A kindly uncle wants to help his niece out, who owns a small bakery. He is the director of a supermarket chain and puts a call into the head of procurement suggesting the supermarket take his niece on as a supplier. He mentions that he would personally appreciate it if the procurement head did everything he could to help.

A joint venture partnership is being considered by the board, and two companies are potential options. One of the directors is a substantial shareholder of one of the two companies being considered, with the shares held by a proxy. He intends to use his position on the board to ensure that his preferred company is selected for the partnership, even though the other is a better option.

A senior manager is reviewing several proposals for a major project. One of the bidders calls him and says they would like to fly him to Australia for a two-week fact-finding tour so they can show him similar projects they have completed. His wife will be welcome to come too at their expense. In exchange, it is naturally expected that the manager will return the favour and do what he can to ensure the bidder secures the contract.

Although very different, these scenarios all have something in common: they are examples of a conflict of interest. In some cases, it is the person themselves who will benefit, while in others it is a family member, but in each case, the director is breaking the law and can be subject to fines and even jail sentences.

How Do We Define a Conflict of Interest and Why Does it Matter?

A conflict of interest is a situation of divided loyalty where a person or entity’s own interests (or the interests of a related party) conflict with the interests of another party they are serving, normally the company they work for. This may compromise their objectivity, impartiality and integrity and so result in them failing to act in the best interests of the party which has placed them in a position of trust. A related party in a business setting is ‘a director, major shareholder or person connected with such director or major shareholder’ (Bursa, Para. 1.01 of MMLR).

Conflicts of interest can result in long-term substantial damage to a company and its people, including:

- Mis-awarding of contracts

- Leakage of business-critical information

- Directing company strategy away from or into areas which benefit an external party at the expense of the company

- Appointing people unsuitable for the role

- Withholding or covering up crucial information the company needs to perform well

- Interfering in investigations and disciplinary procedures, including serious misconduct such as fraud, bullying or harassment

Three types of conflict are generally recognised: actual, potential and perceived.

- Actual: A real conflict exists which must be disclosed and managed. For example, the close relative of a key decision-maker is bidding for a company contract.

- Potential: A situation is developing which could lead to conflicts as it progresses. For example, a close relative of a key decision-maker may bid for a project that is being prepared for tendering.

- Perceived: There may not be a real conflict but it could be perceived to exist. For example, the CEO of a company bidding for a company contract has the same family name as a key decision maker, but in fact they do not know each other and are not related.

Legislation and Regulations

In Malaysia, conflicts of interest are covered by both legislation and regulations. These include:

- Companies Act 2016 sections 218 to 222; 228

- Bursa Main Market Listing Requirements (MMLRs), updated in 2023

- The Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance (MCCG 2021), especially sections 3.1, G5.6 and 11.2

- Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2009 section 16 (a)

The Companies Act and the MMLRs include not only directors but senior management. The new MMLR requirements are much more specific than previously, stating that directors, key senior management, including the CEO, CFO, and legal representatives must declare conflicts as soon as practicable. Reports must be made to the Audit Committee covering:

The nature and extent of any conflict of interest or potential conflict of interest, including interest in any competing business that such person has with the listed issuer or its subsidiaries. (Changes from the previous MMLRs are underlined in the original text).

The Audit Committee is then responsible for reviewing, approving, instructing on, overseeing and reporting on such conflicts to ensure they are managed correctly.

There is also a close relationship between some forms of corruption and conflicts of interest. The MACC Act section 16 (a) states that ‘gratification’ – anything of value – which is demanded or received with the intention of influencing behaviour is considered as a corrupt act. The form of gratification may be a tangible/material item (something you can hold or touch), such as an expensive watch, electronic device or cash, but it may be an intangible / non-material benefit (something you can’t hold or touch but still has value) such as an overseas trip, use of a car, or payment of school fees. Either way, if gratification is used to influence decision-making behaviour, this creates a conflict of interest whereby the person puts their own well-being above the interests of the organisation which has placed them in a position of trust.

On occasions, people may have a conflict without realising it. They see it as simply trying to help a family member, or a cultural norm, or perk of the job which ‘everyone does’, such as receiving an expensive festive hamper or being dined lavishly by a vendor. In cultures with strong, people may consider it their duty to use their influence to ensure a friend or relative secures a lucrative contract or good position in the company. This area can be tricky to navigate, especially where a company is both listed and substantially family-owned, and there is an expectation of jobs for family members, but not all family members may be competent. Such situations require wisdom, good processes, and strength of mind to ensure that the right people are placed in the right positions.

Conflict Management

We can see now that awareness and understanding of what constitutes a conflict of interest and how these situations should be handled are crucial to ensuring they are dealt with correctly. This not only safeguards the company but also the long-term reputation of the people involved.

How Should Conflicts be Managed?

- Corporate Training. Training is essential. Examples and case studies should be included to ensure directors and key personnel understand what a conflict is, the various forms it can take and how it should be handled in practice. Training on related party transactions should also be included since this field is closely connected to conflicts of interest.

- Transparency. A culture of transparency should be fostered, whereby people are positively encouraged to make disclosures. This needs to be supported by simple and easily understandable processes, together with specific training for the people who may receive a declaration from those who report to them. Disclosing a conflict can be a nerve-wracking experience, and it may also be greeted with hostility if the declaration creates stress for the management team once it is made, and this needs to be dealt with proactively.

- Conflict of Interest Declaration. The requirement to make a declaration as soon as the conflict is identified should be included in the employment contract. There should also be regular declarations by people in key positions (annually or once every two or three years, depending on their role) whereby people must state explicitly that they either have had no conflicts or have already declared them. These instruments can be useful if disciplinary and/or legal proceedings come into play at a later stage.

- Safe Space. Provide access to confidential and supportive help so a person who is unsure if they have a conflict can discuss the matter in a safe environment to see if a declaration is necessary. Having a helpline that connects to a team or individual with the necessary expertise, usually in the HR department, that is widely communicated throughout the organisation can help immensely

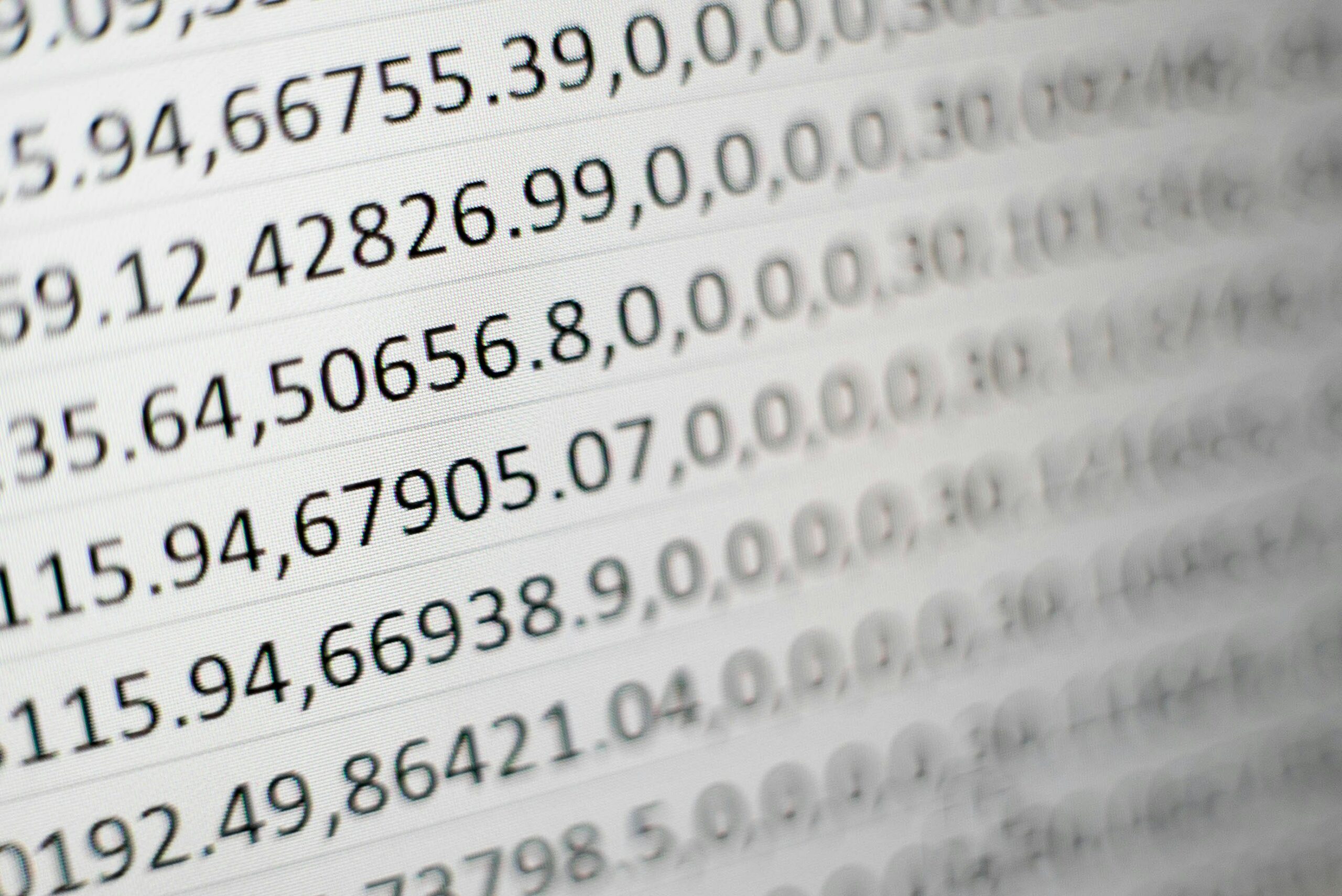

- Artificial Intelligence. If a conflict of interest is proving lucrative, it is unlikely that people will make a declaration. Until recently, it has been very difficult to find a way to identify, for example, if a senior manager had shares in a vendor supplying the company. With the advent of artificial intelligence, however, there are now instruments available that can do a large-scale data processing exercise very rapidly and identify if there is a crossmatch between key company personnel and the owners/directors of companies in the supply chain. This is proving useful for the regulators and enforcement bodies to identify and intervene in actual conflict of interest situations.

Once a Conflict is Declared, How Should it be Handled?

- An element of containment is necessary. This may include a degree of exclusion or restricted involvement in certain meetings, access to information and participation in the decision-making process.

- Additional controls can be useful, such as the conflicted person signing a statement that they will not divulge information or assist the other party, with legal sanctions for non-compliance.

- In some cases, it may be necessary to transfer the person to a different role. Very exceptionally they may be required to resign, but this is the last resort when a strong conflict is present and cannot be managed in any other way. If a transfer or resignation is the only option, the person’s integrity for making the disclosure should be recognised and they should be well-supported through the process. If making a declaration is seen as hazardous, people will hold back even if they should declare, causing more problems for the company in the long run, so getting this right is crucial.

Key takeaways

- Chairmen, directors, and management should understand, recognise, and know how to manage conflicts of interest successfully. Conflict of interest training should be included in the upper management and board levels as the legal consequences of failing to disclose are severe.

- Companies need to have a straightforward way of disclosing and managing conflicts at all levels, with readily available support from people equipped to help.

- A culture of transparency and openness will help people disclose conflicts. The Chairman, directors, and upper management setting an example by disclosing conflicts at the outset encourages others to follow suit.

- New technology solutions are available to identify undeclared conflicts.

- With the right processes, training, and support, conflicts can be managed easily and well, creating a healthy environment for the organisation to thrive.

This article was written by Dr Mark Lovatt, a corporate governance expert based in Malaysia specialising in anti-corruption, ESG, and the use of advanced technology to strengthen compliance. Dr Lovatt is on the ICDM faculty and conducts training in governance and integrity, including conflicts of interest and related party transactions. He can be contacted via ICDM or mark.lovatt@trident-integrity.com.

Photo by Eric Prouzet on Unsplash.

5.0

5.0