Brigitte, the CEO of a consumer products company, is discussing some troubling organizational trends with Len, her Chief People Officer. Turnover has increased in sales, a function crucial to the company’s ongoing transformation. In the last promotion cycle, fewer managers advanced candidates for promotion than Brigitte and Len have ever seen. A general sense of apathy and malaise seems to have taken hold. Brigitte’s quarterly Town Hall meetings are eerily quiet, but because they are virtual, it’s hard to tell who is actually listening and who has left their desk.

“What if everything isn’t as sunny as we’d like to think?” Brigitte asks Len.

“People are definitely fatigued – it’s been a tough few years,” Len replies. “Your Town Hall messaging has been great, and I’m confident that other leaders have stayed on message in their group-level meetings, too. But it’s hard to know what’s going on with the rest of our employees.”

“What does the people survey say?” Brigitte asks. Formerly the CFO, Brigitte always relies on numbers. The company’s annual engagement survey is deployed like clockwork.

“That’s the strange part,” Len muses. “Except for that first strong dip early in the pandemic, the engagement numbers have barely moved. We don’t look much different than we did three years ago.”

“Maybe it’s time we dug a little deeper,” Brigitte says.

Business leadership is at an inflection point. The tumult of the last few years —multiple waves of the Covid-19 pandemic, geopolitical uncertainty, increased social unrest, and the recent bleak economic outlook — has taken its toll on people and performance. The entire contract between workers and institutions is being re-written, with workers walking away from roles at historically high rates.1

Leaders are concerned. Russell Reynolds Associates’ 2022 Global Leadership Monitor found that 72% of global business leaders believe that the greatest risk to the health of their organization over the next 12-18 months is the lack of availability of key talent and skills. This anxiety outpaced concerns around uncertain economic growth, geopolitical uncertainty, and technological change.

During moments of acute global crisis, culture has the power to pull people closer together or drive them further apart. Notably, culture’s impact depended on people’s original feelings. Midway through 2020, Qualtrics and Quartz surveyed 2,100 workers2 on how their connection to company culture evolved during remote work. Employees who felt well-connected prior to the pandemic felt that their company’s culture had improved, while those who already felt a lack of connection reported that their cultures had deteriorated after the shift to working from home. As we look towards further uncertainty, it’s important to remember that lesson: through times of crisis, cultures can either amplify positivity or enhance negativity. Understanding your organization’s culture is critical to maintaining your people’s commitment.

Measuring what’s happening in your organization and understanding what motivates and energizes your people has never been more imperative.

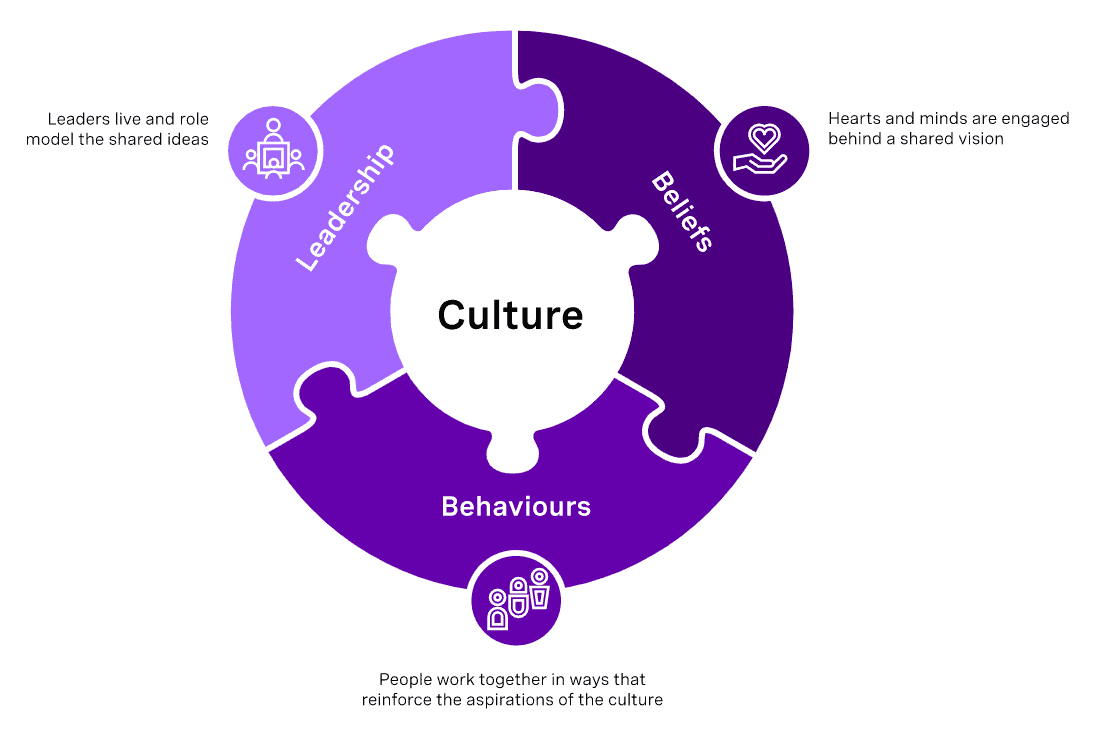

First: What is Culture?

At Russell Reynolds, we define culture as the shared set of assumptions held by people within an organization about who we choose to hire, how we behave, how we lead, what we reward and what we punish. It includes the tone set by leadership at the top of the organization – not just what leaders say, but what they do. It also includes the echo from the bottom: the beliefs and actions that are held and demonstrated broadly across the enterprise. Culture is the difference between an organization chart that makes sense on paper, and the way that work really gets done.

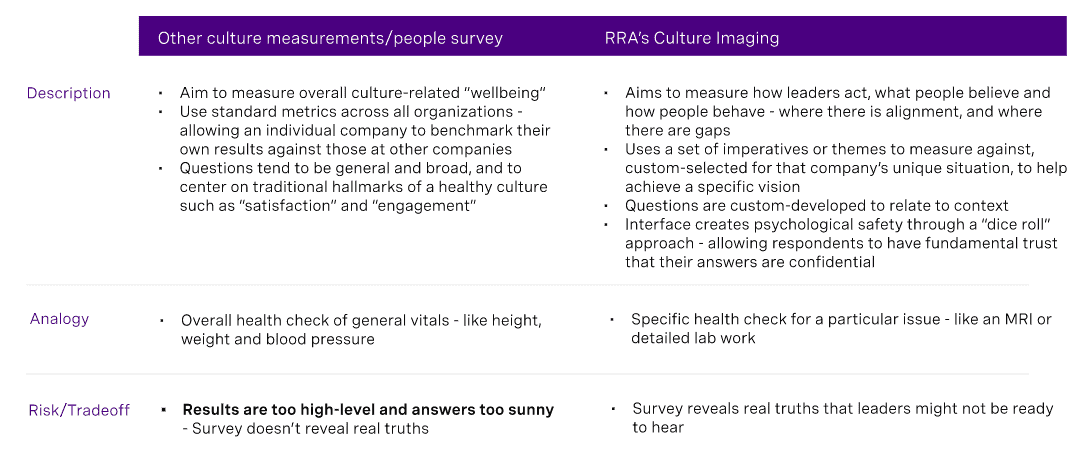

CEOs, people officers and board leaders often want to know if they have a “good culture.” It is critical to ask this question, but impossible to get a simple answer. Cultures are complex systems. Most leaders, like Brigitte and Len, use organization wide-surveys to channel many voices into clear themes, in hopes that these themes will point towards useful action. These surveys are appreciated and important. At a minimum, they are a signal to employees that their opinions matter and that they have a channel through which their perspective can be heard.

Too often, however, the results of these surveys fail to illuminate what’s really going on in an organization. Many leaders find the results of standard measurement tools to be either (a) too broad to be actionable; (b) more positive and encouraging than other signs would suggestion, or (c) both. To help leaders move beyond broad culture measurement approaches and identify lurking organizational issues, this paper:

- Explores the shortcomings of most culture measurement practices

- Suggests targeted, focused methods for identifying cultural issues and outlines Russell Reynolds’ innovations in this space

- Proposes recommendations for the future of culture measurement

Shortcomings of Most Common Culture Measurement Practices

Recall where we left Brigitte and Len: musing on the gap between relatively sunny engagement survey results and a nagging shared sense that the data wasn’t telling the whole story. Unfortunately, this is a common experience. Leaders can understand and control the “tone at the top;” for example, Len and Brigitte were confident that the whole executive team was staying on message. But the “echo from the bottom” is much more elusive. Standard surveys often lack nuance and fail to surface deep-seated issues.

There are a few reasons for this:

1) People are skeptical about the anonymity of their answers. With the drastic increase of those working from home, our devices have begun to feel like an extension of our company. We stare into the abyss of the Zoom camera while Slack and Teams chats fill the periphery. It’s hard to believe that anything we write or say through a company interface—even via a survey that promises confidentiality—is truly anonymous. As a result, it is hard to get accurate answers to any questions, especially those that probe on sensitive issues related to ethics, bias, safety, or commitment.

2) Positivity bias is a powerful, well-documented force. People have a natural inclination to answer questions in the affirmative. Consider the common question, “How are you?” The polite, conventional answer is, “I’m fine.” It takes patience and trust between two people to get beyond that reflexive answer to a deeper truth. Surveys don’t allow for that time to reflect. Most people tend towards a positive initial response, which doesn’t display the actual state of affairs.

3) Most surveys are too broad. When leaders survey their organization, they often strive for comprehensiveness. This instinct stems from good intentions—by asking every person the same question and extending surveys deep into the workforce, these leaders are seeking to capture every voice. The problem with this approach is that it can lead to results that are so broad and general that they are practically indecipherable, leading to a sense that the tool wasn’t subtle or sophisticated enough. Real culture insights do not emerge from direct responses to questions with a clear ‘good’ or ‘bad’ answer—for example, “Do you trust leadership?”—but from looking for subtle variations in responses across business units and over time.

Does this mean that leaders should stop trying to measure what’s happening, and rely instead on pure intuition? Absolutely not. Instead, leaders must find nuanced ways to measure their organization’s culture, which takes more thought, purpose, and innovation than conventional approaches would suggest.

Surfacing the Unspoken: A New Approach to Understanding Culture

Let’s return to our CEO and People Officer, Brigitte and Len. In an ideal world, leaders like them could go deeper, finding accurate (and measurable!) ways to answer questions, such as:

- Are leaders viewed as “walking the talk”?

- Are compliance or safety procedures being practiced with regularity?

- Are there more instances of skepticism and conflict in certain areas of the business?

- Are people’s daily actions and behaviors supporting business strategy and goals?

- Are people’s behaviors aligned with organizational values?

In other words, leaders would be able to pose and answer the tough questions that are difficult to surface through conventional approaches.

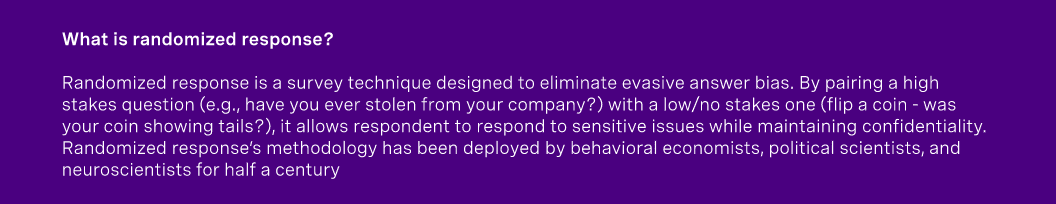

Some forward-thinking leaders have turned to Russell Reynolds’ Culture Imaging Approach, the first corporate diagnostic to leverage randomized response.

Culture Imaging: Getting Beyond “The Yes Reflex”

What if you could persuade people to tell you what they really think, not just what they think you want to hear? This is the idea behind Culture Imaging, a unique approach to measurement that creates real psychological safety for the survey respondent, asking sensitive questions in a manner that creates confidence in its confidentiality. In our experience, this method leads to powerful group level insights about people’s real beliefs and behaviors. These insights have profound implications for employees, leaders, and companies.

Culture Imaging in Action: Risk at ExxonMobil

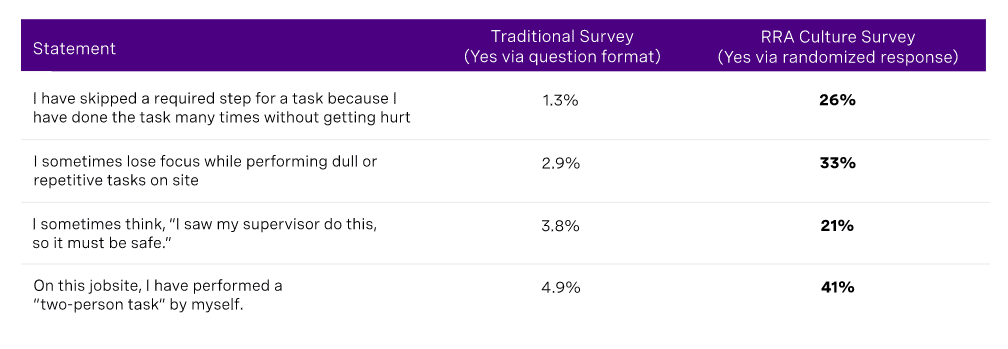

At ExxonMobil, leaders at a job site struggled to understand why safety violations had escalated. They suspected that workers were letting protocols slide, and they worried about how this ongoing behavior might impact both site operations and their workforce’s well-being. They needed to know what was truly happening on the ground, but their own policies made this difficult to surface – workers could be penalized (or even fired) for failing to follow safety rules. According to their ongoing site survey, 98.7% of workers claimed to follow safety procedures to the letter. But this data clearly wasn’t representative of what was actually happening.

Was the problem with the questions themselves, or how they were asked? ExxonMobil allowed researchers to run an experiment to find out.

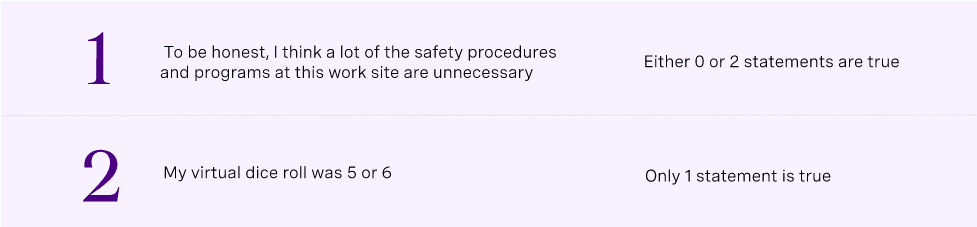

Over 1000 workers—the same ones who had originally been surveyed—were asked to answer the same questions again. Before the questions were asked, they were given assurances that their answers could not be directly attributed to them. Before each question, the interviewee rolled a dice. Next, they were presented with two statements: one “sensitive” one about their safety practices, and a “no stakes” one about their dice roll.

Step 1: Respondent rolls their dice and remembers their number.

This number becomes information that only the respondent possesses, and it ensures their response is 100% anonymous.

Step 2: Respondent is presented with two statements—one sensitive one about their role or organization, and one about the number from their dice role. They are then asked how many of those statements are true.

Because the respondent is answering a statement about the organization in combination with the statement about the dice, their feelings about the first question cannot be known. The second question creates “noise,” and thereby creates anonymity.

When a large number of responses are combined, however, it’s possible to discern how many people agreed or disagreed with the statement at a group level, due to the probability distribution of a dice role (i.e., each number has a 1 in 6 chance of occurring).

Put in another way – it is possible to surface the “true feelings” of a group, without “exposing” the individual. Anonymity is hard coded into the responses.

In using this method, no response could be attributed to an individual, but overall responses to each question could be easily examined through group-level analysis that presumed a random distribution in the dice rolls.

For ExxonMobil, the results were staggering: in this approach, a quarter of workers admitted to skipping safety protocols. Rates of other concerning violations were much higher than previously reported as well

The Future of Culture Measurement

The revelations around the ExxonMobil safety violations demonstrate that providing psychological safety is critical in achieving real answers, and how simple creating that safety can be. RRA’s Culture Imaging approach has been deployed by bold leaders who want to understand the gap between what people are willing to say and how things truly work.

Looking Ahead: Leading with Clear Eyes

Imagine that you were on the leadership team at the ExxonMobil job site, seeing the results of the randomized response questions. It must have been difficult to face the truth of these safety procedure breakdowns, but there was likely some relief as well. Understanding what’s happening is the first step to taking focused action.

If you’ve read this far, you’re probably intrigued by this approach. It’s likely, though, that you identify more with Brigitte and Len than you do with the ExxonMobil site leaders. In other words, you probably sense that there are beliefs and behaviors in your workforce that you need to understand better to take focused action – but you don’t know how to uncover what’s really happening. If you want to be clear-eyed and courageous about the real situation in your culture, consider the following recommendations:

Be clear about what’s mission critical:

The culture you have today is a complex operating system – you can’t expose every hidden truth at once. Explore whether your culture supports your strategic direction and, in doing so, apply the same discipline, resourcing, and focus as you did when setting said direction. Dedicate resources and effort to understanding your situation through focus groups, interviews, and less conventional data sources that might contain tough messages (e.g., Exit interviews are often a powerful and untapped source, as are external company reviews on forums such as Glassdoor).

Invest in cutting-edge cultural diagnostics:

To get an accurate picture of an organization’s existing culture, leaders must ensure they have the right assessment tools and methods. These tools should not only use advanced techniques and statistical analyses; they should also reflect the unique language of your organization so that they are seen as relevant to your employees.

Leverage data for focused action:

Organizations often try to do too much with their culture insights. Keep strategic needs in mind and avoid the tendency to do too much action planning. Focus on select organization-wide and surgical interventions in the areas that matter most.

Create a feedback loop for continuous growth:

Culture is constantly evolving, whether leaders want it to or not. The ability to regularly assess and refocus interventions is nearly as important as getting accurate information in the first place.

The turbulence of the past few years seems unlikely to abate. Companies with strong commitment at all levels will be better equipped to weather these storms. It takes courage and discipline to build that commitment, and the leaders who accomplish it will be those that understand their culture in real, not ideal, terms. Finally, be patient: changing culture takes time.

- Gretchen Anderson leads Russell Reynolds Associates’ Culture capability. She is based in Baltimore.

- Leah Christianson is a member of Russell Reynolds Associates’ Center for Leadership Insight. She is based in San Francisco.

- Eric Wimpfheimer leads Knowledge for Russell Reynolds Associates’ Leadership & Succession capability. He is based in New York.

- Andrew Wood is a member of Russell Reynolds Associates’ Strategy & Development team. He is based in Houston.

The article was first published here.

Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash.

5.0

5.0