For IT to function better, the business side of the company has to get more

involved.

How many times have you heard a variation of “Business and IT need to work better together”? That piece of advice contains one of the most important shifts companies can make to establish a technology capability that enables them to compete effectively in the digital age.

Some companies have made changes, such as giving product managers new product-owner roles. But without sufficient training or changes to team dynamics, those shifts often remain superficial and don’t improve team performance. Too many companies are still too quick to point the finger at IT for every technical woe, from development delays to cost overruns. Casting IT as scapegoat can be a hard habit to change.

That’s not to say there isn’t plenty of room for improvement on the IT side of the house. Efforts to modernize technology—from addressing tech debt to migrating to the cloud to building up tech talent—all require significant improvements in how IT works and where it sets its priorities. But in a time when the technology capability is a source of competitive advantage, why doesn’t that happen more often?

There are many reasons, but the solution comes down to something that’s deceptively simple: if IT is to become a real driver of value, both business and IT must overcome bad habits and make a real commitment to being partners. That implies adoption on both sides of processes, mindsets, and capabilities that reinforce the mechanisms that nurture habits that can improve technology performance.

The Trouble With Go-Betweens: Accountability

Because technology can seem confusing, opaque, or intimidating, those on the business side prefer to leave it to the ITexperts. To bridge the disconnect, companies have turned to dedicated “go-between” roles as part of a well-meaning effort to make IT more responsive and customer oriented. Individuals variously designated as “translators,” “demand IT,” “business requirement managers,” or “IT process managers” take business requests and turn them into clear requirements with instructions for workers on the IT side, many of whom work offshore.

Unfortunately, the effect of these roles is often reduced accountability on both sides of the divide. On the business side, managers are content to define requirements without understanding how technology can best deliver on them and to, in effect, wash their hands of the whole IT development process. On the IT side, translators often simply accept requests from the business side without understanding the core issue, so they don’t think through the whole range of possible technology solutions. Even when the go-betweens speak for business needs and even report to or sit on the business side of the organization, they are seldom evaluated in terms of their P&L results. Meanwhile, the addition of an intermediary layer between business and IT slows time to market, which impedes digital efforts to accelerate the pace of business practices.

The Four Levels of Business–IT Integration

The ultimate goal is to connect the top-level business strategy defined at the boaFrd level to technical implementation in IT. That means negotiating four levels, and business needs to be knowledgeable about, and involved in, all of them:

- top management/board level

- business process implementation

- IT governance

- technology platform

Each of these four levels can accelerate or slow down the development of new internal or external functionalities for the customer. But for the entire model to work effectively, it is important that the levels are aligned in their degree of maturity; being strong in one area and weak in another doesn’t work well.

Level 1: Top Management/Board Level

The measure of something’s importance to an organization is the seriousness with which it is addressed at the top levels of leadership. That means both the C-suite and the board should have technology as a top priority on their agendas. Without that, the business will have a difficult time making the decisions and investments needed to modernize and scale technology. There are two actions top management can take to demonstrate their commitment to IT:-

Prioritize IT at the C-suite level. Business attitudes and behaviors toward IT won’t shift unless business leaders—the CEO and CFO in particular—get personally involved. This personal commitment is

necessary because, even when there is a high-level acknowledgement that digital and technology are important to

the board, the actual time and energy spent on them often don’t reflect a real commitment on the business side.

At one large consumer company, for example, an effort to modernize enterprise resource planning (ERP) failed when it was treated as purely an IT project. That’s because many of the issues that affected the ERP system, such as the warehouse structure, fell outside the scope of the IT department. The modernization effort was therefore complex and costly to maintain. To redress these issues, leadership made ERP the subject of board-level discussions and ensured that the business and IT sides worked on it together. This created shared accountability and incentives. Top management focused on changes to both the IT systems and the business architecture, such as how the warehouses are set up.

-

Understand how IT decisions affect the business. In quite a few companies, the lack of business involvement with technology stems from discomfort in the board or C-suite with IT topics. The result is that technology is deprioritized and seldom discussed.

Decision makers on the business side need a good basic understanding of technology. They don’t need to know how to write code, but they do need to understand what different technologies do. When one CEO decided to give IT a more prominent role in his organization, he sent his whole top-management team to technology training courses. His rationale was that learning about how cloud works and how systems depend on each other would enable them to make more educated decisions for the business on IT matters. This training was also widely reported in the company, sending a strong signal to the entire organization that technology savviness was important. (Read more about how leaders can model change.)Take, for example, the latency behavior of integrations in an enterprise service bus (ESB). This is a highly technical issue, but poor execution can cause delays that affect a website’s performance, which makes it a business issue as well. In this case, business leaders need to be able to understand the latency issues around ESB integration and work with IT to reduce them.

This same level of understanding is also required by the IT side. IT has to be aware of business realities when developing IT solutions. A handheld device developed in a warm office, for example, will likely fail if its primary business use case is in cold weather.

Level 2: Business Process Implementation

When the board makes a tech-related decision, it is primarily up to the business to translate it into a business process that can be implemented. That requires the business to work with IT to set KPIs, put together the right teams, and develop strategic road maps. Business stakeholders need to build specific capabilities and shift mindsets across the following dimensions:Empower your product managers. Empowered and knowledgeable product managers (or product owners) with the autonomy to direct their teams toward specific goals is one of the most important factors in a tech-forward organization. A good product manager combines both business and technology skills with the operational skills to effectively lead teams.

The lack of delegated decision rights is one of the major issues that can defang an effective agile operating model. In many cases, the issue is that there is a “proxy” product manager within IT. While this person might be formally qualified as a product manager, he or she usually doesn’t have the mandate to really change the business side’s processes and approach.Make tech competency a career necessity. It’s often considered a bad career move when a business-side person moves to work on an IT initiative. One company handpicked people from the business side to lead a large-scale program that the CEO had acclaimed as a huge opportunity, only to find that the few people selected to help lead the program turned it down because it was in IT.

Business leaders need to flip the view of working with IT from career killer to career builder. One way to do that is to ensure that employee career planning includes a technology element—for example, through structured rotational and exchange programs in which business managers work with IT.

In the same vein, tech knowledge and experience should become a necessity for anyone wanting to move ahead, regardless of role. Incorporating technology modules into learning journeys, for example, can help ensure people on the business side continue to build up their technical knowledge. This can include, for example, helping business people to use low code/no code tools, harness emerging generative AI tools to help with specific tasks, assess vendors, and analyze data.

Classic role modeling is also important. When prominent business leaders drive IT initiatives, it signals to the company that IT is important. At a major retailer, for example, the former CFO of a country led a major IT transformation program. Similarly, a large data-governance and data-architecture initiative at a major CPG company was led by the CFO of one of its main divisions.

Co-lead instead of “partnering." Despite best efforts to get business and IT collaborating more effectively, companies still often end up with a culture clash where the two sides still see each other as adversaries. That can be fixed only through fundamental changes in incentives, processes, and operations.

In our experience, it can be helpful to treat business–IT collaboration like post merger management, which provides for a more systematic approach to tackling cultural and logistics disconnects that keep teams from working together. Aligning incentives for both the business and IT is often a good place to start. Similarly, a focus on culture building needs to be supported with incentives such as relevant business units contributing the budget and nominating a senior leader to act as the product owner for joint business–IT solutions.

Level 3: IT Governance

An effective operating model has a defined business process and the technology capability to deliver it. An operating model, however, is only as successful as its ability to incorporate the business side through effective governance practices. Following are a few proven steps:Translating IT decisions into joint business objectives. In most companies, IT has a budget cap based on the average industry spend, and that cap rarely moves. However, if tech initiatives are expressed in terms of a clear ROI, the CFO can more easily judge whether developing a new application is a better investment than, say, opening a new store.

One area where looking at IT through a financial lens can be particularly helpful is in managing tech debt (the cost of dealing with legacy issues when developing new tech products or services). CIOs estimate that tech debt amounts to 20 to 40 percent of the value of their entire technology estate before depreciation. Yet companies seldom know the cost of tech debt for a given initiative or factor it into the work they do. IT can help the business understand the cost of tech debt by pricing it into all IT projects.

Ideally, the cross-functional team has joint objectives and key results (OKRs) that reflect the business and the IT objectives of the respective area.

- Communicating in business terms. IT people need to understand what’s important to the business—value, ROI, cost, customer experience—and to be able to explain IT’s contribution in those terms. This should be an exercise not in dumbing down IT for the uninitiated but in clearly articulating the implications of technology for the business. That means not only describing the immediate benefits (such as higher conversion in a particular step of the checkout funnel) but also the full monetary value—in this case, the EBIT impact of the improved conversion rate.

Level 4: Technology Platform

When it comes down to actually developing technology products and services, companies need to navigate a lot of buzzwords (DevOps, DevSecOps, agile, CI/CD). In essence, these are processes that all encourage closer collaboration at the operational level to reduce waste and accelerate time to market. While it’s not realistic for the business to be involved at the coding level, understanding how supporting systems can impact development is critical to helping prioritize investments and resources, particularly in two areas:- Digital platform. When developing new functionality, IT teams often spend the first weeks or sometimes even months of a project deciding what tools to use and tapping other IT teams for additional functionalities they have developed. A “digital platform” can reduce that wasted time by providing teams with a more user-friendly, “batteries included” standard set of tools and processes to test and deploy new functionality. It also includes up-to-date documentation on how to get functionality and data from other teams through APIs. This accelerates the development of new systems and the reuse of existing functionality.

- Automating IT systems. Automation has made major strides in IT, but significant issues exist. Compiling the software and distributing it is often automated. But what about testing? Are architecture rules and regulations tested automatically as part of the deployment, or are they available only on paper or an intranet website? Business and IT should not view automation as a capability they apply only in certain places; it needs to be a core feature of how IT runs.

Going Forward: Ensuring Consistency Across Levels

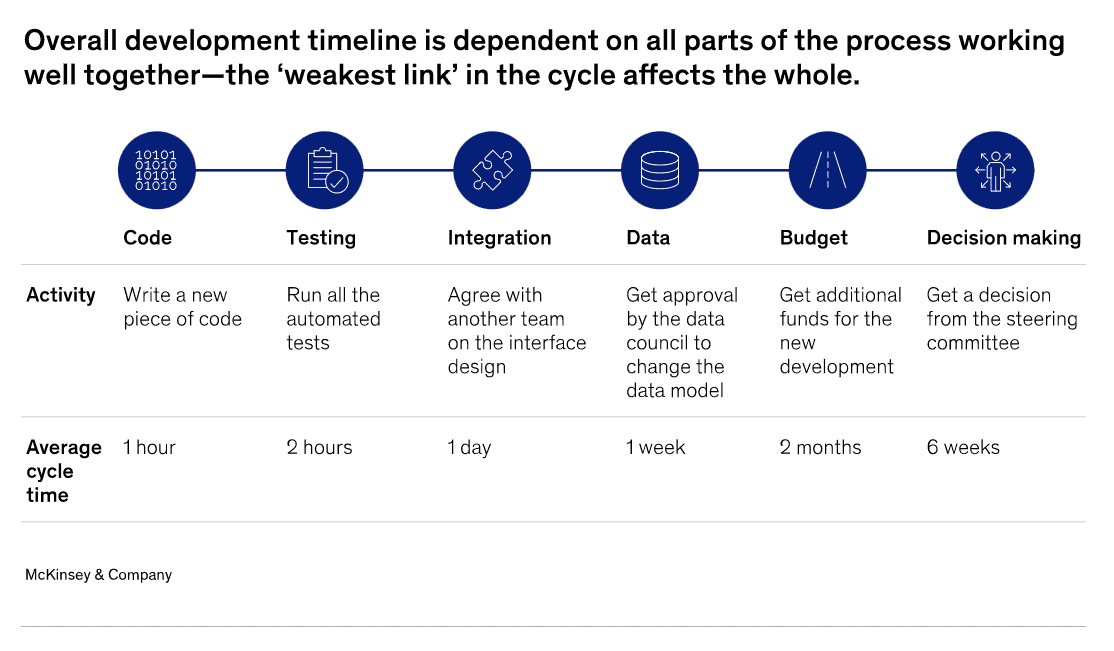

Effectively bridging the gap between business and IT requires alignment across the four levels outlined above. This interdependency is why it’s much more important that all the elements reach similar levels of maturity than to have a few that perform well and a few that perform poorly. This is the classic “weakest link” principle, where weakness in one area is sufficient to undo the whole (exhibit).

A business might have a fantastic agile program where business and IT work together, but if they don’t address technical debt for the products they’re developing, for example, that working relationship is not well served.

Companies should figure out their basic levels of performance across these various elements to identify performance inconsistencies. This analysis needs to highlight breakdowns in the business–IT relationship and areas where that relationship should focus its energies. To help companies develop a view of their business–IT working effectiveness, we have developed a quick diagnostic with questions that correspond to each level.

1. Top management/board

Board-level importance

How much time does IT get in your board meetings?

- Level 1: The board focuses on IT only when there is an emergency issue, such as a cyber breach.

- Level 2: Technology is rarely on the board’s agenda and is typically covered in a short slot.

- Level 3: Technology is a standing item on the board agenda and is discussed at each meeting, and/or the CIO is a member of the board.

Technical knowledge

How comfortable are your C-suite and board with technology topics?

- Level 1: A little. Only one or two people outside of the CIO or CTO are deep in technology.

- Level 2: Most of the C-suite and board can talk about technology and its implications for the business and have enough knowledge to make good decisions.

- Level 3: Very. Most board members and the C-suite actively go to see other companies and meet technology leaders to understand current and future trends. They can ask good, probing questions of the CIO or CTO that help lead to better outcomes.

2. Business Process Implementation

Career paths

How often do employees move roles between business and IT along their career path?

- Level 1: It rarely happens, and if it does, it’s usually a one-way move.

- Level 2: People change frequently between business and IT along their career path.

- Level 3: There is a career-path model where career advancement is tied to methodical role progression through both IT and the business.

Decision rights

How quickly can you make decisions that have a major impact on digital products?

- Level 1: Decisions remain hierarchical, requiring long review and approval processes.

- Level 2: Decisions are made jointly by a steering committee and a product owner reporting into IT.

- Level 3: Product teams are fully empowered to make decisions on the spot, including the redesign of business processes and changes impacting the outcome of a process.

Team culture

How well integrated are business and IT teams and governance?

- Level 1: Business and IT targets are set independently from each other and have different performance criteria (for example, IT’s are for cost and the business’s are for ROI).

- Level 2: Business and IT hold joint forums and set joint targets on a high level but are not synched at the team level.

- Level 3: Teams are fully integrated, with shared KPIs and performance goals, and there is no distinction between business and IT.

3. IT Governance

Steering and incentives

How are product teams managed?

- Level 1: Teams are measured by input factors, such as time in the office or amount of code released.

- Level 2: Teams are measured by outputs such as productivity that are similar across teams and are set by a central function.

- Level 3: Teams act like mini start-ups, defining their own clear OKRs, KPIs, and incentives. They are measured by reaching their objectives.

Investment decisions

What are the key decision criteria for starting a new IT project?

- Level 1: None, not formalized, no business case, or not tracked

- Level 2: Separate business case and IT objectives

- Level 3: OKRs that are linked to P&L and monetary targets that are tracked

4. Technology Platform

Release frequency

How often do you get new functionalities to end customers?

- Level 1: Typically in quarterly releases

- Level 2: Monthly, based on agile methodologies that are tailored to a large corporate environment, such as a scaled agile framework (SAFe)

- Level 3: Continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD), with daily releases and true ownership within the team

Automation support

How automated is the process for a developer to start a new project for a new application?

- Level 1: A loose set of good practices is centrally collected and shared with the community of developers.

- Level 2: The standards are defined, but getting access to the tools required takes a developer team several days.

- Level 3: The standards are codified as part of a digital platform that developer teams can use as a self-service.

The article was first published here.

Photo by James Harrison on Unsplash.

5.0

5.0