By Jonathan Cherry

Let’s have a closer look at their strategy to figure it out.

The warm marketing glow that at one point seemed to beam so brightly on the Peloton brand – has faded significantly.

For those who don’t know, Peloton is a high-tech fitness company that sells extremely expensive stationary exercise bikes that are connected to live spinning classes via the net, which are offered to paying customers courtesy of a monthly subscription fee.

The brand is considered to be super premium and is aimed at a very wealthy clientele.

Since the later part of 2021 however, a dark cloud of doom has blanketed the US-based ‘fitness disruptor’, once touted as one of the most innovative companies in the world by journalists and clever people who love to create rankings.

In pure dollar terms, the Peloton stock price has fallen off a cliff; going from a high of $162.72 in December 2020 to just over $20 today.

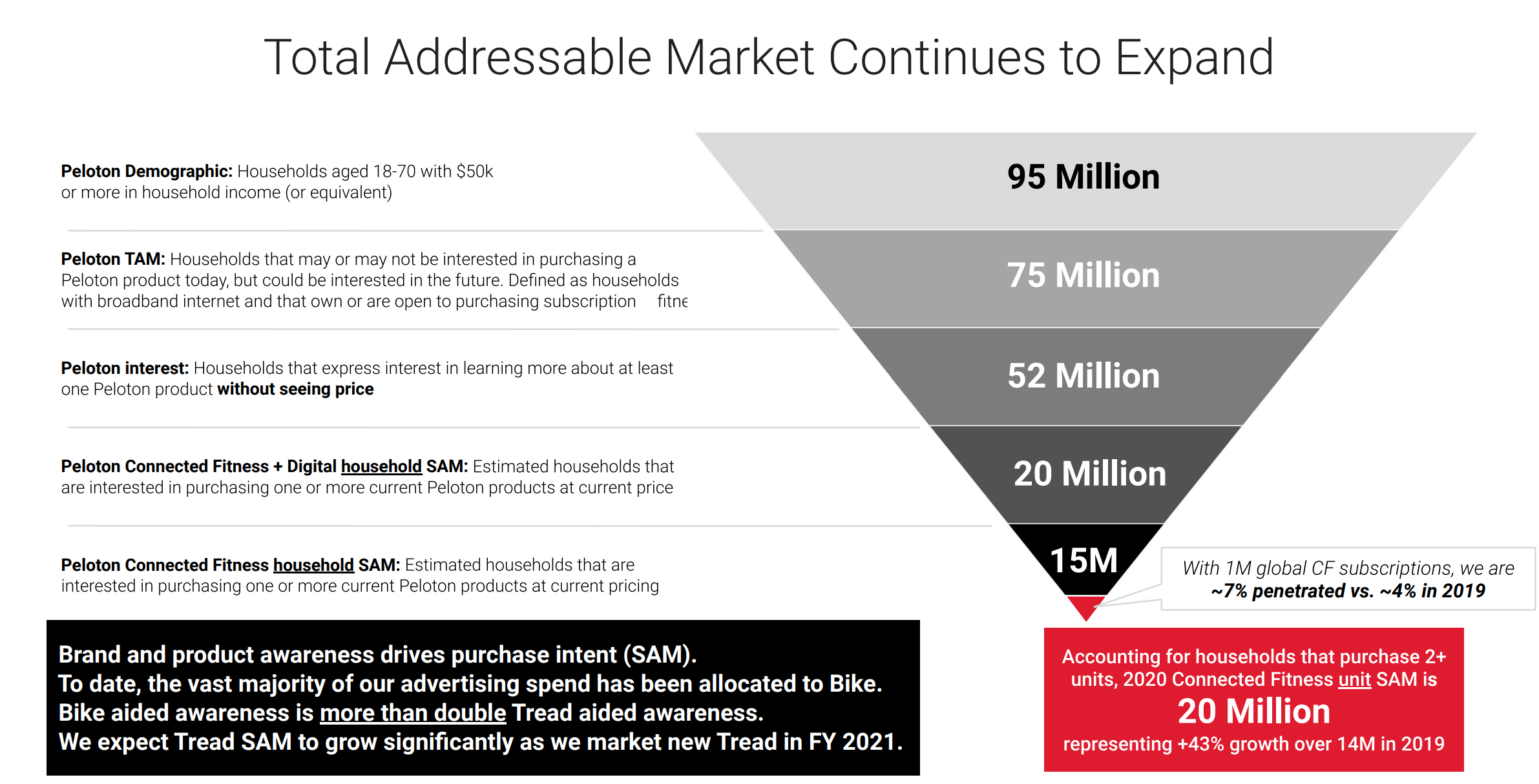

For a business, that only 18-months ago had the BHAG (Big Hairy Audacious Goal) of securing 100 million subscribers (Peloton had 2.49 million subscribers in September 2021) judging by current performance, that goal now seems totally unattainable in the opinion of the market.

So what went wrong?

If Peloton was / is a great case study in how to build up a great community-fuelled brand; what lessons can be drawn from its apparent failure to deliver on its bold plan?

Firstly, let’s have a careful look at their last publicly-published strategy.

Their Business Model

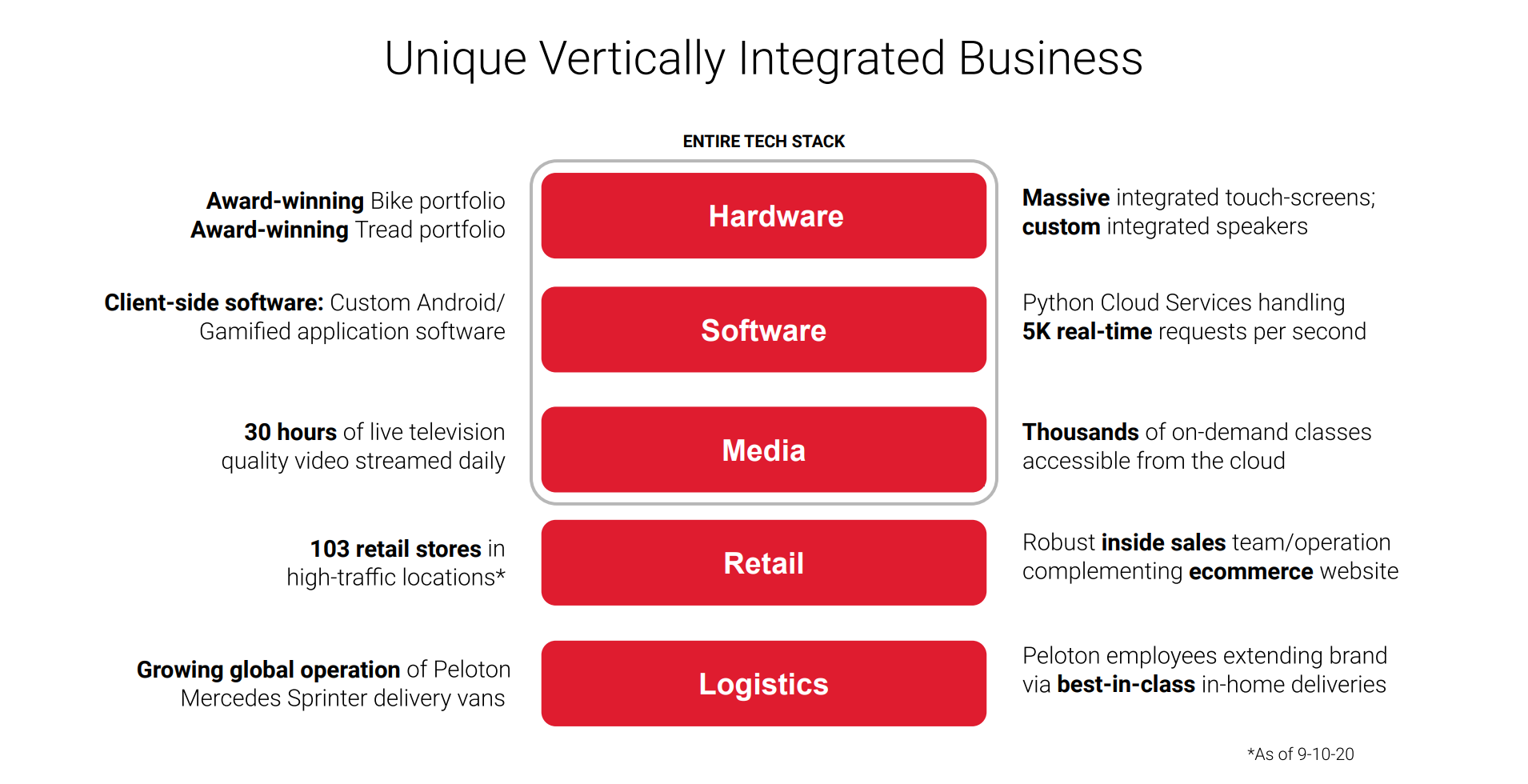

Much like Tesla’s strategy, Peloton chose to own and develop their entire value chain.

They designed and built pretty much everything themselves: their own stationary bike, the software, the content, they ran the retail outlets that sold the bikes…they even handled their own deliveries.

Unlike Tesla however, there is nothing definably unique or completely revolutionary about their product offering. They are not building a ‘never seen before’ electric car where there simply are no recognisable suppliers in the marketplace.

You can’t point at it and say that they are reinventing exercise itself, which would give them a plausible reason as to why they need to take complete control of every aspect of the value chain. There are already companies that make better stationary bikes, better software, better deliveries – so perhaps partnering with them, instead of trying to do what they do best, would have been a better move. Why completely own a business process if there is no strategically sound reason to do so?

By choosing to own every part of the value chain, Peloton was forced to charge very high prices for their equipment (the bike costs $1895.00 – $2495.00) and compel users to then only use their content and software.

This made the brand and the product highly exclusive and for a start-up it limits their scope for huge growth numbers significantly.

When investors, who thought that they were buying into a high-growth stock (because financially they are currently generating a net loss of $313.2 million a year), started to nudge the company about growth, they then flip-flopped all over the show with their pricing. Dropping the pricing at first of their treadmills and bikes and then raising it again when they realised they were diluting their brand and its appeal to their core market.

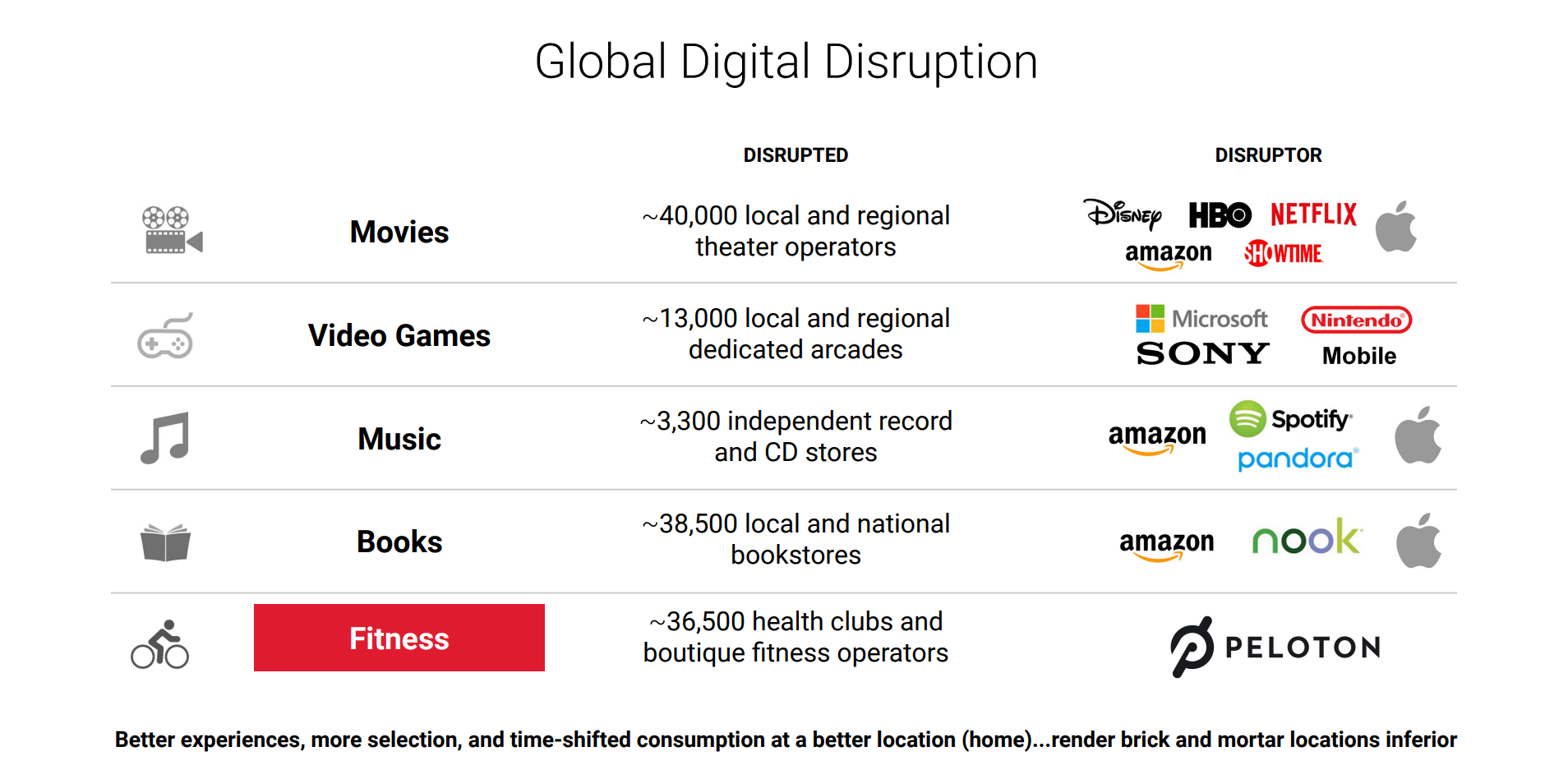

Misunderstanding Digital Disruption

This slide above is some strong evidence that Peloton didn’t actually understand the concept of disruptive innovation. This BTW is not unusual – disruption is one of the most widely misunderstood and misused business terms around the world.

‘Disruptive Innovations are NOT breakthrough technologies that make good products better; rather they are innovations that make products and services more accessible and affordable, thereby making them available to a larger population.’

All the brands listed as disruptors in this image opened up the marketplace by making their business category more accessible and cheaper thanks to technology and innovation, attracting more customers into the marketplace.

Offering an exercise service that is far more expensive than existing health and fitness options is not going to disrupt the category; you may sign up subscribers at first thanks to hype and lots of positive PR, but the Peloton idea is not one that radically redefines how the category has traditionally been serviced.

Accuracy here matters a lot, because strategically the business would have been measuring itself against a set of growth criteria which is just not relevant to the business that Peloton actually finds themselves in.

Failure to Read the External Signals Properly

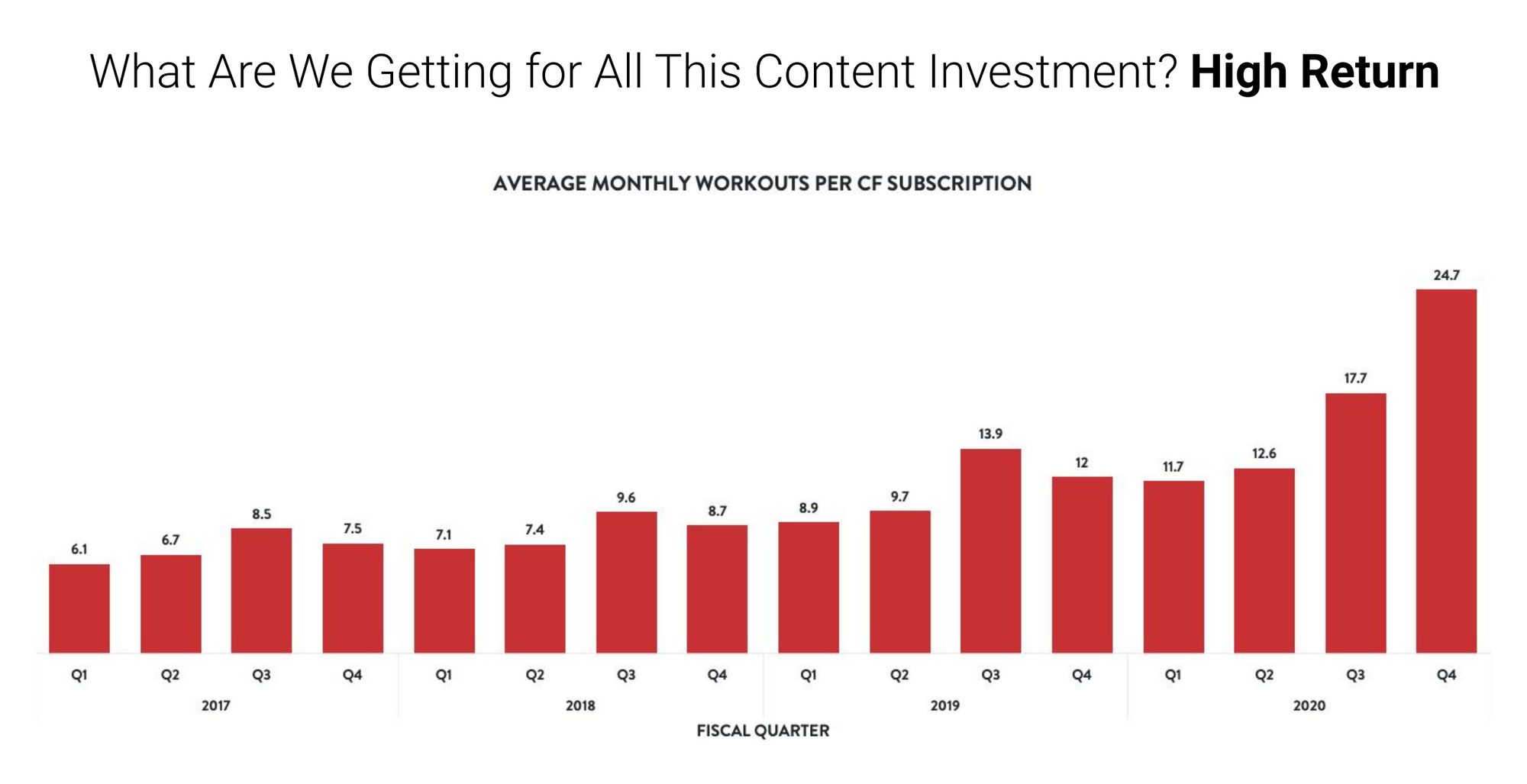

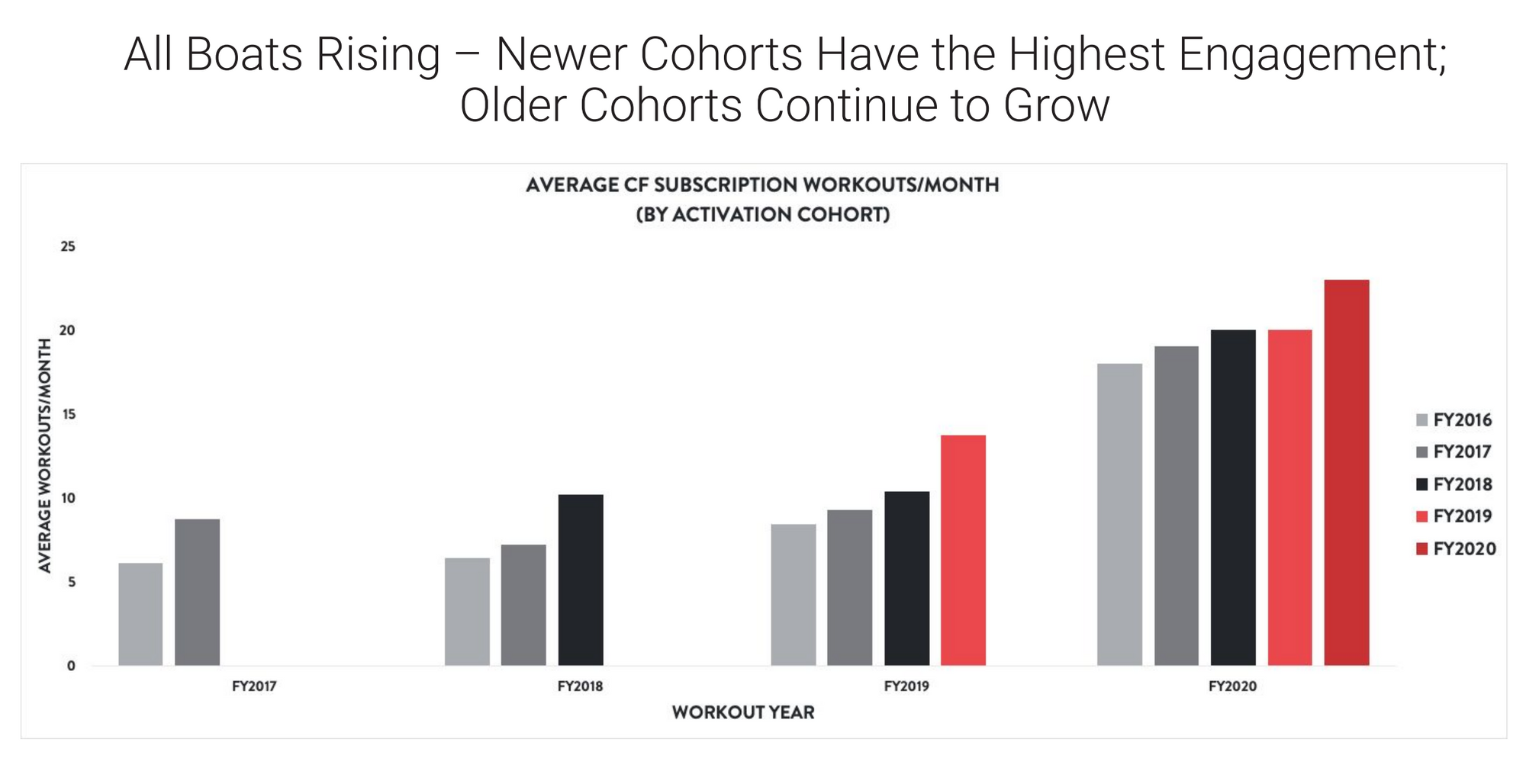

Throughout the pandemic and the consequent lockdowns, Peloton signed up a lot of new subscribers and all Peloton owners used their bikes and joined classes with regularity.

This positive trend fuelled significant strategic optimism within the group, inspiring them to dream even bigger and set ever more audacious future targets.

But as the lockdowns eased, even the most dedicated Peloton supporters started to venture outside for a run, a walk or alternative exercise time in a physical gym.

Peak lockdown numbers were never going to be sustained, but nowhere in their strategy documentation is there any recognition of this. It may well be that leadership simply expected historical trends to carry on into the future without really questioning this assumption.

It doesn’t appear that the Peloton leadership did any kind of scenario planning to envision what response they might have to falling consumer demand at the end of the pandemic, or how they would respond to to increasing amounts of competition in the connected fitness market from companies like Lululemon.

The ‘moat’ that they assumed they had in the marketplace, turned out to be a lot more porous that what they had estimated.

The Customer Treadmill

Since the easing of lockdown restrictions, Peloton have struggled to contain their increasing churn rate. Subscribers are not renewing like they used to and the cost of acquiring new subscribers is increasing. Now that they are forced to discount the price of their treadmills and stationary bikes to attract new customers, the upselling and cross-selling opportunities are far less lucrative than what they once were.

Throw all of these less than favourable metrics into a pot and your have a subscription business on the back foot.

No doubt their overall customer lifetime value (CLV) amount is not looking so rosy anymore either, which is forcing leadership into a reactionary position to try and find short-term solutions to the carnage.

The reality is that an online fitness subscription business is never going to be as big and successful as a music / movie / gaming / books business. The number of fitness fanatics in the world that are going to be loyal and dedicated to your offering under reduced pandemic conditions and beautiful summer days is limited.

The reality is that exercising is not like watching Game of Thrones – it’s a pain in the arse.

There are obviously people that love feeling ‘the burn’ as often as they can, but for the vast majority of humankind, they would rather smash a muffin in their mouths and take the dog for a walk around the park than have somebody screaming at them for 45 minutes telling them to ‘kick some ass’.

The total addressable market is limited…and fickle, and have a lot of other options to choose from.

In many ways, strategically at least – there just isn’t any recognition of possible threats or weaknesses in the Peloton SWOT analysis.

By ignoring the ‘shadow side’ of their business they created a dangerous blindspot that has had a dramatically negative effect on their long-term prospects. They drank their own sickly-sweet Kool Aid with reckless abandon…and it made them fat.

What Can be Learnt From This?

On the positive side, Peloton have creatively-built a powerful brand, and if they weren’t a listed company and hadn’t tried to convince everyone that they are disrupting the fitness market – this would still be a very nice company to be a part of / own / do business with.

They do have a lot of subscribers who are paying $12.99 a month to get their unique content. They do still sell quite a few treadmills and exercise bikes and generate lots of revenue, but all of this is just not good enough considering how highly-geared they are.

The big lesson here is one of cognitive bias and completely ignoring the signals of change occurring outside of the business.

The Peloton strategy is not realistic.

The numbers don’t make logical sense, the business model is too closed, the market far less lucrative than what they convinced themselves it to be.

They ignored the risks and didn’t plan for any possible downside. Perhaps this is yet another case of the dangers of the over-optimistic mental model that many technology startups have, coming into play yet again.

If all you are is positive about the future, it’s inevitable that at some point a flock of blacks swans is going to fly over you and shit on your head.

As their luck turned and things didn’t go their way, leadership appeared to be taken by complete surprise by each one of them.

It’s almost as if they never thought it in anyway possible that one of their treadmills might cause a tragic accident, or that maybe their initial popularity during lockdown might not be sustainable after lockdown, or that they might struggle to grow the business from such an elevated market position.

From an outsider’s perspective, the business doesn’t demonstrate any kind of strategic wisdom; there is no balanced view, there doesn’t seem to be anyone in leadership who is bold enough to tell the truth when they collectively look in the mirror.

A good strategy is one that is informed by what’s going on in the contextual environment; it’s one that is balanced, realistic and aware of blindspots and unimaginable events that may happen in the future that could affect the business.

A good strategy then is holistic and as honest and scientific as possible. Alternatively, lying to yourself and believing in your own lies is like drinking weak poison mixed with Coca Cola; it might taste nice for a couple of sips, but in the end you’re just going to make yourself very sick.

The case study was first published here.

Photo by Intenza Fitness on Unsplash.