A historical and biological perspective of how organizations can adapt to scarce resources and fierce competition

COVID-19 has hijacked our cells, our families, our work, and our freedom of movement, rippling economic devastation across the world. An unparalleled recession is here, and its effects could remain for years to come. The first phase of any recession is shock. The second phase is starvation: of resources—primarily financial—but also of opportunity.

For the last two months, businesses have been grappling with the question, “How long can we starve?”

How long can we keep our teams intact? How long can we stave off deep cuts? How long can we go before we have to cut long-term investment for short-term survival? How long can we limp by before things return to “normal?” These questions will undoubtedly follow us for many months to come.

Some small birds and mammals can literally only go a day without food. Human beings, we can last up to three weeks. Gandhi famously survived 21 days of voluntary starvation. Some reptiles can survive up to two years without food. However, the record holder in the animal kingdom, the Usain Bolt of deprivation if you will, is the European eel, which survived 1549 days without food. For those math-disinclined, that’s over four years without a single morsel to eat.

Animal, vegetable, or corporation–your survival strategies for starvation are relatively the same.

First, you can simply drop mass. Cut weight. Cut obligations. The question you face is how much you can tolerate without irrevocably harming yourself. A King Penguin can lose half of its body mass with impunity. So can man’s best friend. Of course, the speed of which you lose this mass is also critical. The King Penguin requires up to 70 days to shed its weight. Small migrating birds can drop 30% of their mass in mere hours. Best of all though, the aptly named Immortal Jellyfish can shed nearly all of its cells and return to a pubescent state, starting life all over again. Many of us are facing decisions right now about cuts: how far and how fast. Many, though, will either make the mistake of cutting their legs out from underneath them, or cutting too slowly.

Second, you can temporarily borrow what you need from existing reserves within your own body. In a pinch, humans can produce glucose from our pancreas to restore our blood glucose levels, giving us enough energy to push forward. We can also borrow energy from our lipids, replace lost organ mass with water, and even reach deep into our bones for fuel. Many of us are horse-trading resources internally, literally robbing (or firing) Peter to pay Paula. These tactics might buy us the precious few days we need between obligations, but there is a limit to how much we can draw from ourselves.

Third, you can scale back your efforts, decreasing your metabolic rate and your need for resources. Roaches, if starved, simply stop moving. Other animals, ones evolutionarily designed for the process, hibernate. But this is a risky strategy. A roach in dead-stop might just be a left-turn away from finding food and never know it; while hibernating bats make easy prey for snakes. In contrast, birds tend to actually increase their rate of movement when they’re starving, hoping to cover more ground in pursuit of a meal.

Many, many of us are cutting teams, efforts, and initiatives that in the harsh light of a pandemic and ensuing recession appear non-essential. These are hard decisions, especially when the future is impossible to predict and confounding to even forecast. Yet, stopping or even slowing innovation assumes two hypotheses: one, that the world will return largely to normal and two, that others aren’t using this time to find a way to disrupt us. In Alaska, it’s (sadly once again) legal to shoot a hibernating bear—and in a bear market, disruptors pick off easy prey.

Most of us will face cuts. Most of us will horse-trade for internal resources. Most of us will scale back the size of our ambitions. But none of us can afford to stop moving entirely. There is no “normal” in which to return. There is no great pause, no universal reset among our competition or our cultures. Instead, there is chaos, there is uncertainty, and there is a growing clash for limited resources.

There’s some evidence that seabirds not only ramp up their efforts when starving, but in fact, their search pattern becomes ever more focused and strategic—especially if they are rearing young. Yes, even birds are focused on ROI. Particularly when thinking about the future.

As we navigate this moment between the shock of a global pandemic and the reality of a global recession, all of us need to be prepared to become seabirds. We cannot starve ourselves into stasis, nor can we explore with abandon.

An exhaustive study of three former recessions found that only 9% of businesses truly emerged stronger after economic collapse. Detailed in HBR, the authors (including the Dean of Harvard Business school) assessed strategy and odds this way:

These postrecession winners aren’t the usual suspects. Firms that cut costs faster and deeper than rivals don’t necessarily flourish. They have the lowest probability—21%—of pulling ahead of the competition when times get better, according to our study. Businesses that boldly invest more than their rivals during a recession don’t always fare well either. They enjoy only a 26% chance of becoming leaders after a downturn. And companies that were growth leaders coming into a recession often can’t retain their momentum; about 85% are toppled during bad times. Just who are the postrecession winners? What strategies do they deploy? Can other corporations emulate them? According to our research, companies that master the delicate balance between cutting costs to survive today and investing to grow tomorrow do well after a recession.

We have to continue to search for resources, especially those critical to our long-term survival, with increasing dispassion and strategy in a downturn. But how? And how, efficiently?

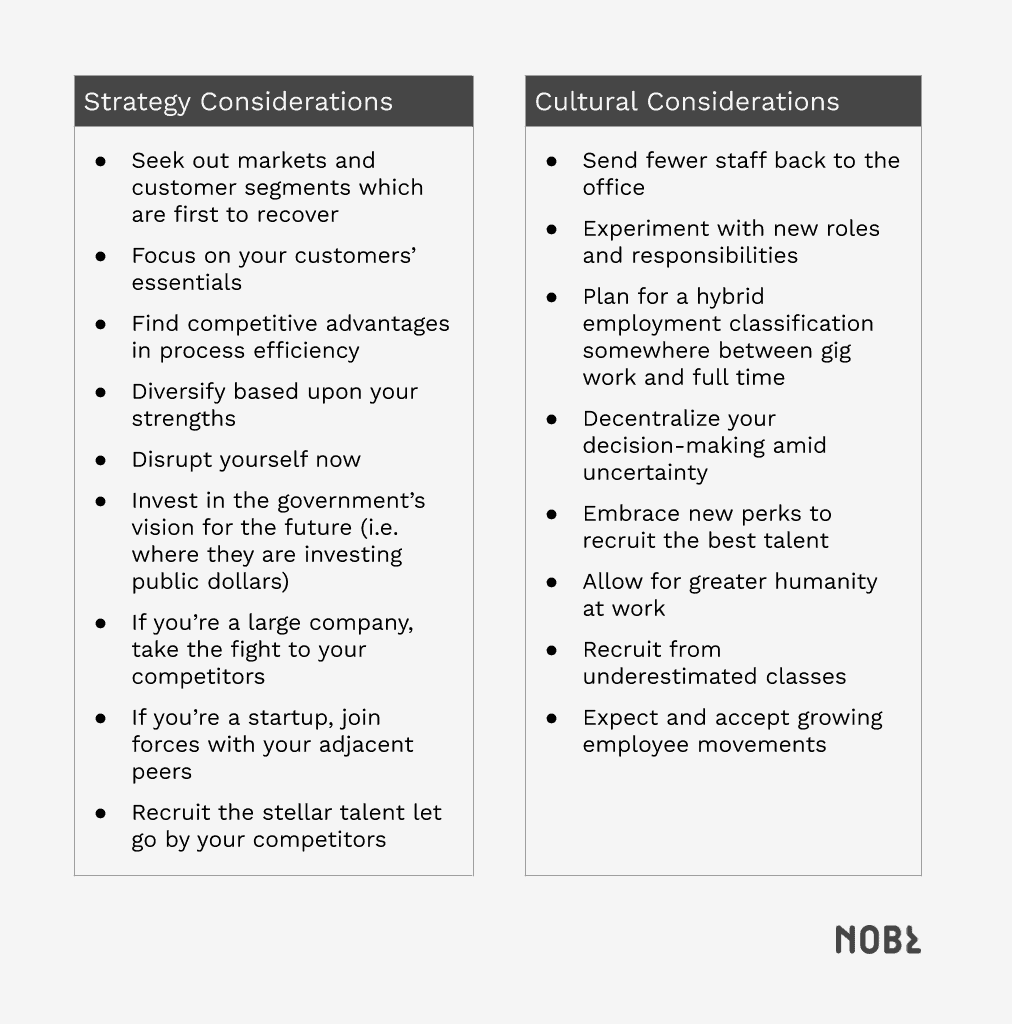

THE STRATEGIC RESPONSE TO RECESSION

- Seek out markets and customer segments which are first to recover. Due to their efforts in containing the virus, organizations may take a second look at Australia, New Zealand, and yes, even China as increasingly attractive markets. After 2008, LEGO saw profit growth of more than 60% by focusing on Asian and European markets, which were less affected by the housing market collapse than the US. Additionally, while Prius continued to target middle-class shoppers, Tesla began in the early 2000’s by targeting wealthy individuals (with an electric roadster) who were harmed the least by the compounding of the dot-com bubble and 9/11. Ask yourself: who, if anyone in your organization, is poring over your customer segments and geographies to forecast who and where might be first to recover?

- Focus on your customers’ essentials. After the 2001 recession, Target began losing ground to Walmart’s guaranteed low prices. In response, Target expanded their stores to focus on food and related groceries, which were absolute necessities. Target also began partnership programs with Amazon and high-end clothing designers to deliver cheap, yet unique fashion products for a population who wanted to express themselves with the fewest possible dollars. Ask yourself: who, if anyone in your organization, is brainstorming new products that will meet essential customer needs, both known and emerging?

- Find competitive advantages in process efficiency. During the Great Depression, GM leapfrogged Ford Motors by standardizing their parts (including engines) across every product line. This not only made their cars cheaper, but it also made supplies more responsive and flexible to demand. While it’s easier to simply cut payroll costs to reduce your burn rate, it’s far more strategic and beneficial long-term to focus on process efficiencies. Ask yourself: who, if anyone in your organization, is deeply investigating your processes and questioning old dogmas to find both savings and new opportunities?

- Diversify based upon your strengths. C.F. Martin & Company, famous for their Martin guitars, exists today because during the Great Depression, they used their woodworking prowess to produce everything from violin parts to wooden jewelry while also experimenting with a three-day work week. Ask yourself: who, if anyone in your organization, is exploring adjacent categories that might be ripe for competition based on your core competencies?

- Disrupt yourself now. Understanding that digital technologies would undoubtedly disrupt their business model, Fujifilm, in contrast to Kodak, initiated a major corporate restructuring program and dubbed it their “second foundingm” demanding that employees challenge long-lived sacred cows. Moreover, in the middle of the 2008 recession, Domino’s Pizza ran an ad campaign acknowledging their lack of quality and promised to spend millions in new development. Their stock has increased by a factor of 33 since then. Additionally, during the dot-com crash, Netflix came hat-in-hand to Blockbuster and asked to be bailed out for $50 million dollars. Blockbuster nearly laughed them out of the room. Today, Blockbuster is dead, and Netflix has a market cap of $187 billion dollars. If you know you’re behind the curve or on the bubble for disruption, who, if anyone, is strongly arguing for this to be a moment of reinvention?

- Invest in the government’s vision for the future (i.e. where they are investing public dollars). Chrysler benefited from the Great Depression by betting on the New Deal’s promise of interstate highways. They built cars with bigger engines and greater range, which positioned them competitively in the new era. As governments develop longer-term stimulus packages, who will you task to keep an eye on where that spending is going?

- If you’re a large company, take the fight to your competitors. During the 1970’s recession, Burger King’s owner, Pillsbury, was wary of opening new stores during a downturn. In response, McDonald’s doubled its stores in the U.S., which has remained a competitive advantage ever since. As resources dwindle, the worst strategic sin of a recession is to ignore what your competitors are doing. Are you, even at the board level, increasing your competitive sensing, and discussing if you can swing big where competitors choose to bunt?

- If you’re a startup, join forces with your adjacent peers. During the panic of 1837, candle maker William Procter and soap maker James Gamble joined forces to start a small household-goods business in Cincinnati. P&G survived years of recession and went on to win lucrative contracts to supply necessities to the Union Army during the Civil War. Additionally, the IBM we know today is the amalgamation of three startups: the Tabulating Machine Company, the International Time Recording Company and the Computing Scale Corporation. These three companies merged during the Panic of 1910-1911 as the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, which changed its name to IBM several years later. As a team, are you forecasting out possible futures and identifying what adjacencies may become critical competitive advantages?

- Recruit the stellar talent let go by your competitors. Now is the moment to strategically source. Thomas Edison, during the Long Depression that began with the Panic of 1873, sought out inventors and engineers who had suddenly become available due to uncertainty and panic. Are your hiring managers keeping a keen eye on your best competitors and their best talent?

THE CULTURAL RESPONSE TO RECESSION

In a recession, we readily acknowledge that our strategies must shift. Fewer resources require greater competitiveness—that’s obvious. But less intuitively, our workplaces and workforce must change as well. And in fact, economic downturns have consistently altered the way we work. We must be prepared not just to rewrite our strategies, but to question how we work together. After all, an organization’s culture should be designed to align how to win in the market with how to work together.

- Send fewer staff back to the office. All of the old fears of going remote are being vanquished during this period of forced quarantine. Employees are proving themselves accountable and engaged, even amid a global pandemic. Many leaders we’re speaking with plan to keep up to 40% of their workforce remote in an effort to cut overhead costs during and after the recession. Now’s the time to determine what jobs must be co-located, and what jobs can remain remote. Of course, both populations will require special support.

- Experiment with new roles and responsibilities. Before the railroads connected the 48 contiguous states in the late 1800’s, there was no such thing as a “middle manager.” With the ability to source and sell far across state lines, not only were “Mom and Pop” outfits decimated, but the need for a new role in the organization emerged. COVID will likely trigger the same need for emergence. Expect additional health and safety roles in physical offices, for increased investment in developing resilience in supply chains and distribution channels, beefed up crisis communication resources, possibly psychotherapists to help employees cope with loss, grief, apathy, and detachment, culture coaches to keep a majority-remote workforce engaged, and so much more. Start experimenting now with these roles; they may well prove to be a competitive advantage.

- Plan for a hybrid employment classification somewhere between gig work and full time. The 2008 recession led to an explosion of gig jobs as workers were hustling to find ways to make ends meet. This recession is testing the American healthcare sector, and those gig workers are leading protests and strikes demanding a new distinction of employment that would guarantee some level of security, for both health and finances. Expect fierce American individualism to reckon with overall security in the months and years to come. Begin assessing the costs and consequences of a new employment classification.

- Decentralize your decision-making amid uncertainty. In a 2017 study, researchers found that organizations that could distribute decision-making more locally (in this case, to individual manufacturing plants) ultimately made better decisions and emerged more successfully because they were empowering those with the best information with the power to act. This may very well be the time to flatten your org chart and distribute greater authority.

- Embrace new perks to recruit the best talent. Health insurance provided by your employer was invented as a perk during WWII in the US, when the government froze wage increases. Casual dress was a perk invented in the downturn of the 1990’s to boost morale without increasing salaries. It actually broadened an emerging trend called “Aloha Fridays.” (Fun fact: Dockers capitalized on this trend by sending HR managers a copy-paste casual dress code policy and offering a 1-800 hotline to help resolve questions and infractions.) Companies will be asked to offer top talent greater benefits with fewer resources, so expect a new trend in employee perks. Our top bet? Four-day work weeks will become THE hot new recruiting tool.

- Allow for greater humanity at work. Right now, we’re OK with your two-year old crawling all over you during a status call—why should that change? The expectation that we are family-less drones at work should be challenged, even when we can return to business as somewhat usual. In many categories, our families make us more empathetic to our customers and their daily struggles. Why would we want to firewall that insight from our corporations?

- Recruit from underestimated classes. In the US, WWII finally brought women into the workforce in large numbers and effectively doubled America’s productivity. In our current downturn, companies should rethink their talent profiles as we rebuild the global economy. Those unnecessarily left behind due to age, abled-ness, or past offensives should be recruited back into the workforce. Of course, this should be done on top of more traditional diversity and inclusion efforts.

- Expect and accept growing employee movements. In 2019, we saw employee activism spike: Google employees walked out to combat sexual harassment, Amazon employees who held shares rallied together to force a climate change response, and now, during COVID, we’re seeing front-line employees strike for safer working conditions. This week, an Amazon VP quit in solidarity with front-line staff. There’s even a digital platform called Frank to help employees rally for change. The truth is, in a world where governments are less than responsive to our needs, employees will demand social and environmental justice in their places of work. Simply ignoring or tamping down these movements will increasingly implode in our faces, so develop a strategy now to listen and respond to employee demands.

IN CONCLUSION

For businesses, like animals in the wild, a change in the environment should inspire us to reflect and potentially reorient. The universal and dramatic changes caused by COVID-19 call for an equally dramatic rethink of our organizations. Legions of articles and case studies will be written a decade after this catastrophe declaring the business leaders from this era. Guaranteed, none of those articles nor the market will lionize the companies who did nothing in response. You must act. Deciding how far, how wide, how fast, how incremental, and how disruptive will be a test of your leadership. The one thing we know for certain—the one truth that we know will emerge—is that strategy and culture are intrinsic and interdependent in moments like this. How to win together (AKA strategy) and how to work together (AKA culture) have never been more interconnected or interdependent.

This article was first published here.

Photo by John Cameron on Unsplash.

5.0

5.0