Business units that are underperforming or that do not align with strategy need to be addressed while also focusing on core businesses.

- What difficulties do CEOs face when deciding whether to fix, sell or close an underperforming business?

- How can Boards move from avoidance to action with an underperforming business?

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the pace of global change, and organizations need to adapt quickly if they are to survive. Business units that are draining cash or that do not align with strategy need to be addressed.

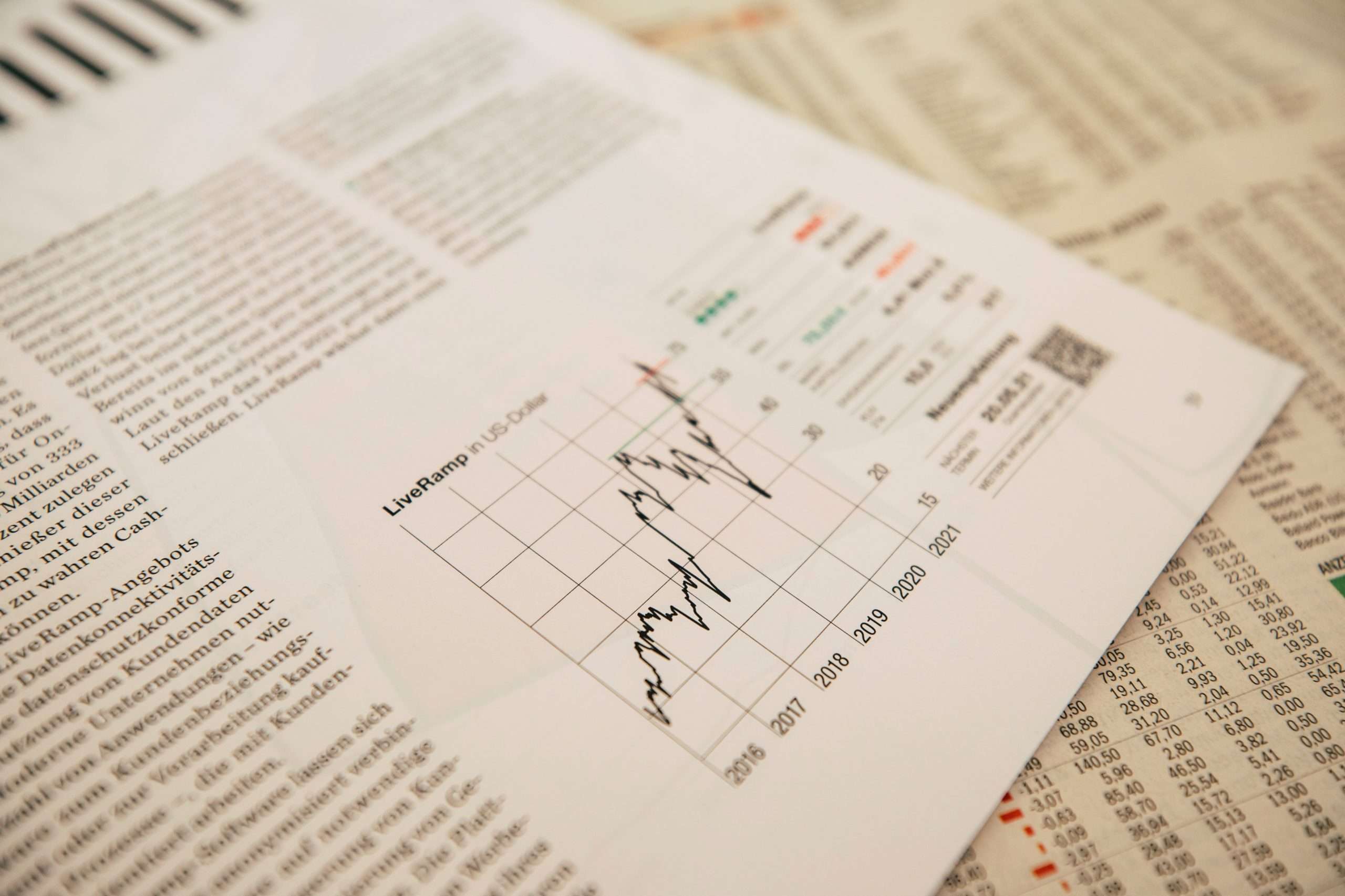

Sometimes, it’s the toughest decisions that don’t get made. But, as the COVID-19 crisis illuminates the challenges and opportunities ahead, the need for action is clearer than ever. According to our 2021 EY Global Corporate Divestment Study, more than three quarters (76%) of companies expect the continuing affects of the pandemic to accelerate their divestment plans.

Even before the pandemic, global organizations were facing unprecedented disruption on multiple fronts, from US trade relations with China to Brexit. As a result, global footprints and capital allocations are being reassessed. Additionally, there is a technological transformation underway and whole industries are reshaping, from automotive manufacturers adjusting to the future of mobility to energy companies managing the transition to a low-carbon future.

Now the COVID-19 pandemic is acting as a further accelerant, putting acute pressure on companies’ revenues and cashflow. With overall earnings falling, the value-destructive nature of an underperforming business unit is magnified. New trends and technologies have been established during the pandemic – from remote working to reshaped supply chains – which require incremental investment, adding to competition for capital within corporations. This is driving organizations to pursue asset-light objectives across the value chain, prioritizing those areas that are core to delivering value to their customer base and consistent with their longer-term strategic goals. Those business areas that do not fit these criteria are increasingly becoming targets for divestiture, outsourcing, or closure.

While some believe that major decisions on underperforming or non-core businesses should wait until the path ahead becomes clearer after the pandemic, the counterargument is particularly powerful.

- Firstly, a business that was loss-making prior to the COVID-19 pandemic is unlikely to perform materially better after the pandemic, meaning there is no reason to delay decision-making.

- Secondly, any breathing room afforded by current government support is an opportunity to carry out the strategic thinking required; however, that window of opportunity is temporary and may be short-lived.

This links to the final splash of fuel on the fire. As we start to look beyond the pandemic, lenders, shareholders and indeed governments may no longer be as patient or supportive. As the period of forbearance and economic stimulus ends, the spotlight will swing back toward fundamental business issues and maximizing returns. This urgency was reflected in the 2021 EY Global Corporate Divestment Study, which showed that 89% of activist investors expect to recommend corporate carve-outs of non-core and underperforming assets.

History also shows us the importance of rebalancing portfolios after a major crisis. EY research suggests that there was a 24% outperformance gap between divestors and non-divestors following the 2008 global financial crisis1.

So, what’s stopping global organizations from dealing, once and for all, with their underperforming and non-core businesses in an effort to address these pressing issues?

Chapter 1: Understanding the “problem child” and the way forward

The right answer is often a complex combination of several strategies.

Many businesses delay addressing underperforming or non-core business units for very good reasons – it’s complex, risky and often means overcoming emotional attachments to businesses that haven’t quite worked out. In fact, 78% of respondents in the 2021 EY Global Corporate Divestment Study said they held onto assets too long when they should have divested them, up from 41% five years ago.

Companies must first decide what to do with the “problem child.” Simplistically, this can be a choice between fixing, selling or closing the business. However, the right answer is often a complex combination of these strategies, and the appropriate path requires answering a number of challenging questions, for instance:

- Can the underperforming business unit realistically be fixed to operate profitably and generate positive cash flow?

- If so, how?

- Over what time period?

- And what investment is required?

- Are there viable buyers who would be interested in acquiring the business or parts of it?

- If so, who?

- What measures could be undertaken to improve the attractiveness of the business in order to optimize the sale price and secure the right buyer?

- How would we close the business and how much would that cost?

- What are the risks and how would we minimize impact to the remaining organization?

- How long would it take to fully wind down?

With the uncertainties of fix and sell, close may appear to be the preferred and easiest alternative. However, laying off workers and closing sites is a complex, lengthy and often expensive process — legally, financially and reputationally. The difficult decision to close can also create fractures within an organization as well as with external stakeholders.

Chapter 2: Managing competing demands and interests

Boards must focus on both short- and longer-term pressures.

Put simply, CEOs and Boards already have a lot on their plates, and the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly added to this burden. They must not only focus on prevailing short-term pressures — from changing demand and fractured supply chains to employee safety and remote working — but also steer a path towards an increasingly uncertain future where disruptive forces, particularly around technology, look set to further accelerate.

In such an environment, Boards often need to prioritize their available time to focus on their core businesses. It is therefore unsurprising that CEOs and Boards find it challenging to be fully informed and decisive about their ancillary businesses. So, at a time when most Boards need to take action on their non-core businesses, they often lack the capacity and conviction to do so.

A key priority for Boards is overseeing strategy to create long-term value for the organization as a whole. However, assessing what is in the best interest of the entire enterprise is often complicated by competing objectives and opinions. These are inherent in most global organizations and can be a key to success and a byproduct of the autonomy that modern businesses afford their individual divisions. But they can make addressing issues more complex. Say, for example, a US company with a production facility in Spain wants to shift production elsewhere in Europe. The Spanish unit may feel it is still a viable business, given greater investment and a better internal price for its products and supplies. Other European subsidiaries may feel threatened and rally in support of their colleagues. The Board is left with the unenviable task of deciding on the future direction when there are competing business cases in play.

Chapter 3: Protecting the brand and reputation

There are three key steps Boards should make to move from avoidance to action.

Another potential brake on making tough decisions on the future of non-core businesses is the increasing risk of reputational damage, magnified by a divisive political environment and the ever-rising influence of social media. To give one example; If a US manufacturer decided that its UK operations were no longer viable, it may hesitate to sell or close them for fear that it may draw them into the highly politicized Brexit debate.

While Boards and CEOs need to “be bold,” it is understandable that these challenges and uncertainties can prevent decisive action.

So, how should Boards move from avoidance to action?

Moving from avoidance to action with an underperforming business

1. Boards should take an objective view on options

The ability to step back is critical. Having access to a neutral or objective view, ideally with little or no emotional baggage or internal allegiances, can provide a solid basis to make the right decision about the future of a non-core business area. Creating the resources, either within the organization or by drawing on external support to confirm and document this “independent” perspective can also make the Board’s decision more defensible when it is inevitably scrutinized (by unions, employees, customers, suppliers, press, or other interested stakeholders). This is particularly relevant if the decision results in reducing headcount or shutting down facilities. In these cases, robust preparations are essential to ready the company for the challenges it will likely face including potential litigation and negative publicity

2. Act with speed

Once the decision has been made, speed is of the essence. Firstly, this prevents losses from continuing to mount up. Secondly, once a decision to sell or close has been made, acting quickly is essential to protect the business’ reputation, financial value and employee morale. Achieving that speed means making sure that appropriate resources and expertise are available, whether within the organization or supplemented by specialist external support.

3. Set up the right team

A diverse range of skills are required to address the range of factors that a robust fix, sell or close assessment should consider — from multi-jurisdictional regulations and transaction tax issues to HR, financial reporting and shared services. These critical factors must be quickly addressed to limit potential damage to ongoing operations and the parent company, who will likely be concerned about contract and customer continuity, supply chain resilience and the maintenance of a strong corporate and brand reputation. The number of factors, scale of challenge and the sheer range of risks mean that a dedicated, full-time, experienced team is likely to be required.

Chapter 4: Helping Boards to successfully fix, sell, or close

Global organizations are increasingly taking an interest in addressing non-core business units.

At EY, we’re seeing global organizations take increasing interest in addressing underperforming or non-core business units. It’s an area in which EY teams have supported clients for many years and the examples below — based on recent real-life, anonymized cases — illustrate ways in which Boards and management teams can address obstacles and achieve improved outcomes.

Case studies addressing whether to fix, sell or close an underperforming business

A global automotive original equipment manufacturer (OEM) was reconsidering its manufacturing footprint in light of the shift from internal combustion engines to electric-powered vehicles. This resulted in a Board decision to cease UK production. EY teams were engaged to clarify the rationale, align local and global stakeholders on the direction and help the company prepare for a contentious closure announcement (in a politically charged Brexit environment). Through careful joint planning alongside local management, we avoided negative press from the announcement, concluded employee consultation and facilitated robust closure preparations — all while maintaining high-quality, undisrupted production.

When a US-headquartered global machinery manufacturer decided to close a loss-making German subsidiary during a COVID-19 lockdown, they asked EY teams to help. During a six-week engagement, we explored all options and recommended to sell the downsized business. We then helped manage the wind-down of existing operations, including negotiating staff redundancies and the sale of the unit.

A global healthcare company faced significant capex to refresh its diabetes-related suite of products and services in line with latest market developments. It soon became apparent, however, that a fix was not a viable option and a sell/close was the best route forward. EY teams helped manage the sale and safe transfer of patients to a new provider and wind-down of residual operations globally, all while limiting disruptions to the core business. Proactive stakeholder management and communications to address patients, healthcare providers, employees, regulators, and suppliers was critical to the successful transition and exit.

EY teams helped a leading automotive supplier to carry out a rapid options assessment for an underperforming business unit with operations in Europe, the US and China. Armed with these insights, the management team decided to move forward with a detailed operational turnaround plan, supported by EY professionals, in order to fix the business. As a result, they are now positioned to move the business unit from crisis mode to turnaround status.

The article was first published here.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash.

5.0

5.0