This interactive tracker aims to measure the progress and preparedness of ten key sectors on the path to achieving global net-zero emissions by 2050. It may be viewed as a contribution to the first global stocktake of progress against the Paris Agreement.

As the physical manifestations and socioeconomic impacts of a changing climate become increasingly visible across the globe, it is natural to ask what real progress is being made toward the goal set by the Paris Agreement to limit warming to well below 2ºC and ideally to 1.5ºC. Tracking global emissions provides a direct measure of this progress. It is, however, a lagging measure and says little about the future. Likewise, looking at individual trends can mask underlying complexities. For instance, the drop in the cost of renewables, while real and positive, is not necessarily sufficient on its own to ensure their global deployment.

To limit global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius above preindustrial levels, most transition pathways envision reaching net-zero emissions by about 2050. Tracking global progress is an important part of this effort, and emissions reduction is one key measure of this. But what about tracking the actions that trigger those reductions?

We believe that a more robust way of assessing progress is not only to measure emissions but also to examine the extent to which the underlying requirements for a net-zero transition are being met across categories, sectors, and geographies. Or, in other terms, to combine lagging and leading indicators. This helps us understand whether the world is “on track” (since emission reduction is a decades-long journey) and to identify key action areas that may need attention and acceleration.

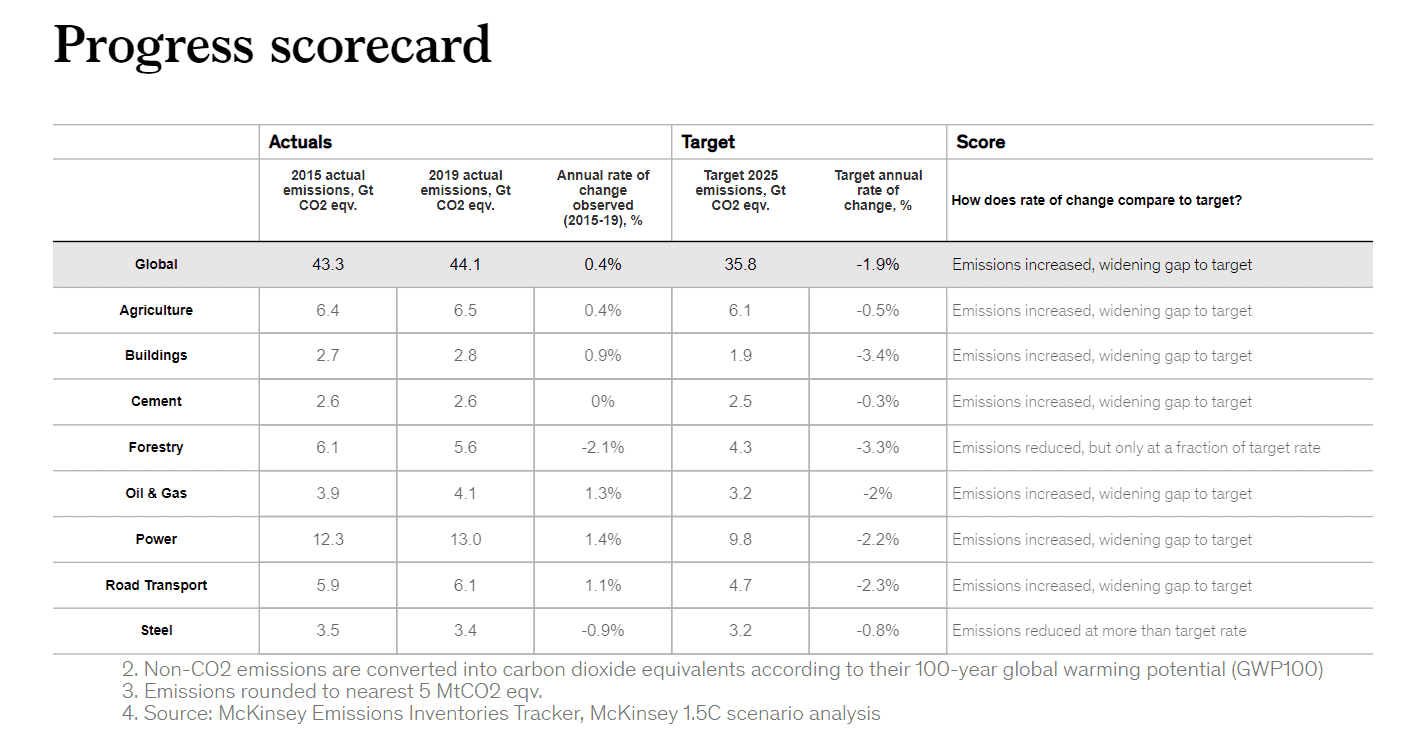

To this end, we have created a net-zero transition tracker.1 This initial release represents a beta version, which we hope to refine over time. The ten sectors featured in the tracker—power, road transport, maritime transport, aviation, oil and gas, steel, cement, buildings, agriculture, and forestry—were responsible for approximately 80 percent of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions in 2019.2 Each sector is ranked on two dimensions: progress and preparedness. The progress score assesses the rate of emissions reduction for each sector (Exhibit 1). The preparedness score ranks sectors according to the key requirements for a more orderly transition (Exhibit 2).

To explore the definitions used, methodology, limitations and potential improvements to this tracker, please see the sidebar below the interactive feature.

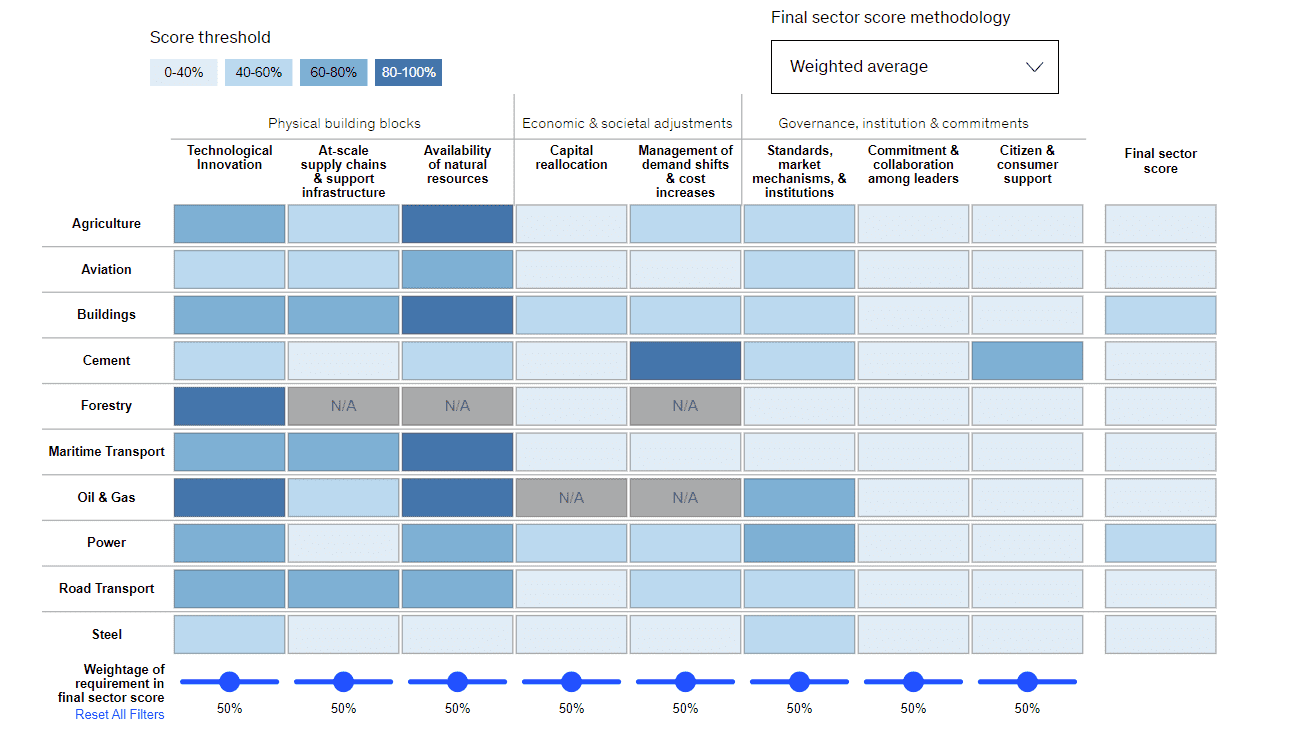

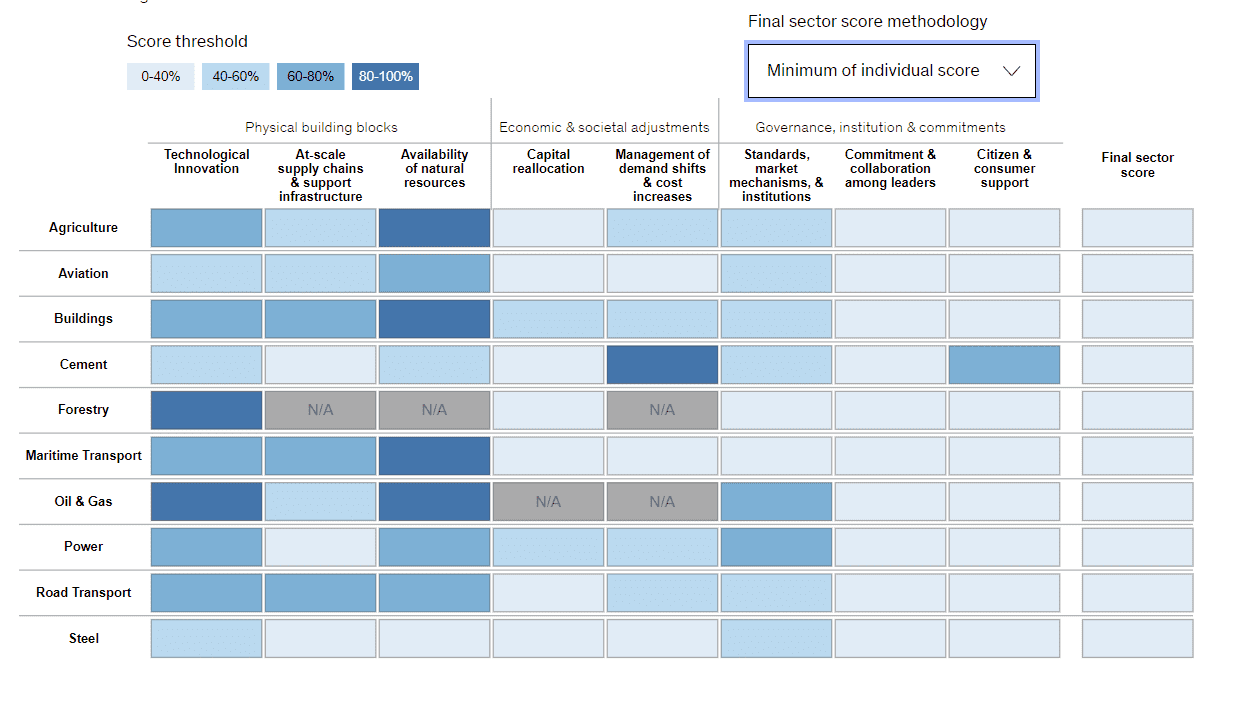

Preparedness Scorecard

This interactive feature enables you to explore the research in detail. Hover over each block for more information about the relevance or context of each scored dimension for the sector in question. Use the drop-down menu above the table to choose between two methodologies for scoring the sectors. Or adjust the sliders under each column to give scored dimensions more or less weight in the final sector score.

1. Requirement 6 (Compensating mechanisms to address socioeconomic impacts) is excluded from the preparedness analysis at the sector level. Socioeconomic impacts are experienced at a country or regional level. Correspondingly, the compensating mechanisms are seldom addressed at a sector or industry level, besides focused efforts such as reskilling. Note: This is an initial release of the net-zero transition tracker. It represents a beta version, which we hope to refine over time. For more information about the methodology, limitations and proposals for improvement, please see the sidebar.

Defining progress and preparedness

Progress is defined by comparing the annual rate of emission changes over the four-year period (2015–19) to the target annual rate of change over 2015–25. The choice of this timeline is to exclude the anomaly of the pandemic years; future versions of the tracker will consider the most recent period for which data is available. Emissions for each sector for 2015 and 2019 were sourced from the McKinsey emissions inventory tracker. Comparing these rates enables us to differentiate sectors with reductions in emissions from sectors with increases. The target rate of change was based on the McKinsey 1.5°C scenario analysis.

Preparedness is determined by an assessment of the prerequisites for each sector to stay on track for the transition, such as capital reallocation and consumer support for low-emission technologies. Scores range between 0 and 100 percent, where 100 percent represents the level that is required for a sector to progress along a 1.5-degree compliant net-zero pathway each year. A 100 percent preparedness score would mean that a given sector has in place all the elements needed to be on track for global net zero by 2050. Ideally, each sector would reach 100 percent preparedness every year in the approach to 2050.

Details on methodology

In developing the tracker we have made five main choices:

- We include both progress and preparedness measures. We track emissions reductions as the key measure of progress. To measure preparedness, we use the nine key requirements for a more orderly transition, assessing for each sector the extent to which these requirements are in place, compared to their required implementation level under a 1.5°C pathway. Each sector is evaluated on eight of the nine key requirements. We excluded one requirement—compensating mechanisms to address socioeconomic impacts—because the world is still in the very early stages of introducing such measures.As detailed above, emission scores are calculated by comparing the rate of emission changes over four recent historical years (2015–19) to the required reduction rate for 2015–25. This provides a positive score for sectors with reductions, while resulting in a negative one for sectors with increases in emissions. The more positive the score, the better it aligns with the required rate of reductions. For preparedness, we have defined four levels on a scale of 0 to 100 percent corresponding to the four quartiles (0 to 40 percent, 40 to 60 percent, 60 to 80 percent, and 80 to 100 percent). A score of 100 percent implies that a certain sector would be fully meeting all the input requirements for the current year, whereas a score of 0 percent implies the sector would be meeting none of the requirements.

- We provide a view relative to a specific net-zero trajectory. The tracker is based on a hypothetical path that would limit warming to a 1.5°C increase, relying largely on the Net Zero 2050 scenario from the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and the McKinsey 1.5°C trajectory, among other sources and expert input. For our progress indicators, we measure how closely our current rate of emission change compares to the required emissions change as per McKinsey’s 1.5°C trajectory.

- We rely on both quantitative data and expert insights. Progress is measured by a quantitative indicator, as described above. Preparedness scores are calculated by combining qualitative and quantitative inputs in ways that vary depending on the individual requirement.Qualitative assessments are sourced from a tailored survey of more than 40 McKinsey subject matter experts. Quantitative inputs are taken from publicly available databases that pertain to each requirement. Technological innovation, for example, is assessed using the International Energy Agency’s (IEA’s) technology readiness scale. Across progress and preparedness, we leverage six different quantitative indicators, including the IEA technology readiness scale, Climate Policy Initiative data on climate finance flows, and the Sixth Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.The combination of these inputs forms the sector score, which is then coupled with the sector’s emissions as a weight to determine global scores. As mentioned before, our emission progress scores rely on 2019 data to attempt to exclude the anomaly of the pandemic years. Most of our preparedness measures, however, use 2021 or 2022 data, although in some cases we have had to use data from slightly earlier years due to poor availability.

- We normalize each indicator to allow comparison across sectors and dimensions. Rather than evaluate sectors in isolation, our objective is to provide a suitable scale (0 to 100 percent) to compare across sectors on each of the preparedness requirements and to compare across requirements for each sector. This enables us to identify shortfalls across sectors for certain requirements and helps us evaluate progress in a global, integrated fashion by comparing today’s levels relative to the target trajectory for each requirement.

- We provide flexibility to the viewer to determine the weights of requirements to the aggregate sector score. In Exhibit 2, an equal weighting is applied by default to each factor to create an aggregate sector score. In the interactive version, however, the viewer is able to weight the relative importance of the various requirements on a scale of 0 to 100 percent. This relative weighting can either be guided by the specifics of a certain sector or by the viewer’s assessment of their relative relevance. For instance, a reader may view, say, the availability of financing or citizen support as a more dominant dimension and weight them accordingly.

We very much welcome questions and suggestions regarding the methodology.

Limitations of our methodology

It is important to highlight the inherent and practical current limitations of this effort, particularly the following four points:

- Many of the nine requirements are nontrivial to quantify and measure. For example, Requirement 7 seeks to measure the maturity of companies’ governance, tracking of climate impact, and institutional alignment of strategy with industry and other external organizations. This requires a multifaceted assessment of disclosures, governance maturity mechanisms, and alignment of strategy with public organizations. Our tracker only evaluates specific facets of this problem, and hence only provides a directional assessment. We believe, however, that our overall approach of combining quantitative data with expert inputs provides an acceptable initial perspective for a beta version.

- Latency in data availability creates a lag that is hard to bridge. As availability of current data is sporadic, and in some cases scarce, some of our data reflect a state of the world in 2020 or even 2019. As the data landscape improves over time, we expect to have decreased latency in future editions.

- The results, even if directionally intuitive, will appear more precise than they are. We have adopted a scale of 0 to 100 percent to compare preparedness relative to the required levels for a certain sector. However, both the methodology and the data have limitations. For example, our policy instrument adoption metric for Requirement 7 is limited to G-20 countries. We have chosen to only show the results by quartile rather than by percentages to avoid false precision. The readers should always bear in mind the natural limitations of any assessment method for such a complex question.

- Some sectors, due to their structural differences, demand a different approach than the others. We have decided to treat oil and gas and forestry differently from the other sectors. For oil and gas, the sector’s unique position in the energy industry puts it at the forefront of change, while simultaneously presenting a challenging proposition of gradual demand reduction over the course of the transition. For consistency with other sectors, we have decided to solely focus on Scope 1 decarbonization for oil and gas, as such decarbonization is necessary in any event and can be measured over the next few years. As we continue to improve the tracker, we plan to consider how to account for all sectors’ Scope 3 emissions. Similarly, for forestry we look at both its Scope 1 emissions and its carbon sequestration potential given the sector’s unique role.

Potential improvements

We see this tracker as a first version. We envision to improve it by implementing the following measures:

- Adding a larger number of quantitative metrics to requirement assessments (for example, price metrics for natural resources)

- Adding sources that are more comprehensive for existing metrics (for example, expanding our policy instrument adoption metric, part of our governing standards; tracking and market mechanisms; and effective institutions requirement, to cover all countries rather than just the G-20)

- Using new data tools to further enhance inputs (for example, leveraging AI to assess how a company’s transition exposure affects its stock prices, and thus reflects its ability to manage demand shifts and near-term unit cost increases)

- Leveraging an external network of experts to supplement qualitative inputs from McKinsey experts

Following on from our 2022 report “The net-zero transition: What it would cost, what it could bring,” we hope this tool becomes a useful resource in the quest to identify gaps, prioritize actions, and make headway in reaching the net-zero goal.

To assess Preparedness, each sector has been evaluated on 8 of the 9 requirements for an orderly transition to net zero. These scores are calculated by combining qualitative and quantitative inputs. Qualitative assessments are sourced from a tailored expert survey. Quantitative inputs are taken from publicly available databases. These inputs are combined to form the sector’s final score.

Initial Takeaways From Our Work

The world clearly lags behind in progress and preparedness, but the physical building blocks category of requirements shows promise. As we examine the results of this initial exercise, six key conclusions emerge that point to a need for urgent action and uncover gaps across sectors and requirements:

- The net-zero transition is not on track and the world is at risk of falling even further behind. Current rates of emission reductions show that substantial progress is still necessary relative to where sectors need to be today to reach net zero by 2050. Global preparedness to achieve the net-zero transition by 2050 seems to be at less than a third to half the level required under a relatively more orderly transition scenario for most requirements, when the criteria are weighted equally. It would be significantly lower if key dimensions such as financing are weighted more heavily. There are, however, pockets of relative strength within the nine criteria.

- Among the eight dimensions scored, technology innovation has the strongest position and is therefore not the gating factor. At the same time, technology is not fully on track either and remains in need of continued acceleration. We define this score using the IEA technology readiness scale, which assesses technologies on a score from 1 to 11, ranging from initial idea to proof of stability reached. Today, technological innovation measured based on this score is not the key bottleneck in most sectors. Indeed, we find that in six of the ten sectors, scores were at commercial demonstration phase or higher, corresponding to a preparedness score of 70 to 100 percent. These scores are based on linear translation of the IEA scale of 1 through 11 to a scale of 0 to 100 percent. When we re-weighted readiness levels to give more emphasis to the later deployment levels of 7 through 11, the scores for all sectors remained above 30 to 50 percent, meaning that progress on this dimension remained further advanced (albeit less so) than on others. Though this is positive, it is important to note that technology innovation measured using this metric does not necessarily equate to full technology deployment readiness. Deployment of technology requires systematic support across most of the requirements, including scalable supply chains, supportive financing, and many of the other requirements described here. It also requires the ability and willingness of companies and customers to support the transition, including via further technological innovation and other measures to bring down costs, close performance competitiveness gaps with traditional alternatives, and in certain cases the ability to shoulder additional costs. In all these areas, as some of our other requirement scores indicate, large gaps remain. Increasing momentum is crucial here to advance in areas where further innovation is needed and to spread technology maturity across all regions.

- The categories of economic and societal adjustments and of governance, institutions, and commitments appear to lag significantly behind the physical building blocks category. Indeed, all the underlying requirements in these two categories stand below the 50 percent mark in aggregate and for most sectors. The economic and societal adjustments category faces challenges on both dimensions measured; for example, significantly more financing may be needed for low-carbon technologies.

- On the dimensions with relatively higher scores, the challenge is to sustain and accelerate the momentum given rapidly rising needs. For example, the availability of natural resources appears to be relatively better than most other requirements, based on the amount needed for today’s levels of activity (though gaps still remain), but would need sustained action from private players to maintain momentum and meet future demand. To be on track for the net-zero transition by 2030 and beyond, supply ramp-up for eight out of nine key minerals would need to significantly accelerate.3 Unless these supply needs are met or viable alternatives are found, decarbonization efforts in many sectors may stall in the coming years due to supply bottlenecks or price flare-ups. Similarly, as discussed above, it is crucial to continue to innovate to lower costs on key technologies and decrease their dependency on scarcer raw materials.

- The dimensions with lower scores would still require a huge and concerted effort, particularly related to supply chain scale-up, capital allocation, and citizen and consumer support. The scale-up of supply chains, capital, and consumer support may need to be substantially accelerated to ensure resilience and avoid shortages and price spikes. Of particular concern are sectors critical for materials—namely steel, cement, and forestry—and for food production (namely agriculture), which have some of the lowest sector scores across all three requirements but especially on capital allocation and citizen and consumer support. It is especially important to manage the ramp-up of low-emissions power capacity and associated supply chains with the greatest care, as energy is central to the global economy and as the net-zero transition involves massive electrification of various end use sectors. Considering capital allocation, momentum has been increasing on climate investment ambitions, but our analysis suggests that climate finance flows have been disproportionately concentrated in the buildings and power sector. New financial instruments and asset classes (for example, venture capital investment in infrastructure, enhanced cross-border finance for developing economies) are needed at scale to drive the magnitude of capital required for the transition. Another area needing concerted action is support from citizens and consumers. Across all sectors, except for cement, which appears to have greater support due to falling operational costs of production from some transition technologies (for example, clinker substitution), experts believe that less than a quarter of consumers would be willing to pay any green premium. This is particularly concerning since citizen and consumer support can be viewed as the most foundational of all requirements. Companies will be faced with rising capital expenditures and operational costs as they transition to low-emissions alternative products. Much more work is needed across the globe to build broad-based support, manage any economic dislocations, and cushion the burdens of any cost increases, especially for the most vulnerable. This may involve concerted efforts toward better coordinated national industrial and energy strategies.

- There are immediate near-term actions stakeholders can take to reduce emissions and enhance resilience while driving a more orderly energy transition. We believe that, despite near- and longer-term challenges on the path to net zero, there remain a number of clear and immediate opportunities leaders can and should tap into now, in parallel with working on accelerating the transition. Such opportunities reduce emissions, are relatively easy to implement, and often lower costs and drive energy resilience. Examples include measures to enhance energy efficiency (for example, in the buildings sector or industry), driving circularity and thus reducing both energy and materials usage, and taking steps to limit methane leakages in ongoing fossil fuel production. Such measures are especially critical given the time it will take to raise sufficient amounts of capital (or reallocate capital) from high- to low-emissions assets across industries.

Hauke Engel is a partner in McKinsey’s Nairobi office; Mekala Krishnan is a partner in the Boston office; Daniel Pacthod and Humayun Tai are senior partners in the New York office; Hamid Samandari is a senior partner in the Washington, DC, office; Simran Khural and Mackenzie Murphy are consultants respectively in the Vancouver and Denver offices.

The authors wish to thank Pedro Assuncao, Ryan Barrett, Brodie Boland, Rory Clune, Nate Coursey, Francesco Cuomo, Thomas Czigler, Nicolas Denis, Jason Forrest, Alex France, Eric Hannon, Kersten Heineke, Gwyn Herbein, Duko Hopman, Ruth Huess, Kristen Jennings, Alex Kazaglis, Curran Kelleher, Bijan Kohler, Connor Kreb, Dhiraj Kumar, Lisa Leinert, Alexandre Lichy, Peter Mannion, Anna Massey, Ryan McCullough, Kelsey Nanan, Jesse Noffsinger, Dipti Pai, Gillian Pais, Dickon Pinner, Pradeep Prabhala, Sebastian Reiter, Demian Roelofs, Ole Rolser, Aditi Sahni, Mateo Salazar, Greg Santoni, Patrick Schaufuss, Robin Smale, Ken Somers, Gustaw Szarek, Bryan Vadheim, Shally Venugopal, and Markus Wilthaner for their contributions to this article.

The article was first published here.

Photo by Olivier Piau on Unsplash.

1.0

1.0