We used to have just philanthropic giving, and then Corporate Social Responsibility followed by Corporate Responsibility joined. Years after, Sustainable Development Goals were introduced and business world also started to open-up to different types of sustainable investing – Socially Responsible Investment or as some call it Sustainable, Responsible and Impact investing, ESG investing, Mission related investing, etc.

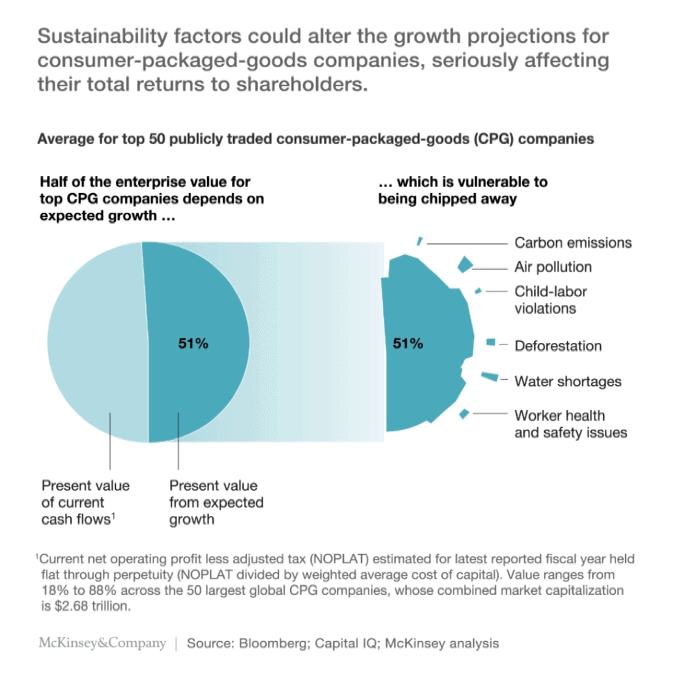

The terms, approaches and level of commitment to balance People, Planet and Profit needs have been changing, but business leaders and investors are becoming increasingly concerned that issues such as climate change, biodiversity destruction, discriminatory behaviours, income and gender inequality and many others, will in years to come pose significant challenges to companies’ long-term prospects – probably even bigger then economic growth rates. This concern is well supported by the McKinsey analysis that shows 51% of present value from expected growth is vulnerable to being chipped away due to carbon emissions, air pollution, child labour violations, deforestation, water shortages and worker health and safety issues.

According to the Harvard Business Review (January 2019) – “investors are increasingly conscious of the social and environmental consequences of the decisions that governments and companies make and they can be quick to punish companies for child labour practices, human rights abuses, negative environmental impact, poor governance, and a lack of gender equality.”

This approach, coupled with global rethinking of the role finance plays in societies give very significant role to integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria into investment screening processes and decision-making.

Globally, more than 25% of financial assets under management come with a mandate to incorporate ESG factors. However in Asia (excluding Japan), the total figure of ESG screened funds represents less than 1% of Asia’s total professionally-managed assets.

The lack of knowledge about ESG and integration of relevant sustainability practices (mostly social and environmental) as part of their core business is already identified by investors and regulatory bodies as one of the key corporate vulnerabilities in Asia – the problem that if not adequately addressed will in years to come significantly decrease profit of Asian companies.

ESG, Board level commitment and governance structure – what can go wrong?

Various research and analysis have proven that Board level commitment is crucial in ensuring that ESG criteria are taken seriously – that sustainability is embedded across the organisation and that adequate policies, procedures and resources are available for implementation of sustainability practices.

But what happens if Board is not on board? What happens when sustainability matters are not identified and assessed, or not adequately addressed by the Board and relevant governance structure?

There are many things that can happen, from shaming the company through traditional and social media, to losing of customers and partners, to disruption in supply chain, to breaking of contracts and to partial divestments – all of which will negatively affect company’s reputation and consequently lead to significant financial loses.

However, in recent years more and more national and international law firms that are specialized in violation of environmental and social rights, proactively started launching lawsuits against companies (their Boards and CEOs as well) and local governments. They also watchdog insurance companies and put pressure on their governance structures and decisions. By doing all this they are rather loudly and transparently influencing various investor’s decisions.

Following are just few environmental and social (ES) cases caused by bad governance (G) decisions. These cases cut across:

- national and international courts of justice;

- developed, developing and under-developed countries; and

- different industries

Lawsuit against Companies (E in ESG) – Belchatow power plant in Poland is the single largest greenhouse gas emitter in Europe (coal plant) and a major contributor to climate change. In September 2019, ClientEarth law firm from UK launched a lawsuit to demand it stops burning coal – or take measures to eliminate its CO2 emissions – by 2035 at the latest.

Lawsuit against Local Authorities (E in ESG) – Environmental lawyers are putting 100 local authorities across England on notice, warning them that legal charges will be pressed against them if they continue to violate their legal obligations and if they do not introduce proper climate change plans.

Monitoring and putting pressure on insurers (E and S in ESG) – Climate finance lawyers have monitored work of Lloyd’s of London (insurance and reinsurance market) and after noticing that the insurer was underwriting the Carmichael coal mine (Australia, Central Queensland), they put them on notice of legal and financial risks associated with this controversial decision. Faced with this pressure, Lloyd’s announced it would implement a ‘coal exclusion policy’ but never made the criteria publicly available. Lawyers are now (summer 2019) calling on Lloyd’s to publicly:

- confirm the criteria and implementation of its coal exclusion policy;

- confirm steps that have been taken to manage coal-related risks; and

- present its position on the underwriting of the Carmichael coal mine by its syndicates.

International claims – community (S in ESG) – In December 2014, Martyn Day and his team achieved a landmark settlement for over 15,000 Nigerian fisher folks following two oil spills from a Shell pipeline (in 2008 and 2009) that devastated their Bodo community. In the aftermath of the spills, Shell originally offered £4,000 (four thousand pounds GBP) compensation to the entire Bodo community before the villagers sought legal representation from lawyers in London. Leigh Day law firm began legal action at the High Court in March 2012 and in 2014 instead of initially offered £4,000, Shell paid £55 million – £35m for the individuals and £20m for the community.

International claims – safety (S in ESG) – The ethnic violence broke out in Kenya in December 2007. Large groups of attackers invaded Unilever’s Tea Plantation in Kericho resulting in 7 victims being brutally killed, 56 women raped and many others who were subjected to serious physical attacks. The Kenyans claim that Unilever failed to take appropriate steps to protect them from the foreseeable risk of violence whilst taking steps to protect management housing and company assets. Instead of helping these victims, Unilever has fought hard to prevent the claims from proceeding in the English courts, in the knowledge that the case cannot proceed in Kenya and thus deny them any access to remedy. Legal process against Unilever is still on-going.

International claims – modern slavery (S in ESG) – In April 2019 the High Court of UK has ruled in favour of a group of Lithuanian men who were put to work in terrible conditions by a British company DJ Houghton Catching Services. The Court found the workers were obliged to work shifts without respite, sleeping in the back of a mini bus between farms, and worked massively more hours than the entirely fictional number of hours recorded on their payslips. The Court also ruled that Mr Houghton and Ms Judge (CEO and CoSec) were personally liable to the workers for the serious contractual and statutory breaches of their company.

These few briefly described cases show not just that understanding of ESG criteria and their importance is crucial for business, but that more and more cases of ESG violation have been monitored and adequately addressed through lawsuits that are launched at national or international courts.

It is very clear that this trend will not stop because more and more people are becoming aware that companies should be responsible for their impacts on environmental and social systems in which they operate. Increasing number of people understand that environmental sustainability (E) covers air, water, energy, biodiversity, waste and that these resources should be protected in each community and country. Fortunately, increasing number of people also understand that social sustainability (S) is not typical feel-good CSR or charity type of programme but it actually covers fair labour practices, health and safety, human rights (child labour, slavery), diversity, equality, training and education, community engagement, anti-corruption and product responsibility.

Consequently more and more Board members across the world start to understand that if they are not on board, if they continue to ignore ESG criteria and turn the blind eye on unsustainable practices someone, either in their own country or from abroad, will rather soon call for their responsibility.

You might think that above presented cases are too far away from Asia or Malaysia, but you might be wrong. If one email from an ordinary fisherman in Nigeria to Leigh Day law firm in UK in which he explained how oil spill negatively influenced health and livelihood of his community ended up by getting £55 million of compensation, then think twice before you conclude that ESG criteria are not priority for your company and that regarding sustainability issues your Board is doing just fine.

This article was written by Dr. Jasmina Kuka, CEO of W!SE – Working on Impact and Social Empowerment, www.wise-a.com

Photo by Scott Webb on Unsplash.

4.8

4.8