Why you can—and should—manage your company’s culture

Culture is often viewed as the magical elixir that makes great companies great and there is ample evidence that cultures steeped in innovation, fellowship and other good things have a pervasive effect. But culture is not an arcane art. It is the outcome of decisions—conscious or otherwise—about an organization and the best companies take an active hand in managing their cultures.

Why Culture Matters

CULTURE tends to be something of an enigma in the study of companies. Everyone agrees over cocktails that culture is important and hopes their company has a “good” culture versus a “bad” culture. For all of its implied significance, however, cultural change tends to rate alongside tarot card reading and astrology in terms of credibility. It lurks in the unfortunate category of “soft” issues that leaders can’t quite discard for the nagging sense that there may actually be something there, something that may hold too much importance to dismiss out of hand.

The Hard Truth

In fact, culture is not a “soft” issue created by cheerleading, posters or picnics. Culture can be explicitly defined, and it generally develops out of tangible (and controllable) actions within a company, not in a murky black box. Moreover, its implications for corporate performance are real and can be substantial. Research from Denison Consulting concludes that companies demonstrating higher levels of performance in key areas of corporate culture, including adaptability, consistency, mission and involvement, deliver better results when it comes to return on assets, sales growth and increased value to shareholders.1 This finding builds on J. Kotter’s and James Heskett’s landmark 1992 study,2 which found that, over a 10-year period, companies that intentionally managed their cultures outperformed similar companies that did not. Their findings included revenue growth of 682 percent versus 166 percent; stock price increases of 901 percent versus 74 percent; net income growth of 756 percent versus 1 percent; and job growth of 282 percent versus 36 percent.3 Additionally, companies listed on Fortune’s 100 Best Companies to Work For further demonstrate that those with well-managed cultures significantly outperform the S&P 500.

Culture similarly can take on increased importance in large corporate mergers and acquisitions, where an estimated 30 percent of integrations get stuck or fail outright as a result of cultural issues. Disparities in corporate culture, as well as the tendency for one culture to become dominant, create a “win-or-lose” mindset that injects a good dose of mistrust into an already complicated process.4

Culture as a Driver of Business Results

Beyond the hard numbers, culture can play a prominent role in several issues that top business leaders’ agendas. Ethics, which has become something of an obsession in the wake of the Enron fiasco and the resultant Sarbanes-Oxley Act, hinges on effective controls, proper systems, and, most important, a culture that values ethical behavior and discourages dishonesty. If ethics can be defined as what one chooses to do when no one else is watching, then culture can be a significant predictor of ethical or unethical behavior. Building systems and controls as a sort of scaffolding around a dysfunctional company can be an (expensive) exercise in futility.

Business publications also are replete with stories about the war for talent and innovation as a driver for growth. Jeff Rosenthal and Mary Ann Masarech put a finer point on it: “Organizations depend on innovation for growth and high performance, which in turn depend on employee initiative, risk taking and trust-all qualities that are either squelched or nurtured by an organization’s climate.”5Moreover, they add, people are increasingly looking for more from their employment than a paycheck. Some “sense of purpose” and camaraderie, even joy, fit into many workers’ notion of a great job, and projected demographic trends suggest that retaining top talent will become increasingly important as the talent pool, and working-age population as a percentage of the total population, diminishes. If a company wants to attract and retain the best and the brightest, culture once again emerges as something that truly matters.

And as for the genius of innovation, clearly the one percent spark of inspiration is nurtured by a positive culture. But the 99 percent perspiration ingredient comes from employees who love what they do, as well as where they do it, and who invest in that Holy Grail of productivity called “discretionary effort.” We believe that the spark and commitment of employees in these “good” cultures are a big part of what creates extraordinary results.

Not a Roll of the Dice

The crux of it is this: A high-performance culture can be a competitive weapon that leaders can actively manage. Culture should not be something that simply happens and through a fortuitous roll of the dice turns out in a way that works for us. It is the product of behaviors, symbols and processes which should be controllable and contribute to or detract from a company’s performance.

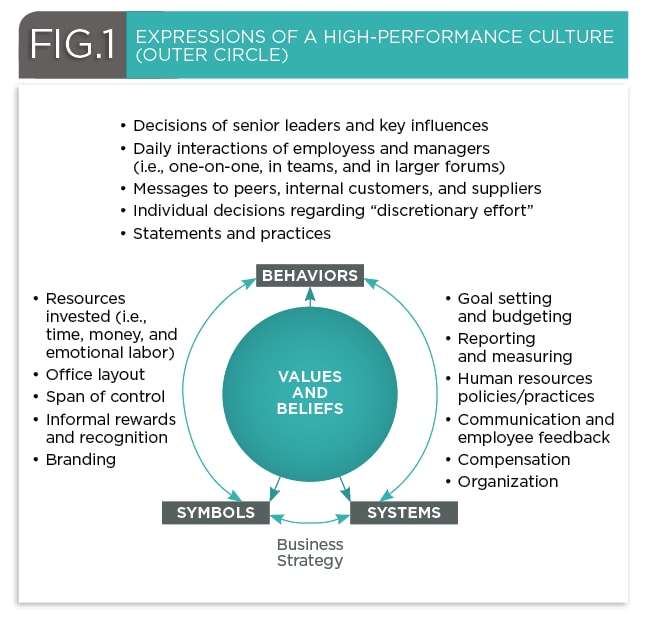

The interplay among all of these elements—inherent values and beliefs, visible systems, behaviors, and symbols—set against the backdrop of business strategy, represents a company’s culture.

Anatomy of a High-Performance Culture

Everyone wants a high-performance culture that gets the job done while attracting the best and the brightest. But just what is it? Not all definitions agree, but behaviors, symbols and processes are visible manifestations of a company’s culture.

A high-performance culture is “an integrated set of management processes focused on extraordinary performance,” according to Dr. John Sullivan, professor at San Francisco State University and noted strategic human resources author. What it’s not, Sullivan adds, is a corporate culture in the traditional sense, encompassing such things as values and beliefs.6

When Kotter and Heskett examined the causality of corporate culture and performance in the late ‘80s, they divided culture into two parts: (1) the pattern of shared values and beliefs that helps individuals understand organizational functioning (invisible) and (2) those conventions that provide them with norms of behavior (visible).7 In the authors’ view, because behaviors manifest themselves in such decisions as how to invest the company’s resources, it makes sense to add symbols and systems (processes and infrastructure) to the equation as visible expressions of culture. In short, the model used here (Figure 1) combines Sullivan’s description of a high-performance culture with Kotter’s model while focusing on the expression of culture as a direct result of shared values and beliefs. The interplay among all of these elements-inherent values and beliefs, visible systems, behaviors, and symbols-set against the backdrop of business strategy represents a company’s culture.

Do as I say…

In a high-performance culture, values and their visible expression in behaviors, symbols and systems are inextricably connected. It is not enough to focus on systems in isolation or print more posters about values with no credible incentive for behavioral change. Symbols are equally integral to establishing and maintaining culture. How many employees get mixed messages when the company’s new cost-savings initiative is promoted during an expensive corporate event? Or worse, during an event they are not invited to attend!

But Which Type of Culture?

The actual culture of a company is most often revealed when observing how individuals approach and complete tasks and activities. This depends on decisions made in line with business strategy and can sometimes differ from officially declared values. As discussed above, how employees choose to expend discretionary effort on behalf of the company is a direct reflection of the culture, either high-performing or not.

Consider another common scenario: A company implements the latest human resources information system (HRIS) or enterprise resource planning (ERP) system only to find employees resisting the new way of doing business. The clash becomes much easier to understand when viewed in light of the inherent behaviors and symbols of the company, which, unless they were actively changed, are (surprise!) still supporting and rewarding the old organizational structure. This is where systems and process change need to go hand-in-hand with intended behavioral change.

Efforts to change culture solely through recruiting or a flashy communications campaign often miss the point, as do the frequent horror stories about companies implementing performance-tracking software to “solve the culture problem.” There’s usually more to the mix and companies must use the ingredients they have at their fingertips-behaviors, symbols, and systems.

Unlocking the Black Box

We believe that a high-performance culture that meshes with business strategy will result from consistent and appropriate decisions on those aspects of the company that are anything but “soft”: behaviors, symbols, and systems.

1. Link before you leap

Before diving into the churning waters of cultural change, it’s important to take a step back and question the purpose. What sort of culture is most in line with the company’s strategy and, as important, how does this compare to the way things are done now? How do we understand where we are today?

As an example, at a Medicaid agency in the Northeast, a survey found employees giving low marks to virtually every cultural attribute, marking the distance between actual and ideal as quite large. Culture assessment tools can help to map present and desired-state culture as a way to identify a list of desired behaviors. A comparison of today’s cultural attributes to those desired is often used to indicate where the biggest bang can come from when changing a company’s behaviors and culture.

But companies don’t get paid for finishing at the top of the annual culture awards: They meet or exceed their business objectives by gaining market share and becoming more profitable. And while culture can be influenced by outside factors (competition, industry structure technological change, for example), it also is an aspect of the company that should be managed with an eye toward improving the company’s ability to meet or exceed its business objectives.8

In one case, Deloitte Consulting LLP provided a national bank with survey research results on banking industry “success” factors. The information was used to help the bank assess its current culture and how it worked with its business strategy. Tangible metrics were identified, among them attrition and acquisition numbers, data that can help provide important insights into deficient processes and/or strategies. This information can help suggest which cultural attributes have a direct correlation to how effectively a company is reaching its strategic goals.

In the banking survey above, those customers whose attitudes toward their bank were ambivalent, and those who were vulnerable to switching, listed such items as “high switching costs” and “location and access” as leading reasons for remaining with their bank. At first blush, these seem good enough reasons and may even reflect an advantage in real estate and breadth of service. At the same time, however, the third group, the loyal customers, rated “customer service” as the overriding attitudinal factor. This has clear ties to behavior that reflects underlying culture. Moreover, such advantages as fees and locations are fairly easy for a competitor to emulate. But culture change doesn’t occur overnight, and a bank whose culture is conducive to a better customer experience has a competitive advantage not easily copied.9

As even this brief example suggests, culture is an issue that extends well beyond the HR department. There is a danger in confusing culture with morale or any other narrow measure. We believe that culture has an enormous influence on how a company does business and in defining how a company should conduct its business. And for culture to be competitive, it must find its source in this strategy.

2. Gather strength and reinforcement from symbols and behavior

A possibly apocryphal story relates the tale of a woman who shows up at an upscale department store and demands a refund for a set of defective tires. Of course, this store doesn’t sell tires and never has. Legend has it, though, that the salesperson authorized the refund.

Whether this story is true hardly matters because it is widely told, having taken on a life of its own, and the symbolism is clear: While almost every retailer has placards saying that the customer is always right, this particular department store embraced the idea in an extreme way. Reverence for all customers at this retailer requires sales associates offering handshakes following any sale, coming around the counter to hand customers their purchases, and providing their personal business cards to customers. Handshakes aren’t expensive, but their meaning is clear.

Mergers: Matches Made in Heaven—or Not

Mergers present a unique set of challenges on many levels, but it is cultural compatibility that is often overlooked or underestimated. Kell and Carrot “found a greater incidence of successful mergers between companies in which employees displayed similar leadership styles or where the cultures tolerated different ones.” They went on to note that while a company’s culture can be changed at least slightly, vast change may depend on the ongoing “hiring of people who represent the direction in which you are headed.”

Source: Thomas Kell and Gregory T. Carrot, “Culture Matters Most,” Harvard Business Review, Volume 83, Issue 5; p. 22, May 2005.

• Say it and show it

Great cultures aren’t e-mailed into existence and poster campaigns portraying the joys of collegiality aren’t much better. Symbols and behaviors, however, do speak loudly. In effecting cultural change, top-down and tangible are the bywords. Executives who embody the performance culture have license, in the minds of employees, to expect the same throughout their organization. Leaders should speak and do openly what supports the desired culture and be heard and seen in the process.

Is the company president sitting behind his or her desk and reading status reports on customer service issues, or visiting the call center and handling the occasional call? Did the company acquire an inline skate division because the accountants thought it made sense, or is the head of marketing a weekend inline hockey player? Does the company sponsor a league? Are employee ideas slipped into a suggestion box and forgotten or does the company hold live meetings to argue about the ideas? Are offices reserved for executives and cubicles for junior employees? Is someone part of a team of three, or do he and several hundred coworkers report to one manager?

To some degree, every aspect of the work experience expresses the culture of the company. Context is essential and annual photo ops with the rank and file are nothing compared to executives’ behavior modeling in real business situations. Big-production rollouts or cafeteria style culture-building that throws in three months of coaching to solve the “accountability problem” are both common and superficial. Reality is what people touch, see and hear, and there is no campaign that can override a visible executive role model or a thoughtfully-designed environment that shows junior employees are valued.

When misused, symbols can offer a tempting shortcut, but any change in culture requires time, effort and a learning process. The notion that a “culture change” team, even with executive backing, can impose a mindset on employees is flawed. Real change, cultural or otherwise, involves real debate and leader advocates. It has been said that disagreement is the key to getting agreement; without disagreement, there is no testing. Employees may fall into line, but there will be only compliance to directions given, with no commitment to the programs or their strategic intent.

So symbols can be negative, with unintended consequences, or positive and inspiring. Both are powerful and capture attention. Positive symbols can be sincere and real or humorous hyperbole. Both kinds have their place and both work to build and sustain culture change.

3. Build support through organizational systems

The way a company conducts business can play a fundamental role in defining its culture. Among the worst mistakes any company can make is to focus on the benefits of a business process and the information system that implements it in isolation. There is an inextricable link between the design of the steps involved in the collective tasks of a company and the way people work together, or apart.

We have found that in well-run companies hiring takes place with an eye toward attracting people who will support and thrive in the company culture. These companies have performance management and reward systems designed around specific behaviors that complement the business strategy, not around a generic list of positive accomplishments.

Systems can aid leaders in governing a company and include these important categories:

• Performance management systems

What is rewarded gets done. Period. Performance ratings and compensation remain the fundamental rewards mechanism. We have found that compensation is unfortunately also among the most sensitive areas to change in many companies. As a result, the tight links between performance and adoption of new desired behaviors are often deferred. Badly calibrated or disconnected performance and rewards systems can override virtually any other cultural imperative.

• Talent management systems

The talent management life cycle encompasses recruiting, developing, deploying and connecting employees within a company. Each aspect helps to create and foster the attributes of the company’s culture. For example, a company can actively recruit new hires based on culturally consistent, desired behaviors and reinforce these when people join the company. Among existing staff, who are the high-potential employees based on the new attributes? Which experienced employees were on board with the new culture even before it became the new culture? It is possible, and helpful, to identify both near- and long-term role backups based on new attributes; often this may involve looking to other divisions or functions. If the criteria are based on attributes and behaviors, then functional experience becomes a part of the equation, as opposed to the entire equation, for succession planning.

Top-down behaviors (not e-mails, but visible actions!) can have a significant impact, as noted. Culture change should be linked to leadership assessment and development programs because leaders have the biggest impact. After all, that’s why companies spend so much time seeking the right candidate for the CEO spot. If it’s important that the customer support and order-handling teams support the new culture, it is crucial for the management team to serve as a constant role model.

• Work systems

Assuming that systems support the focus of the new culture, they can be helpful to explain the rationale behind the processes. They can corroborate that the reason things are done in a certain way is not arbitrary or mandated by IT but because the company values the result. If smart, independent decision-making is a key new behavior, for example, coaching in this skill can both help employees develop better skills in this area and serve as a visible symbol of this new emphasis for the company.

The converse is also true: Work systems that are implemented without regard to culture can undermine much of what leadership hopes to achieve. An ERP system implemented at an oil company, as an example, resulted in cost savings in data processing. However, it imposed customer-facing processes that reduced the company’s ability to tailor the product to customer needs and constrained what had been a productive culture.

Systems are so fundamental to culture that it is hardly a stretch to suggest that cultural change in the absence of in-depth process knowledge and experience is an exercise in futility. The converse also seems to hold: processes contorted to fit the latest information systems are usually a disaster-in-waiting as they affect culture.

We believe this interplay among symbols, infrastructure and behavior is the key to cultural change. Deloitte Consulting experienced this firsthand at the Medicaid agency described above, where we helped to develop a Cultural Action Plan that focused on changing symbols and systems to help shape and sustain an improved culture. The plan helped the agency in its efforts to:

- improve its performance management system to increase accountability, customer service, and staff involvement

- institute a simpler process for hiring new employees

- use a behavioral interview guide that guides interviewers to ask candidates how they have demonstrated the desired values and behaviors in previous roles

- create performance expectations at all levels, signed by employees at each level and posted in a public place

- restructure reporting lines to produce a flatter, more accountable organization

- train staff and supervisors in the skills needed to do their jobs and to provide better guidance and direction to their staff

- hire a communications director to improve both internal and external communications.

Beyond recruiting with an eye to the new culture, the agency made tangible changes to core characteristics, right down to its structure. While it may seem like a footnote, the public posting of performance expectations across levels represented a dramatic change in openness and accountability in an organization where these had been notable weaknesses.

4. Measure outcomes repeatedly

Even with supportive symbols in place and systems properly aligned, a company’s culture can be buffeted by competitive and technology-related pressures, making it periodically necessary to determine whether the company is on track. Measurement is essential, and it also can be difficult, as anyone who has administered any kind of “corporate happiness survey” can attest.

In a high-performance culture, the most accurate metrics should be associated with outcomes. For example, suppose a company was striving for a culture that supported and shared innovation rather than one that ceded product and service ideas to the hoarding that can happen in a competitive environment. One (bad) way to measure this would be to survey everyone to find out whether they felt good about sharing ideas. A better approach, however, would be to assess how the company had done in terms of producing ideas and how those ideas had generated income for the company.

Sometimes anecdotal evidence can serve as confirmation. At the Medicaid agency, symbols and systems were changed to support the new culture, and behavioral change occurred over time. But even early indications pointed to positive behavioral change. During a supervisor training session, a supervisor told of how two staff members came to him with a concern that he had not done something according to policy, demonstrating their willingness to hold him accountable. This represented a clear behavioral change from the earlier, dysfunctional culture at the agency.

“Our culture has traditionally not been very performance-focused,” the agency director said. “The cultural transformation that we are undergoing now will not only improve employee engagement, but I also anticipate that it is going to drive employees to achieve results. For example, our claims unit has been battling a backlog that seemed insurmountable. We were able to reduce the backlog by 65 percent over the last two and a half months by focusing on performance metrics. This would never have been possible in the past. The cultural transformation has brought a shared sense of mission.”

Measurement also is worth attention because human behavior is notoriously difficult to predict. Even in a company that astutely manages cultural change, it’s rare to have addressed everything the first time out. Measurement allows for course correction and reinforcement as needed.

Not a Black Box

Commitment matters. Companies whose cultures generate commitment and support their strategies win in the marketplace. They use their talent more fully than their competitors, where cynicism, confusion, frustration, and echoes of “what’s in it for me?” sap energy and motivation.

Companies and leaders who inspire their employees find that their employees in turn inspire their customers. And just as companies that delight their employees can expect significant “discretionary effort” from their workforce, so, too, can these same companies expect to see significant “discretionary revenue” from customers willing to pay more for excellence in their interactions with a business. Positive culture leads to positive cash flow.

The goal in revisiting and augmenting Kotter and Heskett’s model with the concepts of symbols, behaviors, and systems has been to focus attention on the visible manifestations of a high-performance culture. While recruiting the right people remains important, and a charismatic leader can be an asset, the best results have most often come in companies that consider their symbols, behaviors and systems in concert with their desired culture. Moreover, that desired culture is one that fits the company’s competitive strategy in its market. These companies do not see their culture as static, but rather as a part of the business model that helps them achieve their strategic objectives and financial goals.

In the coming years, companies will have no choice but to rethink their company culture and whether it can help them achieve their business vision in the face of global competition and talent scarcity. Opportunities to seize culture as a competitive weapon will become apparent to some and remain a mystery to others. In the meantime, it is important to recognize that culture happens, but not in a black box.

So symbols can be negative, with unintended consequences, or positive and inspiring. Both are powerful and capture attention. Positive symbols can be sincere and real or humorous hyperbole. Both kinds have their place and both work to build and sustain culture change.

The article was first published here.

Photo by Jason Goodman on Unsplash.

5.0

5.0