What defines top-performing boards? Our second Board Culture and Director Behaviors Survey completed by 750 corporate (supervisory board-level) directors of large public companies worldwide provides a roadmap for driving improvement in board effectiveness and, potentially, corporate performance.

Based on our experience working with hundreds of boards each year, we know board and director performance depends on the quality of board leadership, the ability of the board to focus on the right issues and a small number of critical director behaviors. Our latest research backs this up.

The link between critical director behaviors and higher company performance was evidenced in our second Global Board Culture and Director Behaviors Survey, completed by 750 corporate (supervisory board-level) directors of large public companies worldwide. This data provides a roadmap for driving improvement in board effectiveness and, potentially, corporate performance.

This year’s report focuses on understanding a group of boards we call “Gold Medal Boards”—those that rate themselves as operating in a highly effective manner and that oversee a high-performing company (one that has outperformed relevant total shareholder return (TSR) benchmarks for two or more years consecutively). When we look at the data for this group and compare it to the broader population of boards, the differences are clear. These boards spend the same amount of time on their work as the global peer set, but prioritize more strategic, longer-term and forward-looking discussions. Their directors are more likely to seek to understand other perspectives, focus on being present at meetings and build deep relationships with management and investors. Gold Medal Board chairs lead differently too—demonstrating behaviors that foster and facilitate higher-quality debates in the boardroom.

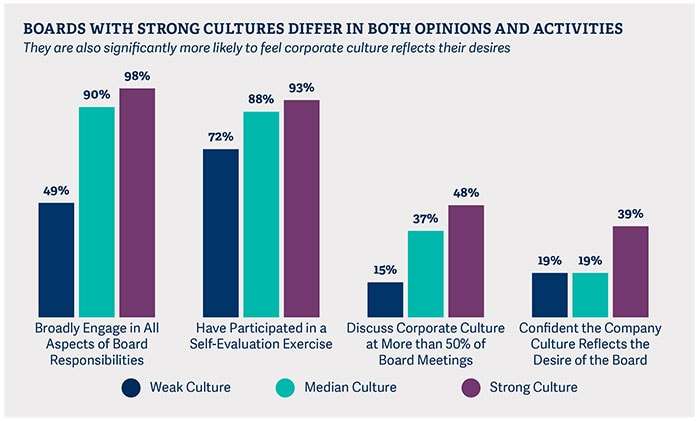

Along with Gold Medal Boards, we also report on board members who self-identified as having the most engaging, professional and productive cultures and who seek to understand what sets them apart and what other directors can learn from them. Directors on boards with a strong positive culture are more likely to report that their fellow directors broadly engage in all aspects of board responsibilities, that they have participated in a self-evaluation exercise, that they discuss corporate culture at more than half of all board meetings, and that they are confident the company culture reflects the desire of the board – an interesting correlation at a time when there is increasing pressure for directors to oversee corporate culture, including diversity and inclusion.

Our 2019 Global Board Culture and Director Behaviors Study concludes with a set of recommendations for directors and board leaders who want to take action on these insights.

The Gold Medalists: High-Performance Companies with Highly Effective Boards

The average director in our study spent 200 hours a year on board activities (excluding travel) per company, but not all directors spend those hours the same way. In fact, while most directors in this year’s study report focusing on the basic requirements of board service, others reported acting in a different way—and getting vastly different results. These directors serve on the boards of high-performing companies and also identify their board as operating in a highly effective manner. The intersection is a group of distinctive boards we call Gold Medal Boards.

How are they different? First, directors of Gold Medal Boards report focusing their time on a different set of activities than their peers at other large companies: having conversations and undertaking work related to more strategic issues.

High-Performance Companies: Companies that exceeded total shareholder return (TSR) compared to relevant benchmarks for two or more years in a row.

Gold Medal Boards spend more time on forward-looking, value-creating activities and less time on compliance activities than their fellow directors on other boards. In our survey, they were more likely to identify strategic planning, oversight of M&A transactions and CEO succession planning among the top three areas where they spent the most amount of their time in the prior 12 months. Directors also were more likely to report engaging in enterprise risk review, board refreshment activities and crisis management scenario planning.

Gold Medal Board directors were less likely than our sample of all boards to spend time on lengthy financial statement reviews, audit-related activities and compliance-related activities—although all those activities get done too. “Many times, it seems boards spend too much time on operational performance versus strategic issues,” one director wrote in the survey this year. “We eat what we are fed.”

Are these Gold Medal Board directors simply grinding through their work, accomplishing a lot but at the expense of teamwork and quality relationships? It doesn’t seem so. Directors on Gold Medal Boards report significantly higher satisfaction levels with their board culture. Ninety-eight percent of these directors rated their boards as being a 9 or 10 on board culture on a 1–10 scale, over twice the frequency at which the global peer set rated their board culture.

Behaviors and Qualities of the Most-Effective Directors

Just focusing on the right activities isn’t enough to make a Gold Medal Board. “A dysfunctional board can kill a company,” one director reminded us. The individual directors selected for the board matter. They need the right skills and experiences based on a company’s strategy, organizational complexity and industry. Finding the right mix is crucial. But once they are on the board, the way they behave is just as important if they are to contribute meaningfully.

Our research identified distinct director behavioral characteristics that contribute to the likelihood that a board will achieve Gold Medal status.

Directors on Gold Medal Boards are open-minded but focused: They want to hear a multitude of viewpoints and conflicting opinions, but they engage with those voices in a productive manner that is focused on finding the common ground and working toward an actionable conclusion. Possessing independent perspectives while avoiding groupthink is an important driver leading to Gold Medal Board status.

What else matters? If non-executive directors seek to understand other perspectives while communicating, rather than making assumptions about people and positions, and if they focus on being present and engaging in the moment, the board is much more likely to become a Gold Medal Board. “Engaged directors who are willing to spend the time and are willing to focus are better than highly qualified or reputed members who are not engaged,” noted one director.

Additionally, these directors are mindful of the importance of hearing multiple perspectives in board discussions and building strong relationships inside and outside the boardroom. These relationships matter. In fact, shareholder engagement (cultivating relationships with investors) directly impacts whether a board is likely to be a Gold Medal Board.

The Board Chair—Leading the Way

While all directors can contribute to the board’s success, the board chair has a unique set of responsibilities, both in the tone that he or she sets and for how time and resources are deployed.

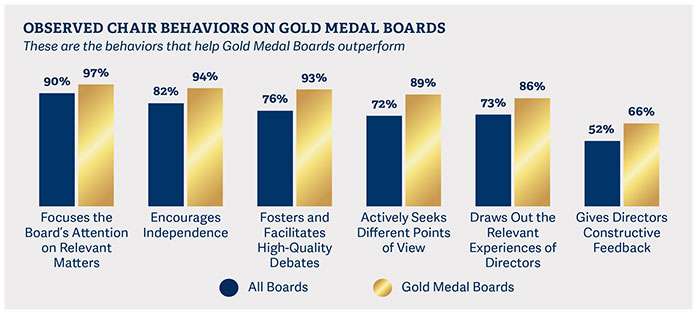

Gold Medal Board directors are more likely to report that their board chair focuses the board’s attention on relevant matters, encourages independence, and fosters and facilitates high-quality debates. We have found that the strongest chairs are great facilitators; they get the best out of the board as a collective group as well as out of individual directors. These board chair behaviors result in the board being 14.4 percent more likely to earn Gold Medal Board status.

Great chairs also work to create a sense of mutual respect among board members, which one director identified as “critical to optimizing board performance.” And it avoids a problem that is all too common in many boardrooms: “There are many instances where the loudest or most aggressive voice prevails,” noted one director, “but that does not foster an inclusive discussion.”

Components to Build a Strong Board Culture

In our work with boards, most directors we meet will talk about their unique board culture and the importance of finding directors who will fit in. When directors define that board culture it often revolves around “collegiality” and “respect.” Our research now provides a more compelling characterization of a strong board culture.

Boards with the self-identified strongest cultures behave differently from those with weaker cultures, a result of director behaviors, board chair leadership and purposeful decisions about how the board spends its time and energy.

There was a statistically significant difference between boards with strong cultures and those with weak cultures across nearly every observed behavior. Interestingly for those advocating for improved board oversight of corporate culture, boards with strong cultures spend more time discussing corporate culture as a regular part of their agenda and are more confident that the corporate culture reflects the desires of the board.

What Other Behaviors Contribute to a Strong Board Culture?

Building a positive, engaging board culture takes work and is the combination of numerous director behaviors. Our research and experience demonstrate that they do not just happen, but rather occur as a result of a group of directors intentionally focused on building a positive culture. According to our survey results, directors on boards with strong cultures work to build and demonstrate trust with their peers. They are more open-minded but focused, staying on the matter at hand and eliminating tangents. And they are open to new ideas and ways of doing things.

On boards with strong cultures, directors are deliberate and thoughtful, and they are more likely to constructively challenge executives when appropriate, but are careful to avoid crossing the line from oversight into operations and management. They do this while striving to establish and strengthen relationships with senior executives beyond the CEO. These directors gain a strong understanding of the executive talent in the succession pipeline while also gaining greater exposure to the company’s business and culture.

Not surprisingly, the board chair plays a role in establishing and maintaining a strong board culture, leading the board and facilitating debates. These chairs work to draw out the relevant expertise of individual directors and ensure that the board is conducting robust self-evaluations.

What Stayed the Same? The Behaviors That Drive Board Effectiveness

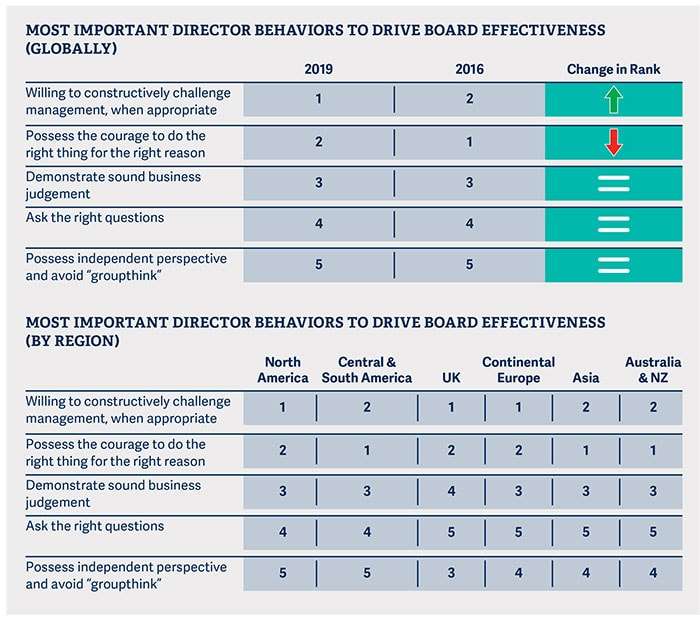

When we conducted our first Global Board Culture and Director Behaviors Survey in 2016, we asked directors to identify their top aspirational behaviors for fellow board directors. The five critical behaviors from 2016 were reinforced this year.

Despite having twice as many respondents (750) this time, the only difference is that the first two behaviors flipped their order of priority—a remarkably small change that only serves to reaffirm the importance of these five critical behaviors in the boardroom. The same five behaviors are consistent across more than 20 countries with different national cultures and corporate governance systems. We will examine this in more detail in future publications and events.

Methodology

The Global Board Culture and Director Behaviors Survey and subsequent data analysis was conducted from October 2018 to February 2019. Over 750 supervisory board-level directors from more than 20 countries participated in the survey. The companies on whose boards they sit span all industries, and the median company revenue fell in the range of $2–$10 billion. The survey asked over 25 questions focused on board culture, director behaviors and board effectiveness.

We asked additional questions to participants using a 1–5 scale to rate how often they observe particular behaviors among their fellow directors on the largest public company board on which they serve. We also asked directors additional questions to rate the effectiveness of that board, its chair and its culture. From these ratings, boards were classified as least effective (0–6 on a 10-point scale), moderately effective (7–8) or most effective (9–10). We also asked directors to identify whether their company exceeded their relevant benchmark TSR for two consecutive years in order to determine if the company was high performing against its competitors.

Additionally, we then asked directors to rate/rank the most and least important behaviors for driving board culture and effectiveness, using a survey methodology that forces participants to make trade- offs between multiple high-value options (with the assumption that integrity was a foundational behavior for any director). This resulted in a weighted score of the importance of each behavior relative to the others.

AUTHORS

RUSTY O’KELLEY III is a senior member of Russell Reynolds Board and CEO Advisory Partners and the global leader of the Board Advisory and Effectiveness Practice. He is based in New York.

ANTHONY GOODMAN is a member of Russell Reynolds Board and CEO Advisory Partners. He is based in Boston.

ANA-LISA JONES leads the Board & CEO knowledge team at Russell Reynolds Associates. She is based in Boston.

PJ NEAL manages the Center for Leadership Insight at Russell Reynolds Associates. He is based in Boston.

5.0

5.0