith.

References

2“The board should elect members who understand and respect the difference between governance and management. Choose wisely, seeking as directors individuals who bring no personal agendas, understand the role of management in large, complex organizations, and have a desire to work as part of the board-management team. Then conflicts between the board and management will be rare.” Bader, B. S., (2008), “Distinguishing Governance from Management”, http://trustees.aha.org/boardculture/archive/Great-Boards-fall-2008-reprint-distinguishing-governance-and-management.pdf, accessed on July 3, 2018

iBusiness Roundtable (2012), quoted by Useem, M., Carey, D., Charan, R., (2016), “Boards that lead” in The Handbook of Corporate Governance, edited by Leblanc, R., (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc), p42

iiFHI 360, USAID, Capable Partners Development Program (CAP), (2009), “Governance, Management and the Role of a Board of Directors”, NGOConnect eNews Issue number 12, May 2009, p1-2 http://www.ngoconnect.net/documents/592341/749044/Governance+-+Governance,+Management+and+the+Role+of+a+Board+of+Directors. Accessed on July 3, 2018

iiiMoeller, R. R., (2004), Sarbanes-Oxley and the New Internal Auditing Rules, (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons), p2

ivThe Business Roundtable, (2002), Principles of Corporate Governance, May 2002, p4-8, cited in Green, S., (2005), Sarbanes-Oxley and the Board of Directors: Techniques and Best Practices for Corporate Governance, (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons), p27

vGreen, S., (2005), op. cit., p28

viAustralian Government, Federal Register of Legislation, Corporations Act 2001, https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018C00031, accessed on July 4, 2018

viiCanada Business Corporations Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-44), last amended on May 1, 2018 http://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-44/page-15.html#h-18, accessed on July 4, 2018

viiiCompanies Act 1993, http://legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1993/0105/188.0/DLM320642.html, accessed on July 4, 2018 ixCompanies Act 2009, Government Gazette, Cape Town, volume 526, No32121 April 9, 2009 http://www.cipc.co.za/files/2413/9452/7679/CompaniesAct71_2008.pdf, accessed on July 4, 2018

3.8

3.8