Thanks to this week’s contributor, Morio Nishikawa, for providing this case study about the Seibu Group, a Japanese family-owned business that faced a variety of legal challenges beginning in 1993 as the country’s laws changed, and the company’s practices and protocols were not updated. The articles ends with an informative “lessons learned” section.

In 1993, Yoshiaki Tsutsumi, the former owner of Seibu Railway Group, was named the wealthiest man in the world by Forbes, an American business magazine, placing him ahead of Bill Gates, who had topped the previous year’s list. Tsutsumi’s total assets were reportedly worth three trillion yen (US$30 billion at 100 JPY/USD).

Just twelve years after heading the Forbes list, however, he was arrested by the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office on suspicion of violating the Securities and Exchange Act (falsifying statements on a securities report and insider trading) involving the stock of Seibu Railway. At his first trial in Tokyo District Court, he was handed a sentence of 30 months in prison—suspended for four years—and a fine of five million yen (US$50,000). This resulted in the dissolution of any equity relationship between Seibu Railway Group and the Tsutsumi family, and the transfer of controlling interest in the Group to a third party outside the family.1

Seibu Railway was originally founded by Yasujiro Tsutsumi, Yoshiaki’s father. The eldest son of a farmer, Yasujiro was a legendary entrepreneur who made a success of himself, creating the Seibu Group to go up against Keita Goto, who had founded the Tokyu Group. He was also a politician who served as the 44th President of the House of Councillors.

Yoshiaki, Yasujiro’s third son, took over the Seibu Group’s railway group. Meanwhile, another of Yasujiro’s sons, and Yoshiaki’s half-brother, Seiji, took over the Seibu Group’s retail group, Seibu Department Stores.

Still, of all the siblings, Yoshiaki most took after his father. Like his father, Yoshiaki was an autocrat, though one with strong business acumen. Starting in the 1960s, he greatly expanded the scale of Kokudo and Seibu Railway Group’s business, with resort developments including the Prince Hotels, ski resorts and skating rinks, and large-scale development of new suburban residential projects.

At the same time, he worked to minimize corporate taxes and keep profits within the company — a tax-avoidance system so refined that one former employee of the National Tax Agency referred to it as “artistic.” 2 This was an area in which his father, Yasujiro, was especially proficient. Yasujiro saved on taxes by putting his family compound in the company’s name, and by having the company pay for everything from home repair costs to electricity bills and property taxes, and even the salaries of his driver, secretary, and houseboy.3

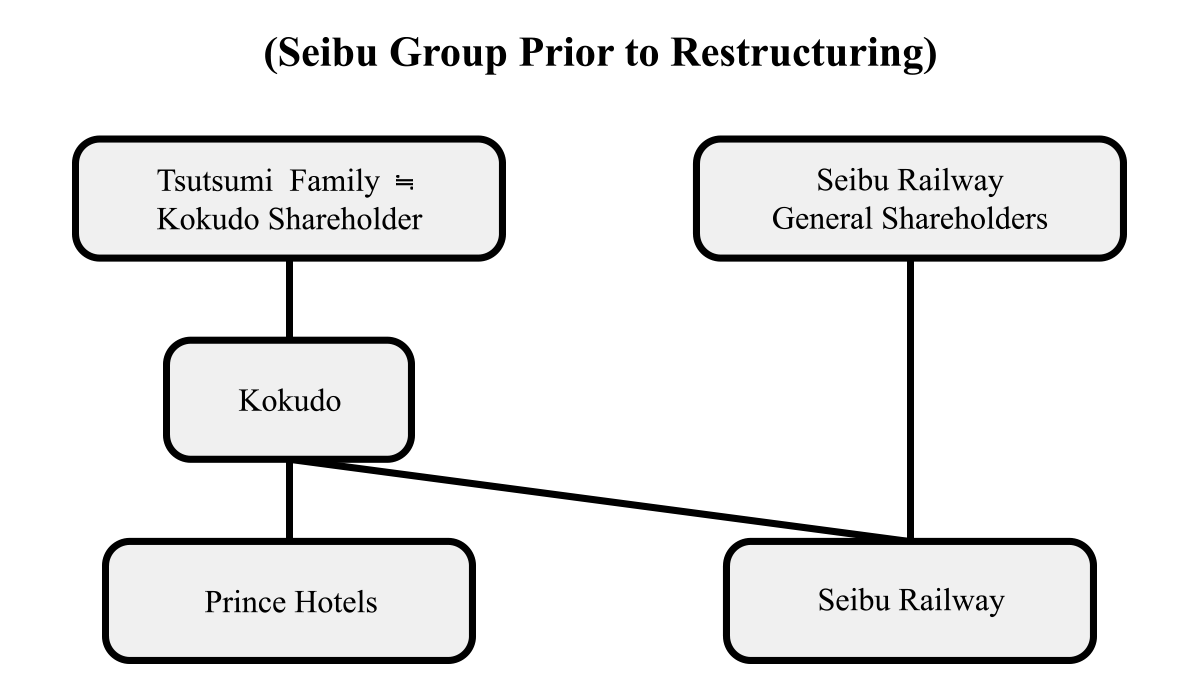

Yasujiro also minimized capital in his group companies, creating a system for ensuring Tsutsumi family control over the business through Kokudo, its holding company. Yasujiro’s tax-saving measures and capitalization strategies were, at the time, a resourceful way of protecting the Seibu Group.

It is likely that, in taking over from his father, Yoshiaki continued to adhere to Yasujiro’s methods. To protect the Tsutsumi family code left by his father, in part stating that, “We must never sell a majority of our shares or allow ourselves to be taken over,” Yoshiaki saw to it that Kokudo retained a vast amount of shares in Seibu Railway, while putting a portion of those holdings in his employees’ names and listing the actual ownership ratio in the company’s securities report.4 Ownership of more than 80% of the company’s shares by its top ten shareholders would put the company in violation of Tokyo Stock Exchange delisting criteria, and this maneuver was intended to prevent its delisting.5

While the report stated Kokudo’s ownership at about 43%, in fact Kokudo not only owned 64% of subsidiary Seibu Railway, but minority shareholders accounted for about 88% in the company, an extremely large percentage. It was also discovered that, prior to this disclosure, Yoshiaki and Kokudo had engaged in a large insider trade amounting to a selling price of 21.6 billion yen (US$216 million).

In today’s world, effective corporate management benefits from a high level of ethics and a spirit of compliance, and rather than a singular pursuit of profit. Seibu Railway’s “fragility” can be summarized as follows:6

- Actions taken solely in the interest of one family;

- Appropriation of the company, lack of discipline and a spirit of compliance as a public institution;

- Long years of autocratic management leading to administrators, employees, and an organization that simply awaited orders;

- Poor awareness of the obligation to pay taxes;

- Inability to move beyond successful models and experiences from the past;

- Excessive clinging to existing corporate culture and methods that left the company behind the times;

- Neglect for reforms and innovation; and

- Lack of clarity regarding the roles of the family, the Board of Directors, and the executive officers.

Subsequently, the company has moved forward with management reforms led by Takashi Goto (the current chairman), who was appointed CEO of Seibu Railway after being sent from Mizuho Corporate Bank to serve on the company’s management reform committee. As shown in Fig. 1 below, the complex web of capital ties between Kokudo, Seibu Railway, the Prince Hotels, and the Tsutsumi family were reorganized with the launch of Seibu Holdings and an infusion of outside capital through a third-party allotment of shares.

In terms of compliance, in particular, the Group’s Corporate Ethics Committee met to formulate the Seibu Group Code of Corporate Ethics and the Seibu Group Action Guidelines, with the goal of establishing a compliance structure for the entire group centered around Seibu Holdings. Compliance Manuals and Compliance Cards, common to the entire Seibu Group, are also distributed to every executive and employee.

Figure 1: Restructuring of the Seibu Group

Source: Seibu Railway Corporate Communications Department

Great Founders: Lessons From This Case

Many company founders are multi-talented, capable of handling—alone—everything from manufacturing to sales, to marketing, to finance. Founding a company is the act of starting with nothing and turning that “zero” into a “one,” which is why, at the beginning, it can require that everything be done by a single individual. Founders are those who have successfully overcome those difficulties. However, one potential issue is that many founders have a stronger-than-average emotional attachment to their companies, and as emotion overwhelmingly wins out over reason, they tend to pick successors who are not suited to the role of corporate leader.

Unconsciously, the founder is constantly comparing his successor to himself, and often is thus never satisfied; as a result, he may insist on clinging to power even in old age.

In either case, what can be helpful is the idea that the founder transfers power to a team of several people, centered around his successor, rather than handing over all of the work to a single successor. While it would be ideal if the founder could turn everything over to a successor just as capable as himself, in reality, such people are rare. While the founder’s shares may be passed to a single successor, the founder should also consider turning the work itself over to a team comprised of individuals who can support that successor in areas where he may be lacking.

Unlike their predecessors, many successors have already studied management theory, at college or elsewhere, and some may have earned an MBA from an American university, giving them an intellectual understanding of management theory. But it is those very types who, in succeeding a founder, need to experience failure on the front lines of the business, because without such experience, they tend to focus their abilities on the kind of theoretical business analysis and management they learned about in school. People have a strong tendency to work hardest at what they do best, which is why effective leaders benefit from experience in areas in which they do poorly. Without this experience, they risk turning into one-sided leaders.

References

1Tateishi Yasunori, Sabishiki Karizuma Tsutsumi Yoshiaki [Tsutsumi Yoshiaki, the Lonely Charismatic Leader] (Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha, 2005)

2Matsuzaki Takashi, Seibu Teikoku no Kobo [Rise and Fall of the Seibu Empire] (Tokyo, Japan: Nikkei BPNet, 2006)

3, 4, 5Ibid.

6Nishikawa Morio, Nagaku Hanei Suru Dozoku Kigyo no Joken [Conditions for the Long-term Prosperity of Family-owned Companies], (Tokyo, Japan: Japan Management Consultants Association)

About the Contributor

Morio Nishikawa, CFBA, is the chairman of Yokohama Consulting Co., Ltd, a consultation company for family business and provides consultations to many companies as the independent director and the advisor. He completed the Advanced Program (A.M.P.) at Harvard Business School and is the author of the book “Conditions of A Successful Family Company.” He was for many years the leader for both Consumer (B2C) and Professional (B2B) Divisions at S.C. Johnson, a renowned global family company. Morio can be reached at morio.n@yokohamaconsulting.com.

Morio Nishikawa, CFBA, is the chairman of Yokohama Consulting Co., Ltd, a consultation company for family business and provides consultations to many companies as the independent director and the advisor. He completed the Advanced Program (A.M.P.) at Harvard Business School and is the author of the book “Conditions of A Successful Family Company.” He was for many years the leader for both Consumer (B2C) and Professional (B2B) Divisions at S.C. Johnson, a renowned global family company. Morio can be reached at morio.n@yokohamaconsulting.com.

The article was first published by FFI Practitioner here.

Photo by Antonio Lapa on Unsplash.