Building a healthy, high-performing top team doesn’t happen by accident—it’s a deliberate, ongoing process. CEOs who commit to this priority can build a sustainable competitive advantage over time.

Imagine an executive meeting room. The topic at hand is the company’s international growth strategy. Several paths lie ahead—acquisitions, joint ventures, or organic entry into new markets. Each offers advantages but also significant risks. When the CEO finishes speaking, silence fills the room. After a lengthy pause, the CEO offers his perspective. Heads nod. A few polite murmurs of agreement.

This article is a collaborative effort by Fabrice Desmarescaux, Gautam Kumra, Joydeep Sengupta, and Mukund Sridhar, with Jennifer Chiang, representing views from McKinsey’s Center for CEO Excellence; Aberkyn, a McKinsey company; and McKinsey’s People & Organisational Performance Practice.

At first glance, it seems that the CEO has hit upon the best path forward—but maybe not. A polite discussion about an important, difficult decision often signals a deeper issue: an underperforming top executive team. Perhaps the artificial harmony is a sign that the team does not feel safe enough to share their perspectives or debate the required trade-offs. Or perhaps they are unsure of their role in the decision. Whatever the reason, the CEO has a serious problem.

Building and managing a high-performing team is a high-stakes endeavor for every CEO and organisation. In today’s increasingly complex business landscape, teams are the catalyst that propel organisation-wide transformation. McKinsey research indicates that transformations anchored in team-centric approaches can deliver lasting impact and improve organisational efficiency by up to 30 percent.[1] At the very top of an organisation, the stakes are even higher: Companies whose top executive team is aligned and working effectively together are almost twice as likely to achieve an above-median financial performance.[2]

The McKinsey Center for CEO Excellence (MCCE) is McKinsey’s dedicated offering focused on CEO development. MCCE is anchored on the book CEO Excellence, written by McKinsey senior partners Carolyn Dewar, Scott Keller, and Vikram Malhotra. The research underpinning the book is based on more than 20 years’ worth of data on 7,800 CEOs from 3,500 public companies across 70 countries and 24 industries.[1] The flagship MCCE journey involves a unique nine-month CEO Excellence program, tailored to help CEOs elevate their performance and reach their full potential.

MCCE partners with Aberkyn, a McKinsey company specialising in leadership and culture transformation, to deliver workshops, coaching, and learning journeys for CEOs focusing on top team management and broader leadership development areas. Aberkyn is home to a community of over 180 experts—world-class program designers and facilitators who combine deep transformational skills and business acumen—and has served over 300 clients globally.[2]

McKinsey’s People & Organisational Performance Practice brings together McKinsey’s leading experts in leadership development, culture transformation, organisational performance and talent to help organisations unleash sustainable performance through their people.

Through the McKinsey Center for CEO Excellence, we have engaged with nearly 200 global CEOs and former CEOs (see accordian “About the McKinsey Center for CEO Excellence, Aberkyn, and McKinsey’s People & Organisational Performance Practice”). Most of these leaders view team building as a burning platform: Over 70 percent of the CEOs in our CEO Excellence program choose building, retaining, and growing effective top teams as their number-one development priority as leaders.

But what factors really matter in building a stellar top team? And, crucially, what concrete actions can CEOs take to get there? This article draws on new data—covering close to 30 global companies, with a focus on Asia[3]—to answer these too-often-neglected questions, as well as providing multiple real-world examples of successful top-team transformations and their impact on team morale, alignment, and performance.

Buildings A Star Top Team: An Imperative for CEOs

Leo Tolstoy may not have had the corporate world in mind when he wrote “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,”[4] but this statement could easily apply to the team-building context. Dysfunction among top teams is surprisingly common, even in large companies; according to Harvard Business Review, nearly 75 percent of cross-functional teams are dysfunctional.[5]

In a previous article, McKinsey used data from more than 100 teams at various levels within global organisations to debunk common myths about team performance.[6] This article builds on that research but focuses only on the performance of a CEO’s top team. When CEOs step into the role, they have to reexamine, and in many cases jettison, a number of long-held assumptions about top teams.

One common misperception is about the role that top teams should play. In traditional hierarchical organisational models, found quite often in the Asian corporate context, leaders frequently employ a “hub and spoke” leadership model in which CEOs make all the critical decisions and then task team members individually to execute. While this leadership model may work at lower levels within an organisation, it breaks down as individuals rise through the ranks and encounter more complex problems. In today’s volatile and uncertain world, a top team needs to operate as a strong, cohesive unit to navigate all the disruptions.

There can also be a misperception about what a high-performing top team should look and feel like. Our opening scene, for example, illustrates that a top team that does not evince any real disagreement may actually have deep-rooted issues. The truth is that the best top teams actively embrace healthy conflict, surface uncomfortable truths, and consistently call out the elephants in the room.

A further misperception can be around how top teams come about. The art of how to build a corporate team is rarely, if ever, taught in any management or leadership school, where it is often regarded as a one-off team building exercise during an annual strategy meeting. What comes to mind when you think of a stellar team? Perhaps it’s a favorite sports team, a symphony orchestra, or an elite military unit. What all those teams have in common is that they relentlessly practice working as a cohesive unit. For example, in the English Premier League—one of the best soccer leagues in the world[7]—teams play just 38 games per year, with the majority of their time spent in training. A similar principle applies to top corporate teams: To be “match fit” for the big moments, teams need to have spent a considerable period learning how best to work together.

An Evidence-Based Approach to Understanding Top-Team Health

We investigated 14 annual literature reviews and more than 140 published documents on the topic of effective teaming, resulting in a research-backed framework that outlines the drivers of team effectiveness. This framework was used to build the Team Effectiveness Index (TEI), which is based on a diagnostic—taken by each member of any team—that was tested and refined through two rounds of pilot studies.

The TEI diagnostic

The diagnostic tool underpinning the TEI asks individuals to score themselves and their fellow team members across two key dimensions:

- Team health. Scores relate to perceptions of behavior-based inputs across the 17 drivers of top-team health.

- Team performance. Scores relate to perceptions of a team’s current outputs, based on efficiency, innovation, and results.

Across both health and performance, aggregate scores per driver are given as net effectiveness scores (NES), which are calculated as the percentage of individuals who gave a high score minus the percentage that gave a low score. A higher NES indicates higher effectiveness. The overall team score for health and performance is an average of the net effectiveness scores of the relevant sub-elements.

The data set

The insights offered in this article are based on survey results from 354 top-team members across 28 major companies globally. Of these companies, a majority are from Asia–Pacific, followed by the Middle East, Europe, and other regions.

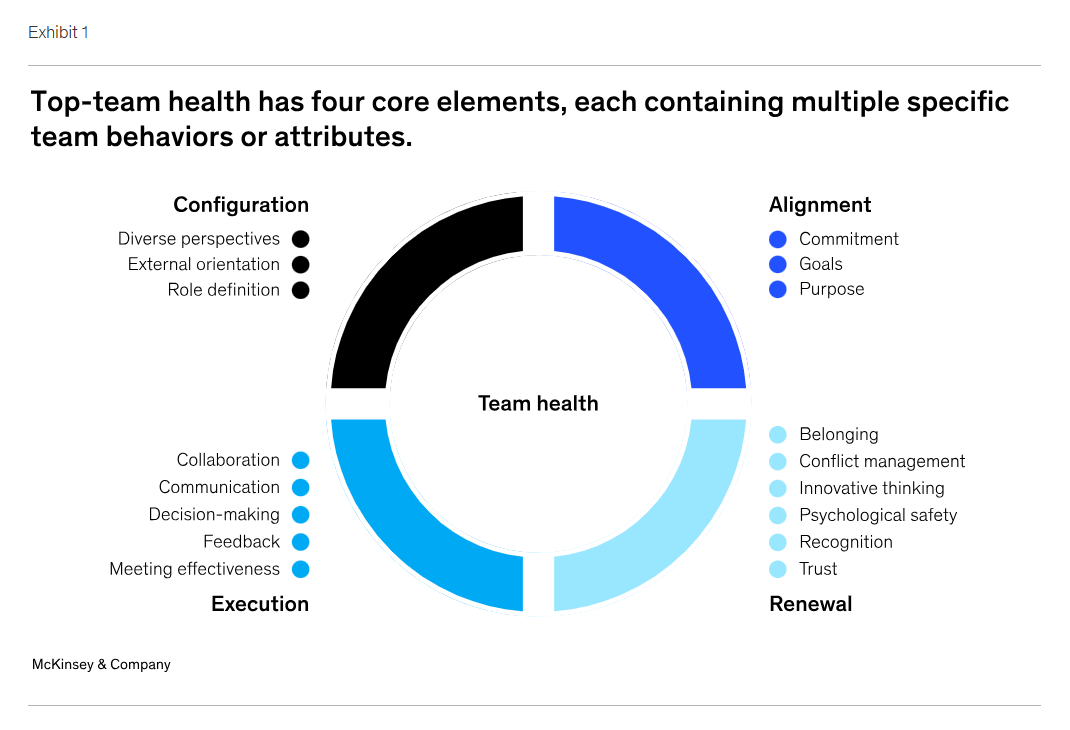

To build a high-performing top team, CEOs must take a disciplined, analytical approach to understand both what is currently working and what is not. Based on extensive global research (see accordian “About the research”), we have identified specific team attributes and behaviors, or health drivers, that matter for team performance (see sidebar “Details on the drivers of team health”).

These team health drivers are grouped into four core areas (Exhibit 1): configuration (the team has clear roles and a mix of perspectives), alignment (team members are clear on the team’s direction and are committed to it), execution (how well the team carries out its work), and renewal (team members’ interactions with each other emanate positive energy and set them up for long-term sustainability). By analysing top-team health drivers across these four areas, CEOs can get a well-rounded view of team effectiveness.

Common Challenges Across Top Teams

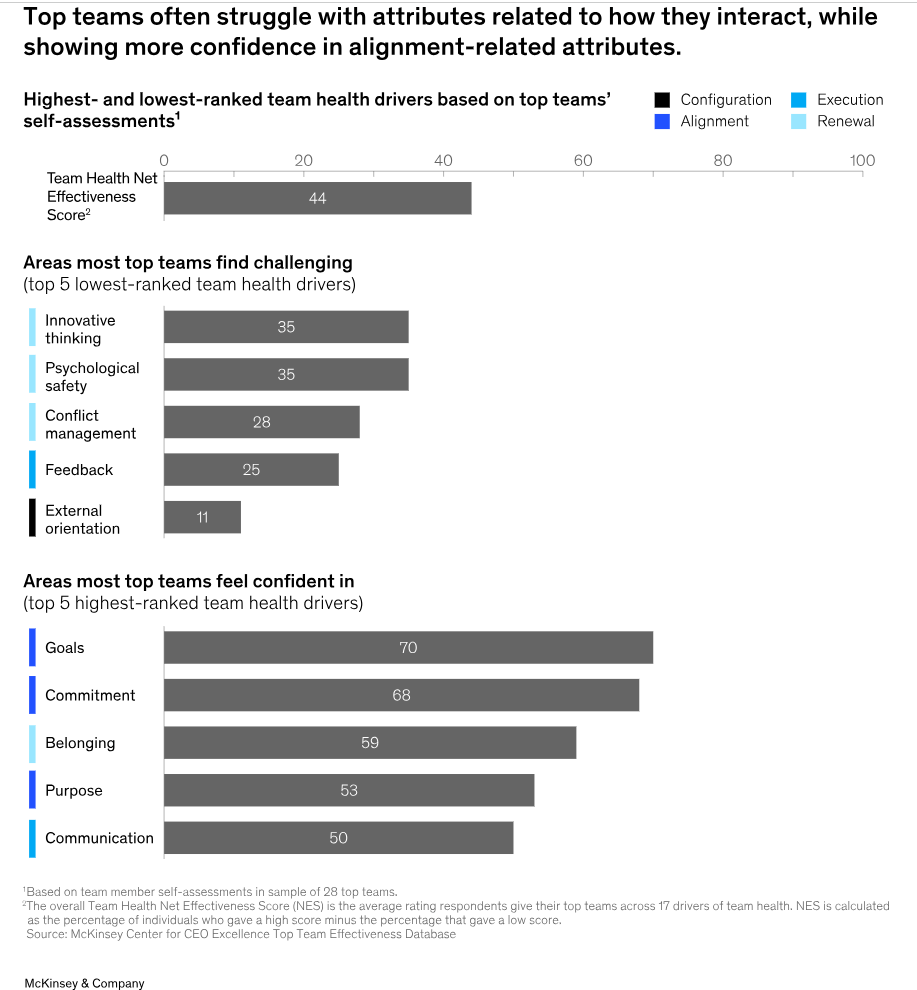

Our data suggests that top teams consistently struggle with attributes related to how they interact, such as psychological safety, conflict management, fostering innovative thinking, and an open-feedback culture (Exhibit 2). These issues are rarely discussed openly and are rooted in deeper team dynamics. While our sample size is not large enough to enable a look at regional differences, lower scores on conflict management and feedback may reflect the conflict avoidance tendencies often observed in Asia-based companies.[8] On the other hand, respondents reported higher scores, on average, on alignment-related attributes, including commitment, shared purpose, and the existence of goals aligned to the organisation’s vision.

Translating Top-Team Health Into Strong Company Performance: What Matters Most?

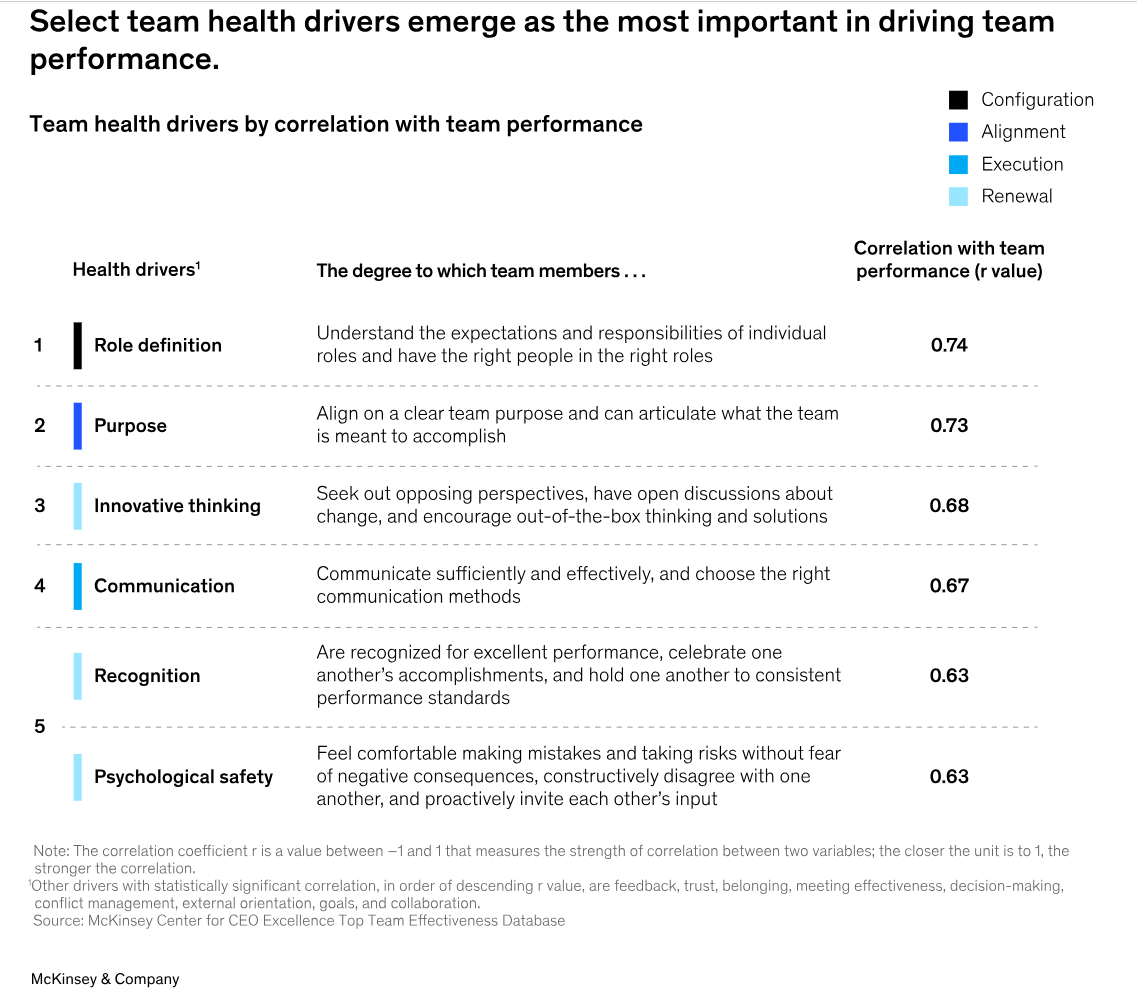

To understand what truly matters for top-team performance, we looked at how these health drivers correlate with a holistic performance indicator.[9] Our analysis suggests that the attributes and behaviors most predictive of high performance[10] are role definition, purpose, innovative thinking, communication, and (tied for fifth place) recognition and psychological safety (Exhibit 3). While two of these drivers—purpose and communication—are among those on which top teams tended to rank themselves the highest, two others—innovative thinking and psychological safety—rank among the weakest, suggesting they may need particular attention.

There are slight nuanced differences between these top drivers and those identified in the previous McKinsey article[11] as a result of both the different types of teams surveyed and differences in the geographical makeup of the samples (see accordian“Key differences between the top-team data set and the full-organisation data set”).

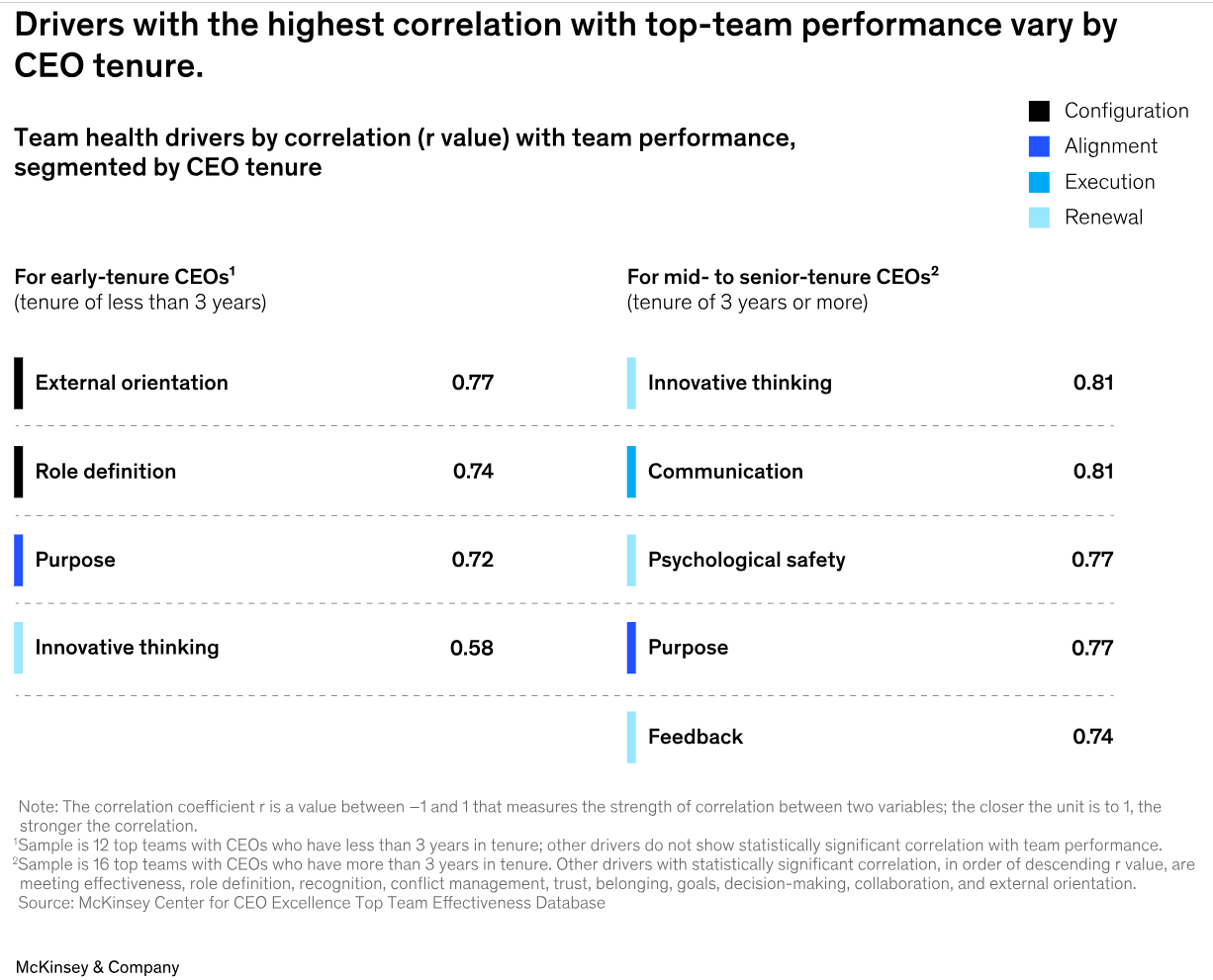

Our analysis also suggests that the relative importance of core top-team attributes may shift over the course of a CEO’s tenure (see accordian “Drivers of top-team performance may evolve with CEO tenure”). For CEOs who are early in their tenure, having clear role definition and leveraging both external and internal perspectives are the standout predictors of top-team performance, while innovative thinking, communication, and psychological safety become more important as the CEO settles into the role.

How do the drivers of top teams compare with the drivers of teams at all levels within an organisation, as identified in the previous McKinsey article?[1] Communication and innovative thinking were among the top five—and role definition is also important—in both data sets. Trust, the top attribute in the earlier research, did not make the top five in our recent study, but psychological safety, which can be thought of as a higher bar of trust, did. Individuals may feel they can rely on one another to perform well (trust) but yet not feel comfortable being vulnerable or showing weakness (psychological safety).

The nuanced discrepancies between the two data sets are likely due, in part, to the different geographical makeup of the teams in the two articles—this article focuses primarily on Asia-based teams,[2] while the sample for the previous article was weighted more toward North America.[3] In addition, the data set here focuses solely on top teams (CEO-1), whereas the previous analysis included teams of all levels.

Our analysis suggests that key drivers of top-team performance may change over the course of the CEO tenure (exhibit). New CEOs should focus on getting role clarity right and leveraging a diverse mix of both internal and external perspectives in the early phase of building their top team. Meanwhile, mid-tenure to seasoned CEOs should prioritise innovative thinking, communication, psychological safety, and feedback. Across all tenures, purpose remains a critical factor.

Our analysis also suggests that the relative importance of core top-team attributes may shift over the course of a CEO’s tenure (see accordian “Drivers of top-team performance may evolve with CEO tenure”). For CEOs who are early in their tenure, having clear role definition and leveraging both external and internal perspectives are the standout predictors of top-team performance, while innovative thinking, communication, and psychological safety become more important as the CEO settles into the role.

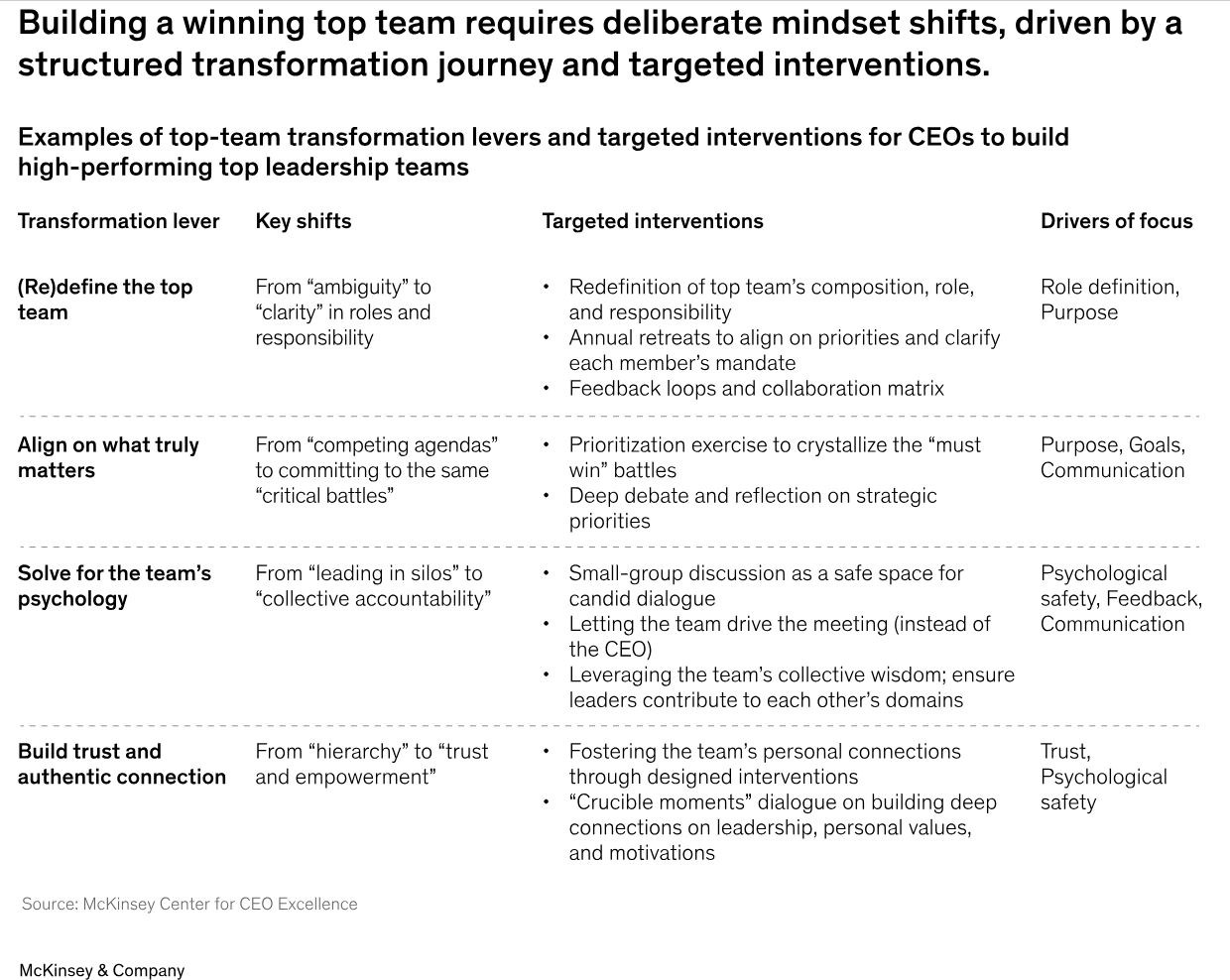

Mindset Shifts: The Power of a Top-Team Journey

Once CEOs have a clear understanding of the top team’s performance, they need to roll up their sleeves and work with the team to make the required changes. This section provides a diverse set of real-world examples to illustrate what a successful top-team transformation might look like in practice (Exhibit 4). Each of these examples focuses on a few key behaviors or attributes that were identified in the previous section as critical in driving top-team performance.

Example 1: (Re)defining the Top Team

One leading Asian pharmaceutical company lacked a clear definition and structure for the CEO’s top team. A handful of people reported directly to the CEO, but there was no real clarity on each team member’s responsibility, which prevented true accountability.

To resolve these fundamental issues, the CEO first took a step back to define what the “right team” looked like. He started by reframing the team’s purpose and composition around fundamental questions: What is the team’s mandate? Which decisions sit with this group collectively and as individuals? What roles are essential, and do we have the best-fit talent in each seat?

To ensure ongoing clarity and alignment with the chosen top team, the CEO started a tradition of annual retreats. During these sessions, leaders articulated, debated, and aligned on strategic priorities and were encouraged to thoughtfully define their individual responsibilities and mandates in relation to organisation-wide ambitions.

To foster collaboration and teamwork, a “collaboration matrix” was created to map out and identify the highest-value points of interfacing and collaboration among members of the top team. Based on this map, leaders gained clarity on critical points of collaboration and were encouraged to regularly exchange feedback to continually drive impact on joint projects.

When looking at team contribution, the CEO also realised that not all roles—or individuals—were making an equal contribution to the team’s success. He found that there were three people who set the mood for the team and were crucial in boosting overall team performance, and he therefore chose to invest heavily in these individuals. At the other end of the spectrum, he also took decisive action to remove toxic and unproductive members, or those in roles that were no longer necessary.

Clarity on “who’s in” and “what we’re here to do” is often the first and most overlooked step in top-team transformation. As a result of this exercise, the top team of this pharmaceutical company now operates with a clear structure, well-defined roles and responsibilities, and a high level of accountability, which in turn boosts both morale and the organisation’s overall performance.

Example 2: Aligning on What Truly Matters

The executive team of a regional insurance company was struggling with a common top-team issue: Leaders were juggling competing agendas and a “laundry list” of priorities—many of which they lacked the bandwidth to execute. Competing priorities among divisions led to a lack of alignment, as well as fragmented communication and execution.

As part of a broad top-team transformation, the CEO implemented a rigorous prioritisation exercise. Leaders came together to each define what success would look like for their own area in the next three years, and identify only three to five “must win” battles to get there. The exercise forced each leader to ruthlessly crystallise their laundry list of priorities into the handful that would truly move the needle. With these individual priorities on the table, leaders then engaged in a candid discussion and debate—challenging one another’s assumptions and trade-offs—to collectively distill and boil down a shared set of five collective must-win battles for the organisation.

The result was more than just a prioritised list. Through tough debates and honest reflection, the team forged a shared view of what truly mattered for the organisation—and a commitment to deliver it together. They now spoke the same language, focused their energy on the battles that mattered, and held one another accountable.

Example 3: Solving for the Team’s Psychology

A leading regional bank used to operate in a hub-and-spoke model. Top-team members worked in silos and did not have shared accountability for execution, pushing all critical decisions to the CEO.

To break this cycle, the CEO redesigned the annual planning meeting to put the top team in the driver’s seat. Each business unit head was given an uninterrupted 20-minute window to present their strategic plan, followed by five to ten minutes of clarifying questions from peers—no interruptions, no judgments, just clarifying the context. The team then divided into smaller breakout groups to delve deeper and provide feedback on one another’s plans.

For each plan that was presented, the other leaders would ask themselves a set of questions. For example: What do I like and dislike about this plan? And most importantly: What can I do to help this leader succeed?

More than a feedback exercise, this process sparked a profound mindset shift from “siloed priorities” to “collective ownership.” Leaders didn’t just critique; they committed to actively supporting one another’s success. For example, when the head of retail banking shared a plan to grow market share in one of the bank’s strategic regions, the CFO committed to provide the needed financial resources and the CMO offered to help secure a key marketing partnership in that region.

The CEO’s role evolved from directing meetings to empowering the team to lead and be held accountable. The CEO was no longer solving for all of the key decisions but stepping in to synthesise the insights and anchor alignment after all issues were actively debated and vetted by the top team.

Over time, these forums built a culture of feedback, psychological safety, and collective accountability. Leaders grew to appreciate one another’s contributions—even in disagreement. Tough, honest feedback became the norm. Top-team members started to break out of their silos as they felt more invested in and accountable for a collective set of strategic priorities.

Example 4: Building Trust and Authentic Connection

The CEO of a major Southeast Asian insurance company found that trust was thin at a time when the team was embarking on a high-stakes reconfiguration. A lack of psychological safety meant that leaders felt unable to fully surface concerns and resolve the critical underlying issues.

The CEO undertook a series of targeted interventions to work on the top team’s dynamics. One key initiative was introducing a regular forum, “Crucible Moments,” which brought team members together to share pivotal life experiences that had shaped who they had become. These were not limited to professional milestones but included deeply personal stories that revealed each team member’s fundamental values, motivations, and intent. The exercise created powerful and authentic connections among top-team members that transcended titles and roles, helping team members get to know each other at a deeper and personal level.

Trust and connection were also reinforced through small habits, such as intentionally designed in-office days to encourage in-person interaction and one-on-one lunches to create space for conversations beyond the usual agenda.

A top team can perform at its best only when trust runs deep and connections move beyond the transactional. By encouraging and actively working to build that “gel,” the CEO felt his team shift from surface-level alignment to a genuine commitment to pursuing a shared vision. Once a fundamental level of psychological safety had been established, progress in other areas—including communication, belonging, feedback, and innovative thinking—followed naturally. The aggregate result? A more cohesive leadership team.

Setting up for success: Concrete actions for CEOs

Great-performing teams are not born; they are built. A recent McKinsey study of leading athletic coaches across the United States found a common thread: In environments with razor-thin margins for error, winning sports leaders continually refine a formula for building and reinventing their teams. Success in sports is rarely about talent alone—it also comes from leaders who set clear goals and standards, assemble complementary players, and foster a culture in which the team comes before the individual.[12]

For CEOs, the same principle applies. Creating and maintaining a high-performing top team requires deliberate choices and constant investment. To avoid common pitfalls, CEOs should anchor their team transformation around the following core principles:

- Don’t skimp on the diagnosis. Many elements need to be in place to build a healthy and high-performing top team. CEOs need to take time to thoroughly understand where their teams are currently excelling and where they are not. It can be difficult for CEOs to get the perspective required to see these issues clearly. In fact, our research indicates that team leaders tend to have a more favorable perception of their teams’ effectiveness than team members themselves.[13] This mismatch is one of the reasons that an objective, empirical approach—one that brings in the perspective of all team members—and outside intervention can be valuable.

- Commit for the long haul. CEOs should make the top-team transformation a key priority and resource it accordingly. They should also view this transformation as a continuous journey rather than as a one-time fix. In our experience, the first phase of a successful top-team transformation generally takes at least multiple months, followed by an ongoing, regular program of maintenance, periodic further interventions, or both.

- And remember, practice makes perfect. While the top-team transformation may involve some one-off initiatives to fix individual issues, the core should be a strong, consistent focus on bringing the team together to build the muscle they need to work together effectively. The world’s best teams—across all fields of human endeavor—have one thing in common: They constantly practice working as one cohesive unit.

The CEO role is unique, in both its ability to shape an organisation’s fate and its accountability for the result. But no individual leader can achieve their goals alone. Building a star top team can challenge even the most seasoned leaders, particularly given that CEOs have historically found it difficult to identify the attributes and behaviors—and therefore the interventions—that can make the most difference to top-team performance.

But we now have the data to enable them to do exactly that. CEOs who are ready to invest in understanding top-team performance—and embarking on a journey to improve it—can achieve transformative results. They can turn their top team into their superpower.

Fabrice Desmarescaux is a partner in McKinsey’s Singapore office, where Gautam Kumra is a senior partner and chair of McKinsey Asia, and Joydeep Sengupta and Mukund Sridhar are senior partners. Jennifer Chiang is director of learning for the McKinsey Center for CEO Excellence and is based in the Hong Kong office.

The authors wish to thank Aleia Chavez, Archana Seshadrinathan, Blair Epstein, Carolyn Dewar, Chaitanya Parab, Cheryl Lim, Faridun Dotiwala, Harsh Nagar, Jesus Martinez, Liesje Meijknecht, Maitham Albaharna, Nakul Sharma, Ramesh Srinivasan, Trang Pham, and Xiaochen Xu for their contributions to this article.

The article was first published by McKinsey & Co.

Photo by Thirdman on Pexels.com.

5.0

5.0