The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance article, “Why ExxonMobil’s Proxy Contest Loss is a Wakeup Call for all Boards,” was written by Russell Reynolds Associates Consultant Rusty O’Kelley and Senior Board Advisory Specialist Andrew Droste, based on the paper, “Where was the Canary in the Boardroom? Why ExxonMobil’s Proxy Contest Loss is a Wakeup Call for all Boards.” The article is excerpted below.

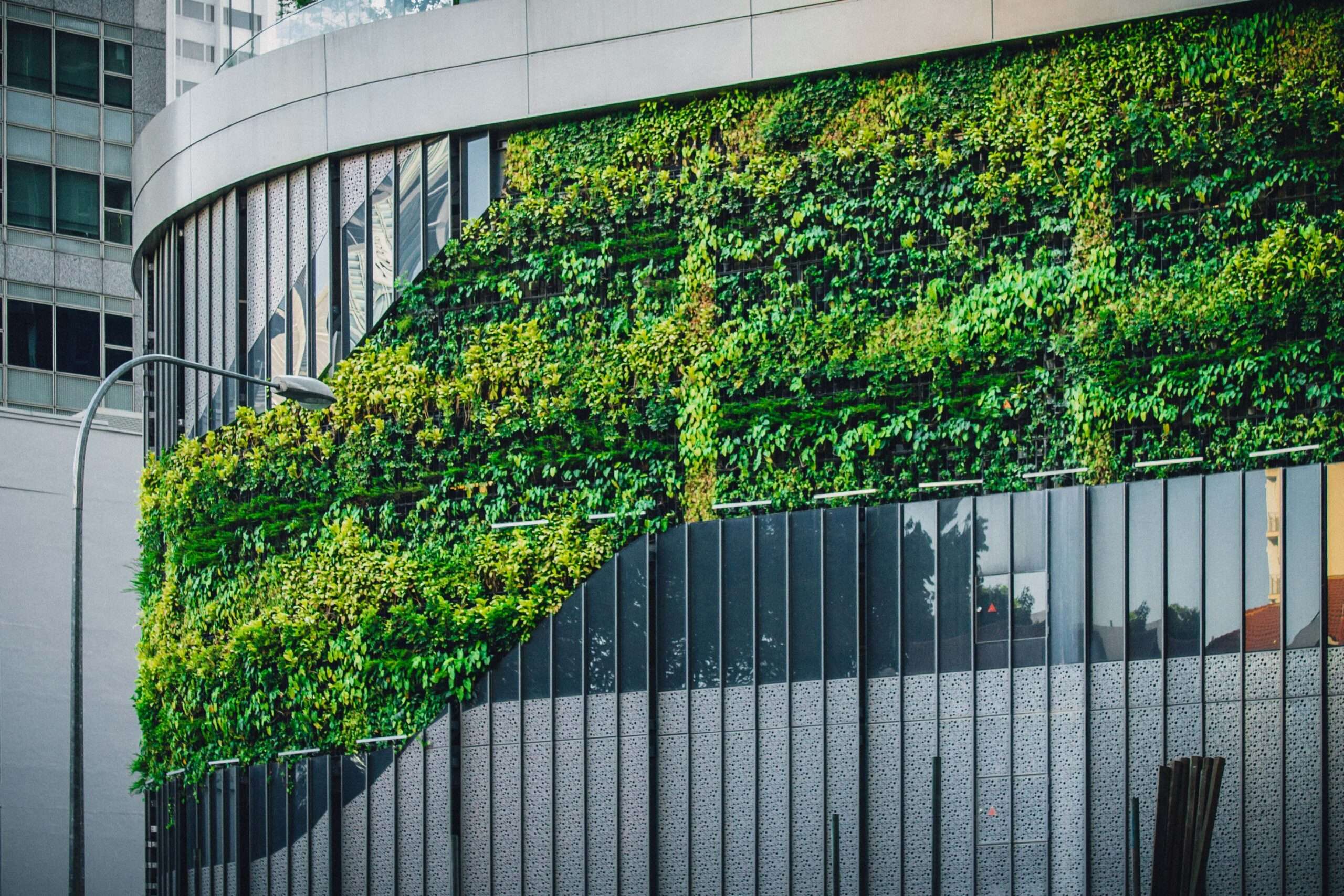

Over the past five years, the largest institutional investors have been increasingly vocal and specific about their expectations of boards and directors regarding board composition and ESG. Despite this, they have rarely acted on those concerns when it comes to director voting. However, the ExxonMobil proxy fight may be a sign things have changed. Twenty twenty-one will go down as the year that large institutional investors aligned their voting with market communications and voted out three sitting board members at ExxonMobil. The world’s largest shareholders have now demonstrated that they are willing to act and that they expect executives to take action on ESG and climate change. Importantly, this is a lesson that board composition matters and director skills need to align with a company’s strategy.

At the end of May, the US proxy season reached its apex and the long-awaited contest between ExxonMobil and Engine No. 1 came to a vote. Engine No. 1, an activist hedge fund with just .02% ownership in the company, argued throughout the contest that there were shortcomings in oil and gas experience on ExxonMobil’s board, slow strategic transitioning to a low carbon economy, and historic underperformance and overleverage relative to peers. The fund proffered four board director candidates to ExxonMobil investors, three of whom were ultimately elected to the 12-member board—and as a result, three sitting board members were ousted.

While this specific vote surprised many people, the increasing focus on ESG should not.

As we do at the close of each year, Russell Reynolds Associates interviewed over 40 global institutional and activist investors, pension fund managers, proxy advisors and other corporate governance professionals in late 2020 to identify the governance trends most relevant to boards. Atop our 2021 list was Climate Change Risk, and not far below it Return of Activism. In each of the prior three years, ESG topics consistently made their way onto the list. However, this was the first year climate took the top spot. Many savvy governance observers were paying close attention to how Exxon’s top three investors—Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street, in that order—voted. The Big Three, which own roughly twenty percent of the S&P 500’s outstanding shares, had made significant climate commitments over the past several years. The key question for many was whether these commitments would translate into votes. In the end, BlackRock supported three dissident candidates and Vanguard and State Street each supported two.

The ExxonMobil contest was the result of the Climate Change Risk and Return of Activism trends intersecting and more than a decade of underperformance against their peers. We expect these trends to continue, and advise boards to consider the following key learnings and recommendations:

1. Boards must be proactive in assessing board skills and risk generally. In the Exxon contest, it is important to note, Engine No. 1 was not looking to add “ESG expertise” to the Exxon board. The first pillar of their campaign to restore value creation stated: “Board Composition—four new independent directors with successful track records in energy.” What the Exxon contest underscored was that relevant operational industry expertise is essential to an investor’s board quality calculus. Boards must consistently ensure their composition aligns with relevant industry risks and strategic opportunities. As one of the world’s largest investors said to Russell Reynolds: “We always ask, is this board fit for purpose in terms of assessing risk and providing the oversight of the execution of the strategy?” Three of the four nominees had oil and gas experience—Engine No. 1’s chief argument for soliciting change at the top. As one of the largest investors noted to us, “ultimately, this was a board composition issue” and the board could have solved for the “G” in ESG prior to the proxy contest, thus taking away the dissident’s most compelling claim. Moreover, Exxon’s sluggish transition to a low carbon economy was evident via public disclosure relative to peer O&G companies like Eni, Total, BP, and Shell. These “E” concerns are no longer simply niche, activist concerns— they are materially important to many investors when assessing whether the board is equipped to oversee management.

To read the full article, click here.

5.0

5.0