Unless you’ve completely avoided social media, major newspapers, advice columns and, basically, talking to people at work, you’ve encountered increasing buzz about “quiet quitting,” a term being used to describe employees pulling back (or being perceived as doing so) from their organization, prior level of effort, etc.

The big questions are: Is it real? Is it new? And is it bad? Let’s tackle those one by one.

Is It Real?

Yes-ish. The “ish” — which my fellow Minnesotans will appreciate — is added because in reality what’s happening is neither “quiet” nor (necessarily) about “quitting.” It’s also not one uniform experience with a single root cause. Rather, the data patterns point to two primary employee experiences at play:

- Employees are energized… just not by what’s going on at work. The pandemic has caused a radical reprioritization for many in the workforce, who have decided there’s more to life than huffing up a corporate ladder.

- Employees are fatigued… largely by what’s going on at work, but not exclusively so. As a result of the Talent Uprising, many organizations are short-staffed, leaving remaining employees to cover more than one person’s job, but still on one person’s salary. They’re tired of saying the same thing on employee survey after employee survey and not feeling heard as leaders sit on their hands rather than taking decisive action.

From a data standpoint, it shows up subtly but clearly. Kincentric’s global engagement database comprises about 10 million survey responses. We measure three distinct behaviors that exemplify engagement: what employees SAY about working at the organization, how likely they are to STAY at the organization and how motivated they are to STRIVE on behalf of the organization. The Talent Uprising has caused a keen focus on the STAY element, but here we see indications in the STRIVE component.

Two engagement survey items measure STRIVE:

- This organization inspires me to do my best work every day

- This organization motivates me to contribute more than is normally required to complete my work

The pattern seen is that while many employees still seek to do great work, discretionary effort as measured in the second item is softening. You can imagine employees in the first scenario above saying, “Hey, I’ll do my job really well, but life is short, and I want to also spend time with family, pursue other interests and enjoy myself.” The second scenario could sound like, “I’ve been a trouper for years — going above and beyond and beyond and beyond. But I just don’t have more to give. Seriously, the organization has to fix this.”

Across our global database, in comparing 2019 to 2021, STRIVE stayed flat. As is part of a larger pattern, though, this stability is an illusion. “Best work every day” increased by one point (a statistically significant difference given the population size), and “contribute more than is required” declined by one point.

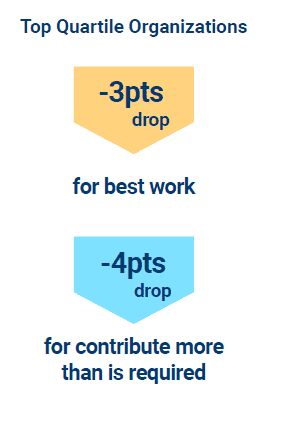

The delta is more noteworthy for organizations in the top quartile of our database, for whom “best work” declined by three points and “contribute more than is required” declined by four. The net impact is that within top quartile organizations, employees express a three-point-greater likelihood of doing their best work compared with going above and beyond. And for average organizations, the gap increases to four points.

Is It New?

No. The term is trendy and cute, but this is — at its core — employee engagement. For over 30 years we have seen employees who have pulled back on their engagement and, in turn, their performance, without necessarily exiting the organization. In some cases, they are in a “waiting to see what happens next” mode (e.g., “I’ll re-engage when I get promoted”); and in others it is just a decision to not fully lean in to work (for any number of reasons — but often because the experience isn’t rewarding them to do so).

Is It Bad?

Not necessarily. Having healthy boundaries is good. Prioritizing wellbeing is good. Realizing there’s more to life than work is good. But arriving at this point as a result of feeling burned out, taken advantage of or unheard is not.

Either way, here are some things organizations can do about it:

- Empower employees to (respectfully) push back when the ever-growing, “everything’s urgent” list of priorities starts to resemble Sisyphus’s boulder. Better yet, when it starts to resemble a pebble.

- Take vacations and be offline during that time. Yes, I’m speaking to executives here. If you don’t model this behavior, neither will anyone else. While you’re at it, review PTO usage in addition to overtime. If the former is low and the latter is high, fix it. Also review this data for employees who’ve left the organization.

- Forget work/life balance. And guard against “flexibility” as a wolf in sheep’s clothing (i.e., a lack of boundaries in the guise of doing employees a favor). Practice work/life separation. Off is off. At the end of the day, emails stop. Set an expectation that everyone uses technology to schedule emails for the next day’s work hours.

- Incorporate “Stay conversations” as a standard expectation for all people leaders to conduct with their direct reports. If managers don’t know what energizes individuals, you’re not only risking turnover but also likely losing out on some of your STRIVE potential.

- Don’t tolerate balance, celebrate it! Enable employees with shared interests to connect, solicit them to tell their stories internally and create kudos when employees do something interesting outside of the workplace, because it makes them more interesting people who’ll ultimately do more interesting work for you.

- Listen to your employees (and act on what they say). Go beyond “surveying” to truly listening. Although employees and their managers certainly have a role in creating a culture of engagement, it’s ultimately up to senior leadership to drive that culture and to drive the needed changes that are inhibiting employees from being all-in.

Employees aren’t being quiet, despite the trendy term. Unlocking the power of people and teams is possible when organizations know where and how to lean in and listen, and consistently follow through.

The article was first published here.

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash.

5.0

5.0