A new McKinsey Health Institute survey across 30 countries offers insights into how organizations can help create a workplace that prioritizes physical, mental, social, and spiritual health.

At a glance

- Holistic health encompasses physical, mental, social, and spiritual health. The McKinsey Health Institute’s 2023 survey of more than 30,000 employees across 30 countries found that employees who had positive work experiences reported better holistic health, are more innovative at work, and have improved job performance.

- For employees, good holistic health is most strongly predicted by workplace enablers, while burnout is strongly predicted by workplace demands. Providing enablers alone will not mitigate burnout, and addressing demands alone will not improve holistic health. A complementary approach is needed.

- Organizational, team, job, and individual interventions that address demands and enablers can boost employee holistic health. These may include flexible working policies, leadership trainings, job crafting and redesign, and digital programs on workplace health.

For most adults, the majority of waking daily life is spent at work. That offers employers an opportunity to influence their employees’ physical, mental, social, and spiritual health.

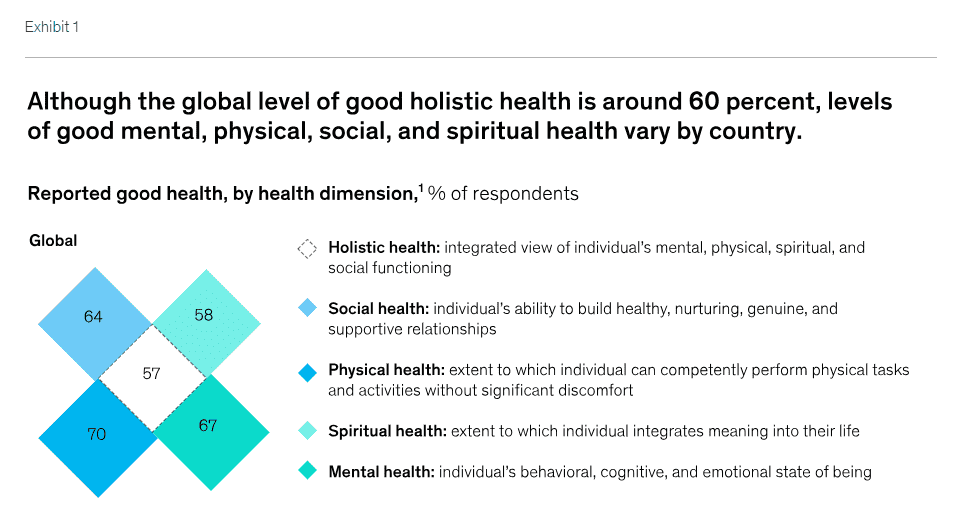

To support the move to better health, the McKinsey Health Institute (MHI), along with other organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), are highlighting a more modern way to view health beyond illness and its absence.1 Embracing the concept of holistic health—an integrated view of an individual’s mental, physical, spiritual, and social functioning2—is a vital step toward “adding years to life and life to years” across continents, sectors, and communities.

Previous research from MHI has focused on how modifiable drivers of health can lead to healthier, longer lives. The majority of these—ranging from quality of sleep to time spent in nature—sit outside of the traditional healthcare system, and many of these drivers could benefit from employer support. MHI’s new survey of 30,000 employees across 30 countries explores how employees perceive their health and how workplace factors may act as demands upon or enablers to mental, physical, spiritual, and social health.

The reasons to act go beyond improving health. Recent McKinsey research finds that employee disengagement and attrition—more common among workers with lower well-being—could cost a median-size S&P company between $228 million and $355 million a year in lost productivity.3 Research by MHI and Business in the Community showed that the UK economic value of improved employee well-being could be between £130 billion to £370 billion per year or from 6 to 17 percent of the United Kingdom’s GDP. That’s the equivalent of £4,000 to £12,000 per UK employee.4

In the MHI Holistic Health framework and research model,5 we demonstrate the additional value of measuring holistic health over and above other popular health-related outcomes such as burnout or other well-being-related outcomes such as engagement or happiness. The insights presented in this article are vital for organizations determining where to start when aiming to improve employee health and how to enable them to start considering, measuring, and improving holistic health.

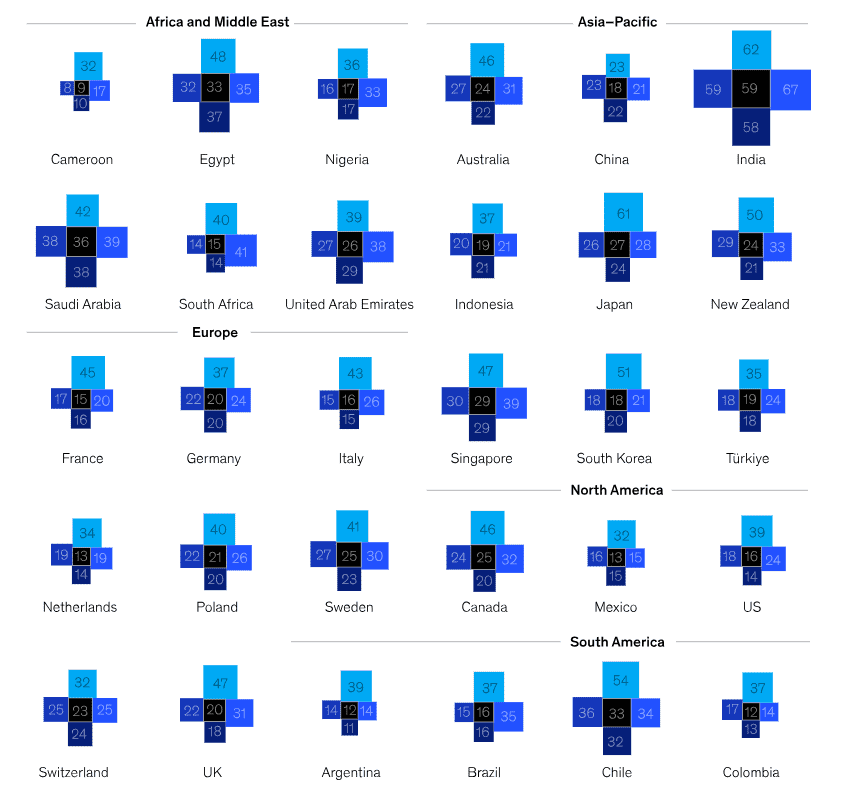

The Majority of Employees Report Positive Overall Holistic Health

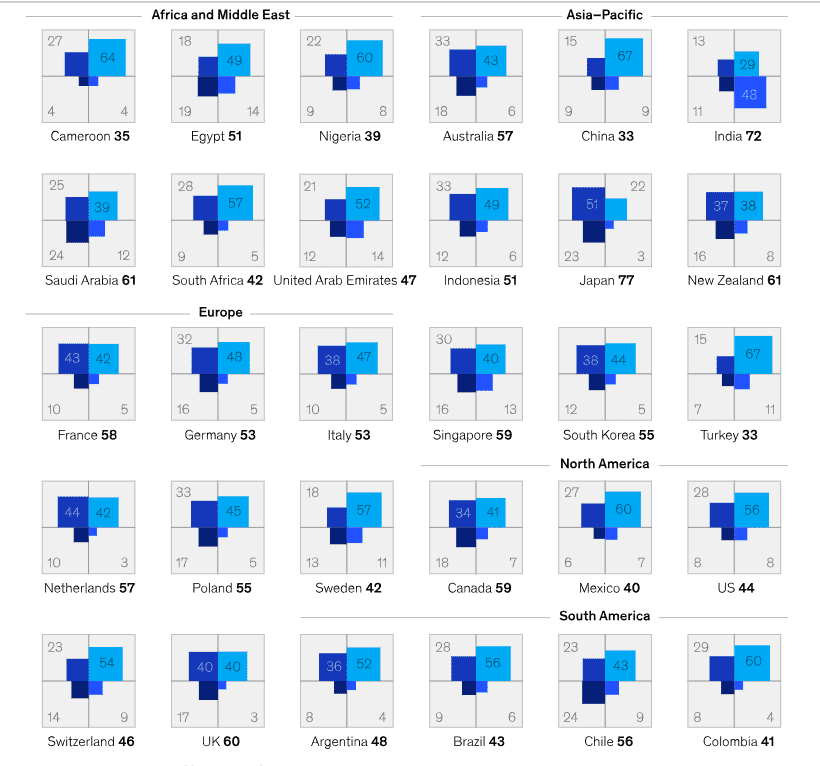

We found that more than half of employees across 30 countries reported positive overall holistic health6—but there are substantial variations between countries, with the lowest overall percentage of positive scores in Japan (25 percent)7 and the highest percentage of positive scores in Türkiye (78 percent). Among respondents, the largest proportion of positive scores was for physical health at 70 percent, and approximately two-thirds of global employees reported positive scores on mental and social health. The lowest proportion of positive scores were on spiritual health, at 58 percent.

When looking at demographic differences and nuances, those aged 18 to 24 had the lowest holistic-health scores. This complements previous MHI work on the challenges facing Gen Z. For companies, size matters: respondents in larger companies (more than 250 employees) had higher holistic-health scores than those in smaller companies. Within role, managers had the highest holistic-health scores, while all other workers reported lower holistic health. Further, there are similar levels of good holistic health across the industries surveyed (Exhibit 1).

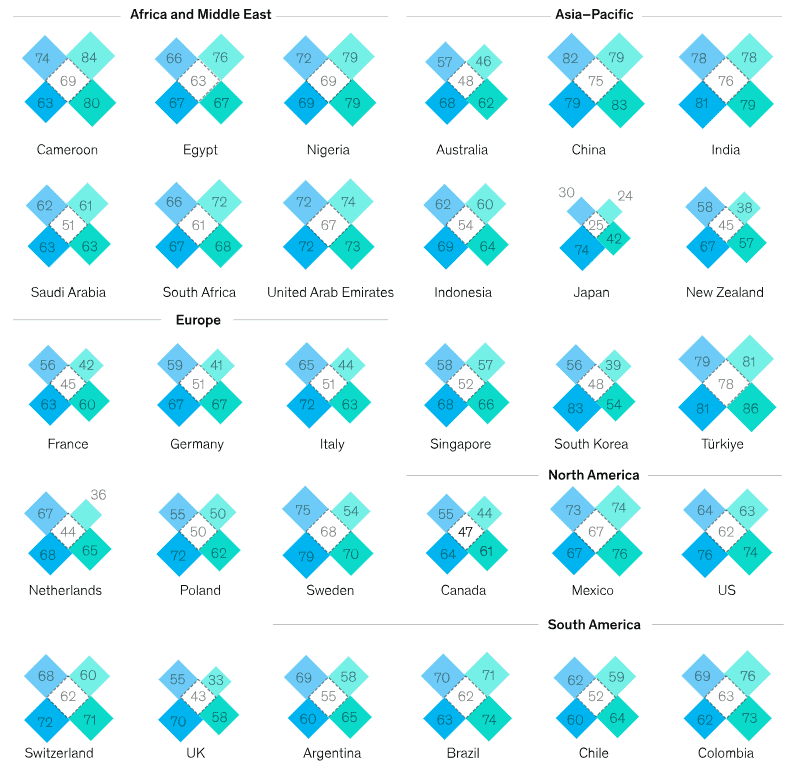

At a country-specific level, factors such as burnout symptoms, emotional impairment, or cognitive impairment vary. However, one common finding is a lack of energy: more than a third of respondents in 29 of the surveyed countries reported exhaustion. Comparatively, only three countries had a third or more respondents reporting mental distance or reluctance to work (Exhibit 2).

Understanding Demands and Enablers for Employees

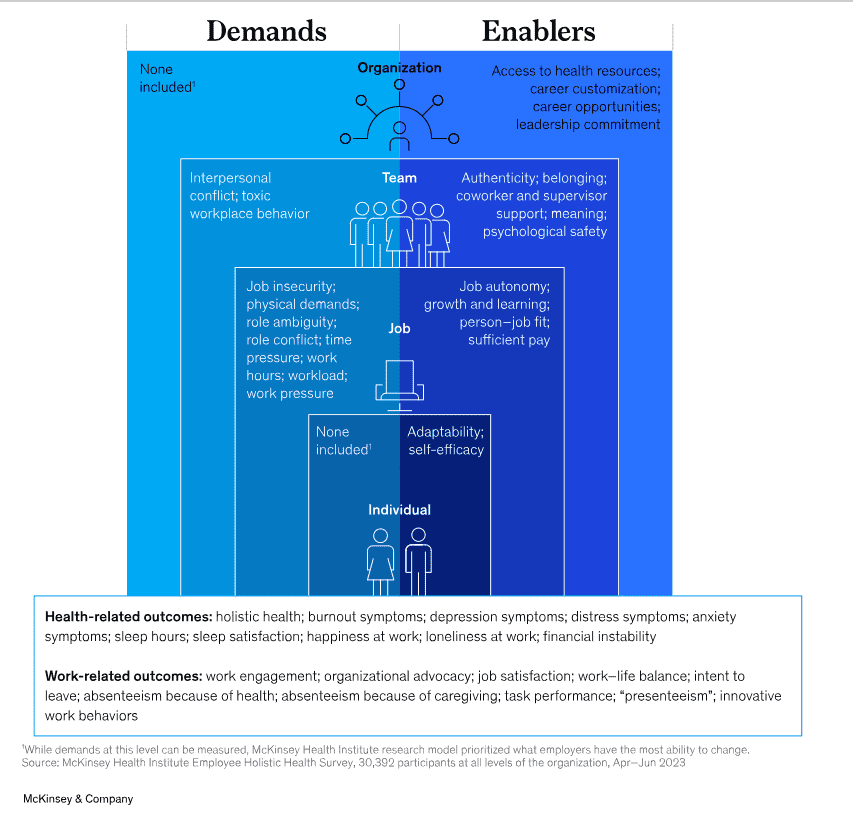

In this survey, MHI explored a wide set of demands, which are workplace factors that require sustained cognitive, physical and/or emotional effort, and enablers, which can offset job demands.8 Demands can be thought of as challenges in the workplace, and enablers help to effectively offset challenges, allowing employees to move forward and experience positive growth and development.

Our research model explores how these demands and enablers influence several work-related and health-related outcomes (see sidebar “What we measured”). Building on previous research, we now consider a vital new aspect: the relationship between demands, enablers, and an employee’s holistic health.

From April to June 2023, the McKinsey Health Institute conducted a global survey of more than 30,000 employees in 30 countries (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Cameroon, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Egypt, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, and United States). The dimensions assessed in our survey included toxic workplace behavior, interpersonal conflict, workload, work hours, time pressure, work pressure, physical demands, role conflict, role ambiguity, job insecurity, access to health resources, leadership commitment, career opportunities, career customization, psychological safety, supervisor support, coworker support, authenticity, belonging, meaning, job autonomy, remuneration, person–job fit, learning, and growth. Individual self-efficacy and adaptability were also assessed (exhibit).

The role of these dimensions were tested to determine whether they were associated with several health-related outcomes (holistic health, burnout symptoms, depression symptoms, distress symptoms, anxiety symptoms, sleep hours, sleep satisfaction, happiness at work, loneliness at work, financial instability) and several work-related outcomes (work engagement, organizational advocacy, job satisfaction, work–life balance, intent to leave, absenteeism health, absenteeism caregiving, task performance, presenteeism, and innovative work behaviors).

Exhibit

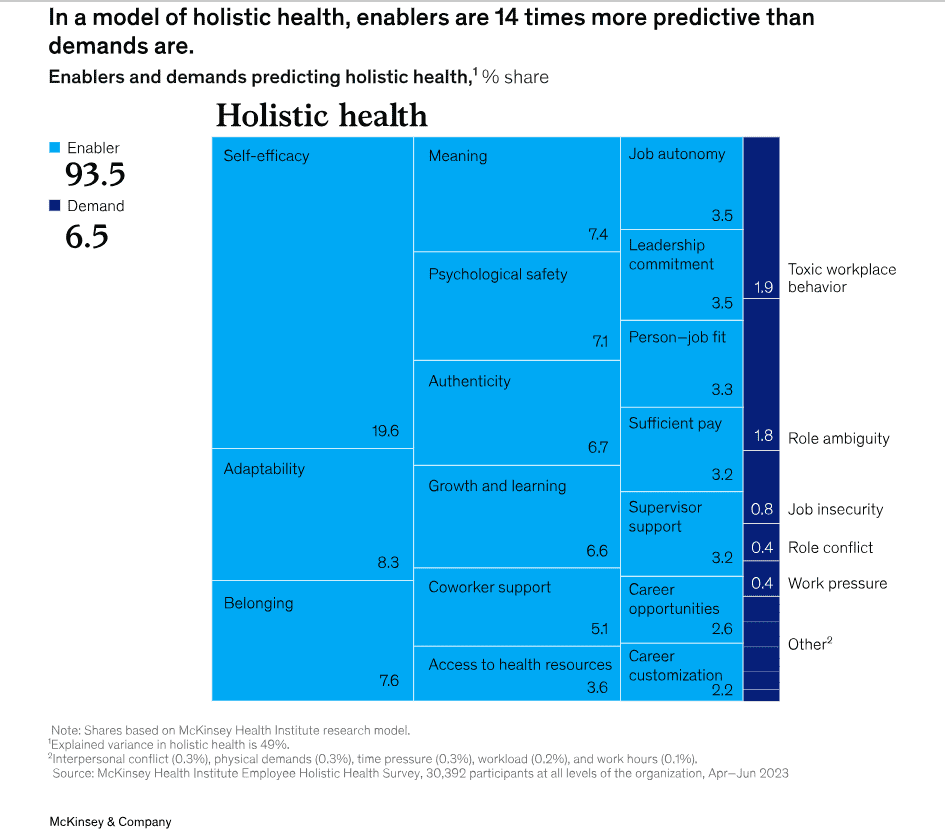

The MHI model predicted a large proportion of the variance in holistic health, at 49 percent, well exceeding traditional research models’ predictions regarding variance in outcomes.9 The higher the explained variance, the better positioned the model is to be able to reliably predict differences between employees’ outcomes. Interestingly, we find that as scores on one subdimension of health increase, scores on all subdimensions of health rise.

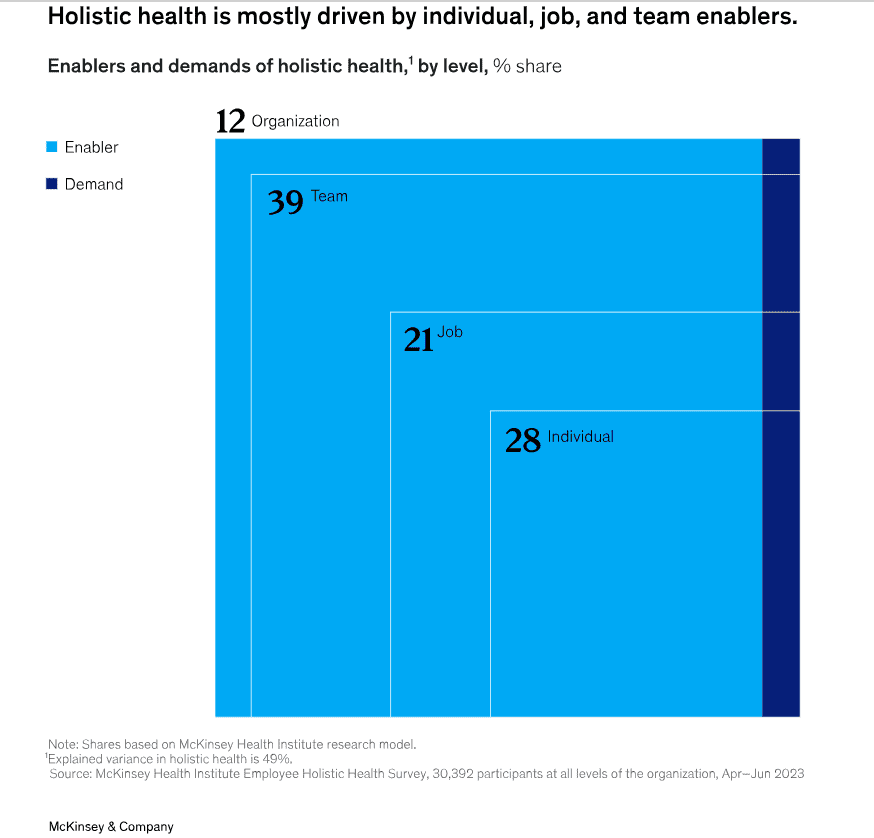

Enablers—aspects of work that provide positive energy such as meaningful work and psychological safety—explain the most variance in holistic health. Those who find meaning in their work and feel they can raise new ideas or objections with their coworkers are more likely to feel they are in better health across all four dimensions (Exhibit 3).

Holistic health also offers insight into workforce performance. For example, employees with good holistic health are more likely to indicate that they are innovative at work, have better work performance, and experience better work–life balance.

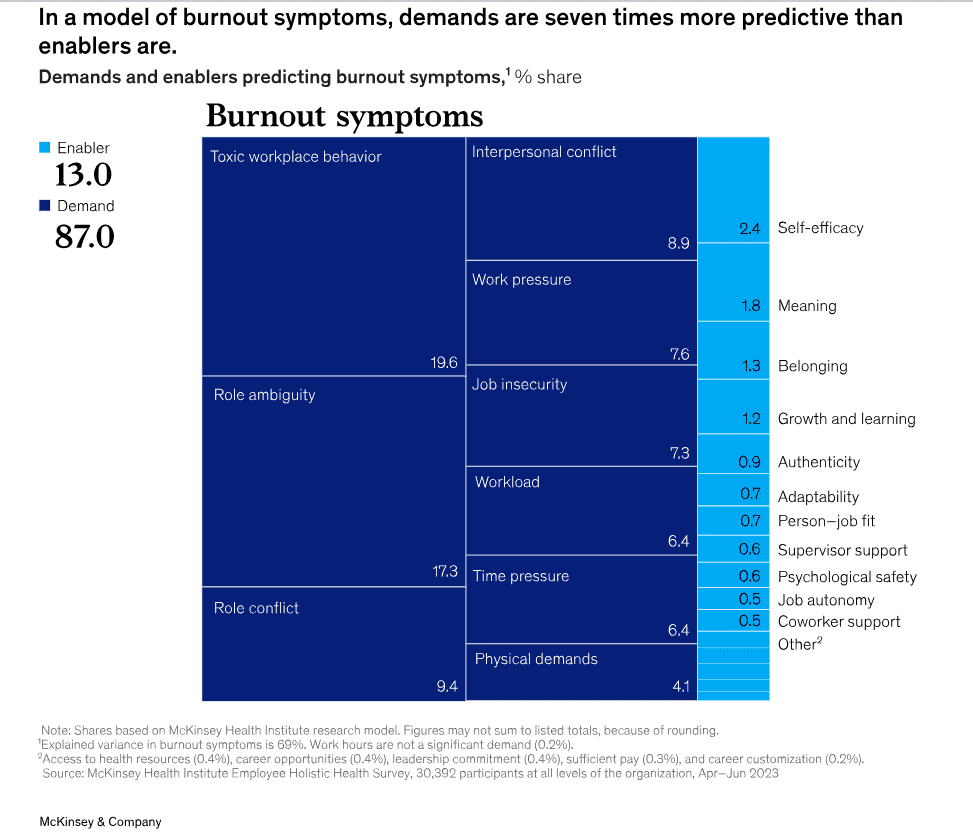

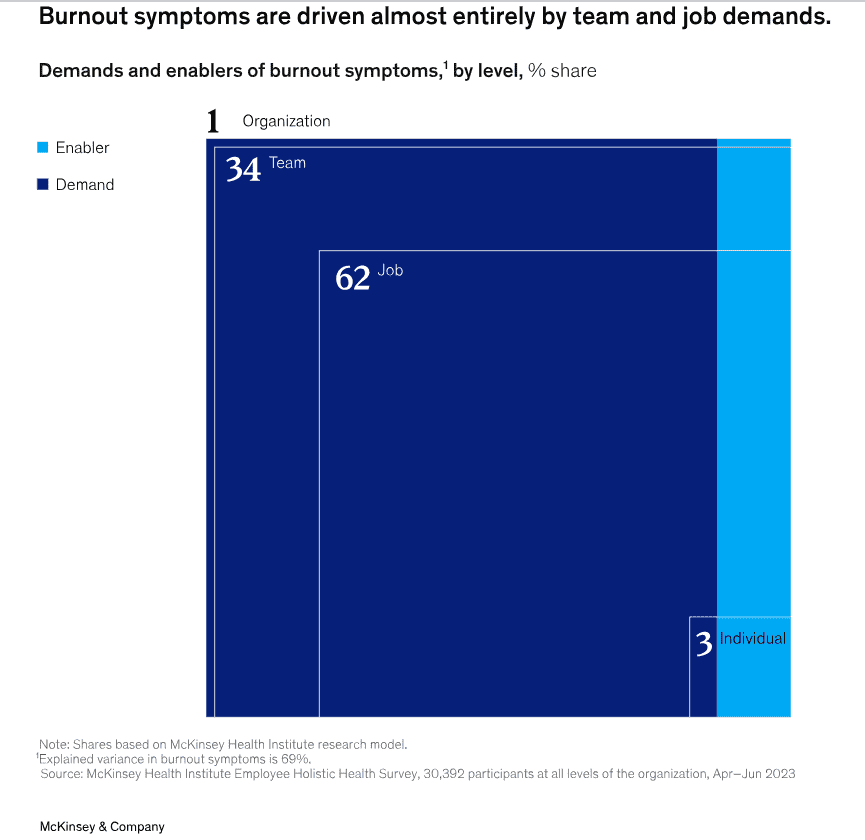

When examining burnout symptoms, demands—such as toxic workplace behavior, role ambiguity, or role conflict—are seven times more predictive than enablers are.

Team-, job-, and individual-level drivers affect holistic health (Exhibit 4). This means that workers who have confidence in their ability to do good work, are adaptable during changing working conditions, and feel as though they belong to a community at work have improved holistic health.

Team- and job-level drivers affect burnout symptoms. This means that workers who are excluded, bullied, or receive demeaning remarks from colleagues or who are unclear on what is expected of them at work have higher burnout symptoms.

The Relationship Between Holistic Health and Outcomes

Holistic health uniquely contributes to the prediction of several work-related outcomes, over and above related concepts such as burnout symptoms, engagement, and happiness at work. This highlights that the underlying components of health, while correlated with other workplace measures, are not equivalent to engagement or happiness at work.10

Holistic health is a strong measure of how an employee can sustain growth over time, which contributes to positive workplace performance. Having employees with strong holistic health has implications beyond short-term business performance. Community engagement beyond work is one example: when employees are suffering from poor holistic health, they are likely unable to help their communities. Relatedly, they may create a strain on health services through delaying care. This also could have implications for the role employers play in their communities—and for cities that are trying to foster good physical health and grow societal participation and purpose-driven initiatives among residents. Furthermore, employees who have strong holistic health may want to—and are better able to—work longer, which will be important for how employers approach an aging workforce.

How Burnout Symptoms Factor into Health

Consistent with our previous research on burnout, we found that 22 percent11 of employees are experiencing burnout symptoms at work across the 30 countries included in our study, although there are substantial variances between countries. Cameroon respondents reported the lowest rates of burnout symptoms (9 percent), and India respondents reported the highest rates of burnout symptoms (59 percent).12 When exploring demographic differences on burnout, we find younger workers aged 18 to 24, employees from smaller companies, and all workers who are non-managers report higher burnout symptoms.

Our survey findings underscore a critical pattern: demands—aspects of work that require energy such as dealing with toxic behaviors or role ambiguity—explain the most variance in burnout symptoms.13 But burnout is only the starting point: employers have a critical role to play in addressing a range of negative (mental) health outcomes at work beyond burnout.

It’s time to reframe how we think about employee health. Employers need to support the health of all employees—supporting those in ill health, taking preventative measures to avoid negative health outcomes, and actively building a work environment where more employees have positive holistic health.

Improving Holistic Health and Burnout Together

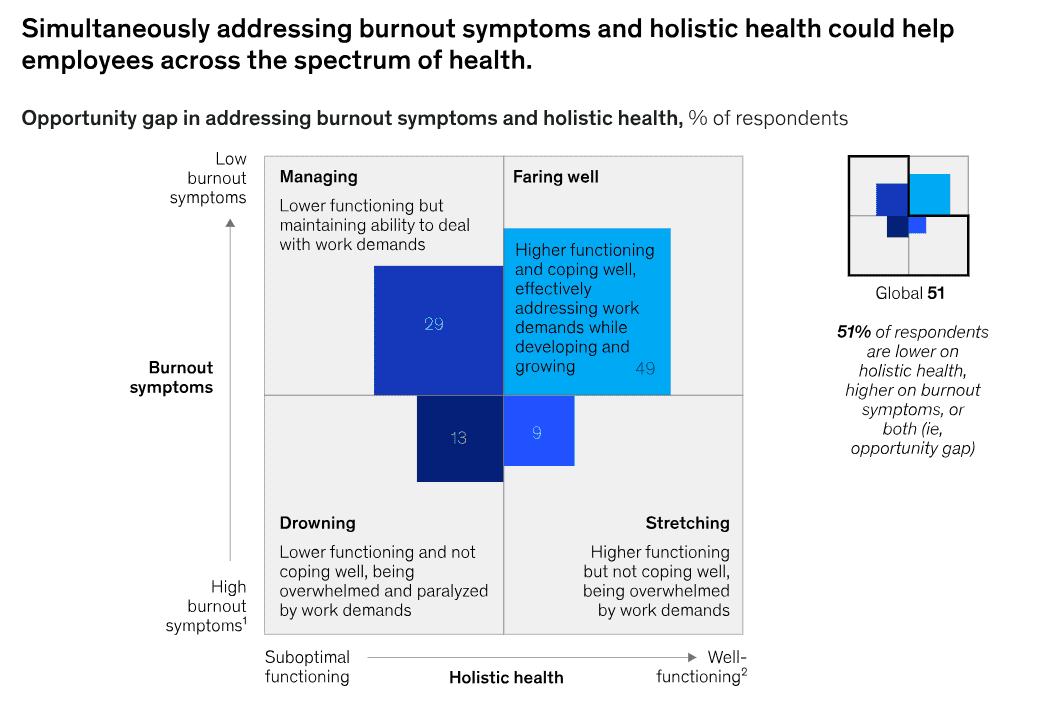

MHI explored how workers across our global sample were faring on both holistic health and burnout symptoms in the 30 countries we surveyed (Exhibit 5). The presence of positive holistic health doesn’t mean absence of burnout symptoms. They are negatively correlated but aren’t two opposite sides of the same spectrum. Burnout and holistic health can coexist.14

Exhibit 5

At the global level, we found approximately half of employees (49 percent) are “faring well”—well functioning across the dimensions of holistic health and simultaneously experiencing low rates of burnout symptoms. However, an average of 9 percent of employees are “stretching”—well functioning across the dimensions of holistic health and simultaneously experiencing high rates of burnout symptoms. Almost a third of employees are “managing”—experiencing suboptimal functioning across the dimensions of holistic health and experiencing low rates of burnout symptoms. The group struggling the most are those employees who are “drowning”—experiencing suboptimal functioning across the dimensions of holistic health and high rates of burnout symptoms. Exhibit 5 shows the percentage of employees that can be improved by simultaneously addressing demands and building enablers for employees. We call this the opportunity gap.15

Looking at holistic health and burnout symptoms together could help employers in different sectors better differentiate the true drivers of outcomes. For example, physicians, nurses, teachers, and others in the social or healthcare sectors often report finding meaning in their work, yet often also report high rates of burnout symptoms and consideration of leaving their jobs.16

Driving Organizational, Team, and Individual Action—Where to Start?

We uncovered drivers that are most strongly associated with positive and negative employee health outcomes. Our research insights suggest a set of actions addressing the workplace demands that fuel poor health and those that build up the workplace enablers to help employees thrive.

Workplace factors at the individual, team, and job levels have the strongest influence on holistic health. In our model, workplace factors at the individual level predict 28 percent of differences between employees on holistic health, while those at the job level predict 21 percent, team level 39 percent, and the organization level 12 percent.17

Comparatively, when looking at employees on burnout symptoms, in our model, workplace factors at the individual level predict 3 percent of differences between employees on burnout, while those at the job level predict 62 percent, team level predict 32 percent, and the organization level predict 1 percent. Ninety-four percent of the explained variance is driven by factors at the job and team levels.

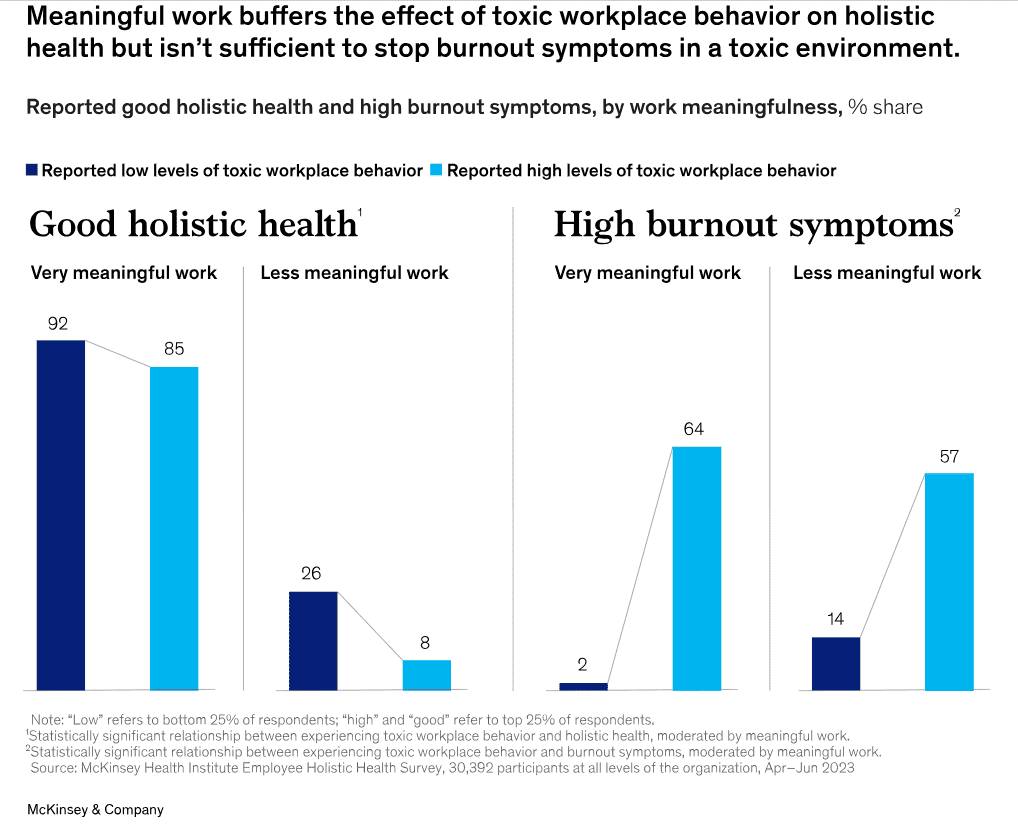

Employees who find their work meaningful more often report having better holistic health, even when they tolerate toxic workplace behaviors. But there is a limit. While holistic health can be maintained in a highly toxic work environment if an employee finds their work meaningful, meaningful work doesn’t protect against burnout symptoms in highly toxic environments (Exhibit 6). Furthermore, when employees experience toxic behavior at work, their holistic health scores are 7 percent lower and they report a 62 percent higher rate of burnout symptoms.

Exhibit 6

In simple terms, if employers want to improve holistic health, they need interventions at all four levels (individual, job, team, and organization). If employers want to reduce immediate negative outcomes such as burnout, then focusing interventions at the job and team levels are the best place to start.

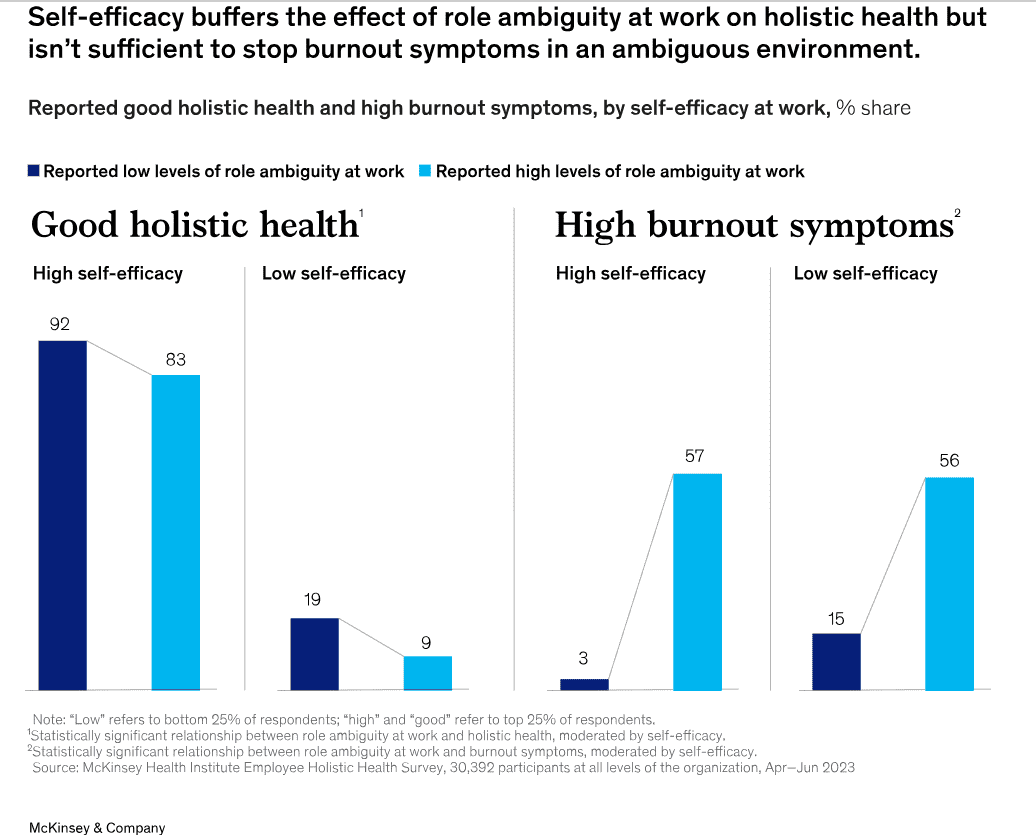

Consider an employee who may be described as “rolling with the punches” or “able to handle what we throw at her.” Those can manifest as self-efficacy and affective adaptability, both of which are the top two drivers of holistic health—meaning they are unique workplace factors that can improve holistic health in a targeted way. When employees have self-efficacy, they feel confident they can deal efficiently with unexpected events or handle unforeseen situations thanks to their resourcefulness. They feel they can remain calm when facing difficulty because they can rely on their coping abilities.

Employees with adaptability can stay relaxed even if they must change plans, get energy from unexpected changes, enjoy it when their situation changes, and enjoy unexpected events. It should be no surprise that when challenges or uncertainty arise, these employees fare better in terms of health—an effect also seen in our previous research on burnout.18 Employees with self-efficacy or adaptability skills report better holistic health, regardless of which demands they face (for example, high role ambiguity), perhaps because they are more capable of transforming challenging situations into opportunities. These are trainable skills that can be developed.19

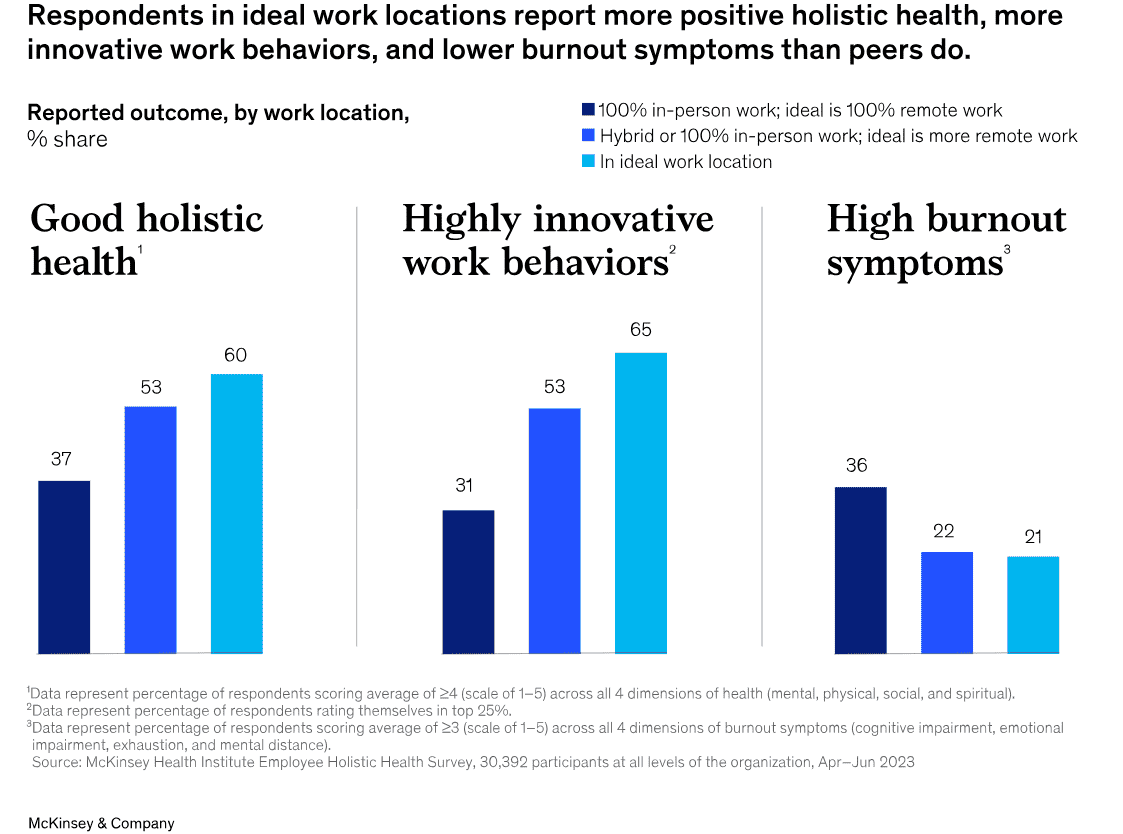

Our research indicates that when employees are working in their preferred work locations, they have better holistic health, lower burnout symptoms, and are more innovative at work. As the size of this gap between where they’re currently working and where they ideally want to be working increases, these effects are stronger, with larger gaps indicating lower health and innovation for employees (exhibit).

While self-efficacy can help maintain an employee’s overall sense of holistic health in a stressful environment, there is, again, a limit to which one can protect their health in these situations. While confidence in one’s ability to perform can protect their sense of holistic health, it doesn’t protect them against experiencing burnout symptoms in highly stressful environments (Exhibit 7). These findings suggest the best place for organizations to start may be addressing demands and building enablers for employees at both the team and job levels simultaneously.

It’s important to note that some ebb and flow of demands and enablers within an organization is inevitable. When committing to long-term change, it’s reasonable that organizations will undergo some episodic demands: for example, a seasonal rush at a retailer may create more short-term demands in an organization. Other organizations may have challenging teammates on temporary assignments. The MHI Holistic Health framework20 takes this into account, exploring how multiple levels of influence can encourage positive action around employee health and well-being—organizational, team, job, and individual—and emphasizes how overweighting on only reducing demands or building enablers, over the long run, can affect employee health.21 (For more on understanding work location and employee health, see the above accordian “Does work location influence health outcomes?”)

Employers Must Commit to Supporting Employees to Move from Ill Health to Positive Holistic Health

Improving holistic health at work can start with the following interventions:

- Understand the current state of holistic health in your organization. Establish a baseline for employee health and well-being, including identifying specific opportunity areas, before investing in targeted initiatives. This will ensure that the impact of your investments can be measured and that you are focusing on the areas producing real results. This can be done using existing surveys if they are scientifically sound. The McKinsey Health Institute’s (MHI’s) Employee Mental Health and Well-being assessment (available on our Employee Health Platform) is one option which is fully psychometrically validated and free of charge to deploy.

- Develop a comprehensive intervention strategy. Ensure that your organization invests in interventions that proactively address demands before employee health and well-being become an issue, and provide reactive support once they have already taken a negative turn. For example, offering additional days of leave for colleagues experiencing mental health emergencies can be helpful, but it does nothing to avoid the escalation of mental health challenges in the first place—especially if those challenges are aggravated by workplace factors. Interventions should also target all levels of the organization, with a focus on teams as the primary body that influences workplace experience. Many companies overindex on interventions targeting individual employees, putting additional responsibility on them to manage their holistic health on top of existing workplace demands. For example, providing employees with access to a meditation app is a valid intervention to support mental health, but it doesn’t address structural issues in the workplace or within team dynamics that may compromise it in the first place.

- Implement and track your intervention strategy. Start with a pilot group to test an intervention’s effectiveness before committing to a full-scale rollout. We recommend using the same survey used to baseline the organization to retest the pilot group a few months after deploying the intervention. This allows you to clearly measure the intervention’s impact on the opportunity areas identified through the baseline assessment before deciding if it’s worth rolling out to the rest of the organization. It’s critical to track how your organization performs against clear outcomes over time to monitor improvement and justify your organization’s continued investment in your intervention strategy. Choose a senior level leader with accountability to deliver the intervention (preferably someone other than the chief human resource officer) to link your intervention strategy to the business and support successful implementation.

- Ensure holistic health is part of how your organization defines success. Once employee health is a part of your organization’s value proposition, it should be backed by measures to ensure the organization stays accountable. This can take the form of management KPIs, nonfinancial reporting, or internal incentive structures. For example, management incentives and career development should be aligned with the holistic health outcomes of their teams. Likewise, leaders should model the organization’s values and working norms to support lasting change. All leaders should be able to communicate why and how they are embracing a modern understanding of health to convince employees they are truly “walking the talk.” This requires substantial investment and patience to see the results, as well as buy-in from leaders. However, our research indicates real long-term value regarding employee work-related outcomes. Research also indicates financial outperformance for companies prioritizing employee well-being.1

In this article, MHI has presented a compelling case for organizations to reduce employee burnout symptoms and increase holistic health. Our research suggests team- and job-level demands and enablers are the place to start for improving employee health within an organization (see the accordian above “Designing interventions to improve holistic health”). As employers develop strategies to fuel employee health and well-being, beyond focusing only on addressing poor mental health amid a challenging macroeconomic environment, it may be useful to examine how to support health at four different levels within an organization:

- Organization:

Organizational-level resources are often needed to support team-, job-, and individual-level interventions—and investment in holistic health must be supported by executives to have an effect. For example, interventions that encourage team members to act positively toward each other may fail if an organizational culture and performance system normalizes mistreating colleagues.

Second, job redesign starts from the top—while managers can help employees in job crafting and shaping, organizations that have policies that don’t support rotations or lateral mobility within an organization can undermine the effects of such interventions. Finally, while jobs should be designed with adequate compensation and benefits in mind, organizations are ultimately responsible for funding and delivering on these employee benefits.

Some examples of organizational-level actions include enrolling in living wage programs, pledging to ensure base pay is sufficient for all employees to cover their basic needs,22 offering financial programs in which employees can receive part of their pay prior to payday, providing access to remote medical care, or offering additional support or leave time for parents and caregivers.

- Team:

Our research highlights the important role team dynamics play in health and well-being—often the responsibility of managers and team leads. Team leaders should be trained appropriately and enabled to create healthier workplaces. In turn, they should then be held accountable for the ways they interact with others on their team and within the organization, the way their team members interact with each other, and they must intervene when employees treat each other negatively.

Interventions that promote positive behaviors and limit negative ones can help to build a team and organizational climate that promotes holistic health. Such interventions include but are not limited to manager trainings on creating psychologically safe environments and conflict resolution skills,23 implementing anonymous HR reporting systems,24 and incorporating confidential upward feedback on leadership behaviors and team well-being as input for performance reviews and promotions.25

- Job:

Job redesign or fine-tuning for sustainable work is one of the most direct ways to reduce demands at the job level, where organizations rearrange tasks with the goal of helping employees maintain their efficiency and health over time. This is often led by or facilitated from the top.

A broad range of additional interventions can help organizations set sustainable working norms. These include setting maximum working hours (per day, per week),26 limiting work communications to certain hours of the day, and providing multiple start times or self-scheduling options for shift workers. For example, Shopify recently canceled all recurring meetings of three or more people in their organization as a reset to ensure intentionality of recurring meetings and to make time for focused work.27

Another consideration for job design is whether those in certain roles are provided with adequate pay and benefits to cover their basic needs. Our research shows that those who can’t meet their basic needs with their pay feel more financially insecure and less holistically healthy than those who feel they are sufficiently paid. Employers may also examine what is covered for employees by health insurance, either public or private, and what requires out-of-pocket expenses.

- Individual:

Our research shows that having meaningful work is one of the key drivers for holistic health. Organizations can support their employees to find meaning in their work by being mission-driven, integrating their purpose into their business strategy and throughout the whole organization. Patagonia, for instance, focuses on hiring employees who are excited about the mission of “Patagonia is in business to save our home planet.”28

Involving employees in customizing their roles and careers—for example, through job crafting—has also been found a strong way to motivate, build capabilities, and help employees find meaning in the work they do. Other examples are capability training to help develop self-confidence and adaptability skills. Last but not least: middle managers of today and tomorrow will have an increasing pivotal role for business success,29 helping them get better equipped for the new world of work—including as people leaders—is not only nonnegotiable, it will also support fostering a supportive growth culture that builds employees’ holistic health.

Enabling a healthy workforce is no longer a luxury but rather a strategic imperative for organizations to navigate turbulent times in an ever more complex society. To seize the opportunities presented by employee health and well-being, employers must recognize their role. By agreeing to create workplaces where employees can thrive, organizations can prioritize holistic health as an important outcome that potentially aligns with an organization’s broader environmental, social, and governance (ESG) framework. Employers can take action by understanding how demands and enablers affect employees at various levels: organizational, team, job, and individual. As ESG metrics are increasingly used by investors as a decision measure for where to allocate their capital, we expect more research that could link employee well-being to financial performance.30

To truly understand what moves the needle on employee health, organizations should take a systemic approach to employee health that considers demands and enablers of employees, but also how they can design interventions at the organizational, team, job, and individual levels. For organizations, it’s no longer enough to consider employee health a soft metric. Rather, executives should consider employee health a part of leading by example, showing how better health and better business practices can allow everyone to flourish.

Jacqueline Brassey is a senior knowledge expert in McKinsey’s Luxemburg office, Brad Herbig is an associate partner in the Philadelphia office, Barbara Jeffery is a partner in the London office, and Drew Ungerman is a senior partner in the Dallas office; they are all coleaders in the McKinsey Health Institute.

The article was first published here.

Photo by Dan Meyers on Unsplash.

5.0

5.0