At a recent board meeting, the CIO of a major global corporation led a wide-ranging discussion about the tools and practices needed to fortify the company’s data and systems against breaches. The board encouraged heightened investment and vigilance, then moved on to its next agenda item, a financial committee presentation leading to a board vote on acquiring shares to consolidate ownership in an enterprise in which the company held a minority stake. To the surprise of the CIO, who was still in the room, there was no discussion of cybersecurity, even though the acquiree was operating in a region where cyberbreaches and criminal hacking were endemic. Happily, the CIO’s fortuitous presence enabled a proper discussion of the impact of the decision on the company’s cyber risk profile, and a change in the acquisition approach aimed at bringing the acquiree more fully into the corporation’s IT and operational infrastructure.

The board had not connected the dots between the two agenda items because its view of cybersecurity, as well as the CEO’s, was more focused on risk dashboards and surveillance than on the security implications of business decisions. It’s an issue we’ve seen variations on for years. Simply put, far too many boards and CEOs see cybersecurity as a set of technical initiatives and edicts that are the domain of the CIO, chief security officer and other technical practitioners. In doing so, they overlook the perils of corporate complexity—and the power of simplicity—when it comes to cyber risk. We’d propose, in fact, that leaders who are serious about cybersecurity need to translate simplicity and complexity reduction into business priorities that enter into the strategic dialogue of the board, CEO and the rest of the C-suite.

Questions such as the following can help catalyse this conversation:

- How does a full accounting of cyber risk affect our business model’s attractiveness, and does that suggest the need for a “simplification agenda”?

- How transparent are the cyber risks and trade-offs associated with our external partnerships, and what would be the pros and cons of simplifying our ecosystem to make them more manageable?

- How risky are our IT-enabled legacy processes, and how should we prioritise investments to secure, simplify and transform them to achieve competitive advantage?

Leadership teams who grapple with questions like these and embrace simplicity boost their odds of making the entire enterprise securable.

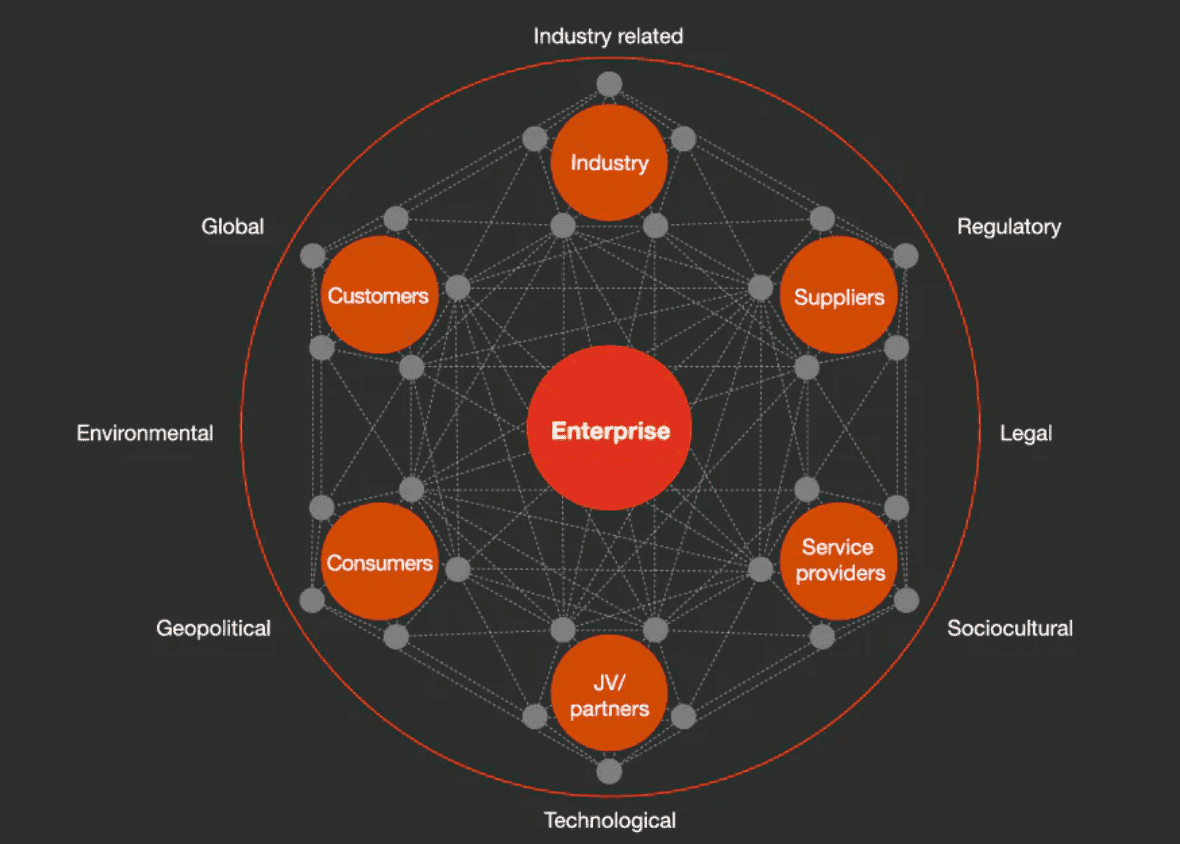

In today’s hyperconnected world, companies need to consider multiple areas of cyber risk throughout their ecosystem.

A network of digital interconnectedness

Creeping complexity

Even a decade or so ago, the technical operations, systems and footprints of many large companies had become extremely costly and complex. Breakneck digitisation in the smartphone era has exacerbated matters, as companies have increasingly created ecosystems with a variety of new partners to help expand their reach and capture new, profitable growth. They range from supply chain relationships across goods and services (including IT services) to partnerships for data, distribution, marketing and innovation. Even more recently, the business challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic have spurred faster adoption of digital solutions that rely on data, digital networks and devices that are most often operated by companies outside the organisation’s borders.

The technology architecture of many organisations, often made up of layers of legacy systems with multiple constraints on their flexibility, represents an ever expanding dimension of complexity. (By contrast, many “digital native” companies of more recent vintage have a simplicity advantage. These companies are built digital from the ground-up, using more recent generations of IT, standards and techniques meant to create increased interoperability across systems.) Legacy structures are often riddled with open seams and soft connections that can be exploited by attackers, whose capacity to infiltrate sprawling systems has grown. The pressures on these legacy structures have intensified as companies have pushed their current IT to keep pace with the digital natives. Mergers often multiply risks, by connecting already complex networks of systems, which makes them exponentially more complex.

As a result, complexity has driven cyber risks and costs to dangerous new heights. The numbers of significant cyberattacks globally are increasing and include potentially devastating criminal “ransomware” attacks and nation-state activity targeting government agencies, defense and high-tech systems by, for example, breaching IT network-management software and other suppliers. Each major incident exposes thousands of users (at both companies and government agencies) to risk, and can go undiscovered for months.

Thinking about the trade-offs

As senior leaders revisit their growth strategies in the wake of the pandemic, it’s a good time to assess where they are on the cyber-risk spectrum, and how significant the costs of complexity have become. Although these will vary across business units, industries and geographies, leaders need good mental models for self-assessing the complexity of business arrangements, operations and IT.

One conceptual framework for thinking about complexity and the cyber-risk spectrum is the Coase Theorem, formulated by Nobel Prize winner Ronald Coase. He posited that companies should use external contractors to supply goods and services until the transaction or complexity costs associated with those arrangements exceed the coordination costs of doing the work in-house. A similar dynamic may be at play in cyber-risk assessment. Cyber risk (whether generated through a supplier relationship or customer relationship or internal arrangements) is a sort of “external” cost—one that has risen as cyber attackers get better and become more pervasive. At the same time, the “transaction” costs within the enterprise of establishing multiple nodes of partnerships (where risks are hidden) have actually gone down, thanks to the ubiquity and lower cost of digital interactions. The upshot: a new environment where the costs of failure have risen markedly while the costs of creating complexity have gone way down.

Tackling complexity in three areas

Leaders seeking to strike a better balance can start with some basic principles. One is ensuring that strategic moves won’t increase complexity risk and make the current situation worse. Another is understanding that simplification of company IT may require more than minor rewiring of systems, and instead may demand more fundamental—and often longer term—modification to IT structures, to make them fit for growth. In our experience, the challenges and opportunities fall into three areas.

- Business models.

We have seen that companies often respond to breakdowns in cybersecurity with a nod to their gravity, but take actions that are narrowly focused and which are ultimately patches on a broken process. The new intensity of threats, however, often requires rethinking at a higher level: coming to grips with problems and risks enmeshed with business models. At one company we know (and the situation isn’t atypical), there were high levels of autonomy in most things digital. Regional and business unit leaders had nearly a free hand in choosing digital partners, deciding on systems and networks for customers, suppliers and more. After a minor cyber-attack in one region, IT leaders attempted to provide all geographic areas with guidelines and best practices for reducing risks, including rules for selecting partners and suppliers. They found, however, that the proposed mandates were beyond IT’s scope. The new approach required the CEO to modify what was, in effect, an element of the company’s business model: the freedom granted business unit executives, which had enormous implications for digital complexity and cybersecurity. - External partners.

More typical are challenges involving ecosystems and supply chains—whose opaque complexity has outstripped efforts to manage them securely. When a new operations director took charge of the function at one global retail organisation, she was alarmed to find customer data potentially at risk from what she termed “a chaotic supplier arrangement.” In one instance, her predecessor had engaged six different vendors to manage customer contacts as the company’s mix of customers and product lines shifted over time, and it entered new markets. Two of the vendors had histories of data breaches, so the operations director felt action was needed. With input from the CEO and board, she reduced the number of vendors to two of the most capable and innovative players in the industry, thus allowing for both diversity and resilience that built trust. The reduced complexity allowed for greater transparency, which enabled all parties to better understand their individual roles in protecting their supply chains from cyber disruptions. Senior leaders signed off on a backup system for all customer data, as well as new guardrails for access to customer information. The operations director added key positions to her own staff to keep a closer watch on vendor security practices. Ultimately, the customer-data ecosystem became more securable, with the company having a firmer handle on its own and its vendors’ responsibilities, a better demarcation of individual accountabilities, and new technologies for increased monitoring. - Internal systems.

In-house processes and systems are likely to require a close inspection for the complexity and risks they harbor. A case in point: at many financial institutions, payment systems have been built over several years with a combination of recent and legacy applications. Outages that knock out system availability (sometimes leaving customers unable to complete transactions for several days) are often linked to legacy technology in core payment systems. In truth, the cause often isn’t necessarily the nature of the older technology itself, but rather the outdated processes it supports. Traditionally, these processes have been structured to close transactions over a multiday payment cycle. As business has moved to a demand for real-time completion of transactions, ever-more complex workarounds have had to be built into legacy systems, with technology that back-fits “instant” payment into the multiday process. This complexity has led to an increased likelihood both of major failures and of smaller breakdowns cascading into significant incidents.1 Replacing these systems requires tough business decisions, sizeable investments and the will to overcome an attitude of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” The rising costs of complexity may shift the balance.

Although the benefits of simplification are large, extending far beyond cybersecurity, we’re under no illusion that they are easy to realise. Reducing complexity while establishing a framework for governance and shared responsibility demands deliberate action, over the long and the short term. It also demands the attention and energy of CEOs and boards who understand its value, and are ready to invest in changing mindsets, across the management team, about the benefits of simplicity. Leaders who are ready to step up and set the tone will create a better blueprint for a securable enterprise.

- Richard Horne is a recognised leader in the field of cybersecurity and has advised governments, companies, law enforcement and regulators globally. He serves as chair of the UK cybersecurity practice. Based in London, he is a partner with PwC UK.

- Sean Joyce is the global and US leader for cybersecurity and privacy at PwC. He helps scale the firm’s cyber offerings worldwide, and advises on digital threats, best practices in risk and how to use cybersecurity as a business enabler. Based in Virginia, he is a principal with PwC US.

PwC US director Michael Versace also contributed to this article.

1. Complexity and “close coupling” are often the drivers of catastrophic events, from airline crashes to nuclear power plant failures. A wealth of academic research has been done on breakdowns that cascade into wide-ranging failure.

5.0

5.0